By Peter Fuleky

The economic rebound from the bottom of the Great Recession was less vigorous than post-recession rallies of the past. Notwithstanding some recent pickup of momentum in the US, output growth in developed countries has continued to remain relatively subdued. But should we expect to see any faster growth going forward? Two prominent economists, John Fernald * and Robert Gordon **, point to demographic changes and declining productivity as the limiting factors behind the economy’s lower growth potential.

Most rich countries are facing a handicap due to their stagnant and aging populations. With the ongoing retirement of baby-boomers, the declining labor-force participation rate creates a drag on potential growth. Some of these headwinds have been counterbalanced by growing employment, but faster economic growth would require an unlikely acceleration of labor market improvement. In other words, labor force participation would have to strengthen, or the unemployment rate, which has been falling roughly one percent per year in the US, would have to decline even faster, from 5.6% in December, 2014 to 3.0 percent or below by 2017!

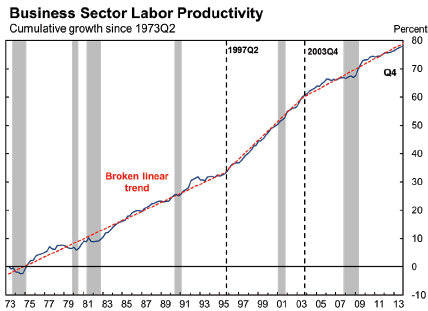

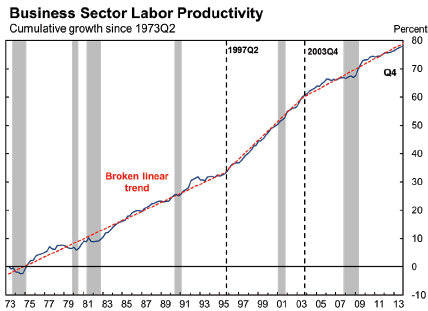

Annual productivity growth, another component of economic expansions, has averaged 0.5% since the recovery started and 1.2% over the past decade in the US. These values are far below the temporary, informationtechnology- fueled pace seen in the mid-1990s and early 2000s. An increase in productivity growth requires an increase in the pace of innovation. So once the main breakthroughs of the IT revolution were fully incorporated into creative processes, they stopped stimulating a further surge in productivity. There were other drivers of exceptional growth earlier in the twentieth century, including electrification, the introduction of the internal combustion engine, and the construction of the Interstate Highway System, but since the 1970s the internet boom was the only episode that elevated productivity growth above 2%.

Slower economic growth has direct consequences for our quality of life. It reduces the chance that today’s generation of young people will double their parents’ standard of living, as has historically occurred across generations. It also increases the burden of public debt by reducing future tax revenues and the size of the economy that finances the debt. The limiting factors mentioned above also have implications for monetary policy. Despite its lackluster growth, the economy may actually be expanding faster than its potential growth rate at present, eventually resulting in upward pressure on wages and the inflation rate and potentially prompting the Fed to raise interest rates sooner rather than later. Finally, slow growth is likely to affect the demand side of the economy in the form of shrinking disposable income and reduced investment.

Demand side proposals to stimulate the economy emphasize the importance of public and private investment. With unfavorable demographic prospects and nominal interest rates close to zero, policy makers also need to fight deflationary expectations. As a response, central banks could raise their inflation targets to 4%, and thereby potentially push real interest rates lower. Supply side policy options for accelerating growth include reforms of the education system, the labour market, and the social welfare system. However, each of these proposals is likely to face political opposition.

Developing countries will feel the effects of reduced demand from rich countries, but many have relatively young populations and rising educational attainment that makes them less vulnerable to the looming growth challenges of the developed world. As a result, future drivers of growth might include India, Latin America, and even Africa. If relatively more global resources flow toward these countries, they may be able to narrow the development gap with the world’s richest countries.

BLOG POSTS ARE PRELIMINARY MATERIALS CIRCULATED TO STIMULATE DISCUSSION AND CRITICAL COMMENT. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED ARE THOSE OF THE INDIVIDUAL AUTHORS. WHILE BLOG POSTS BENEFIT FROM ACTIVE UHERO DISCUSSION, THEY HAVE NOT UNDERGONE FORMAL ACADEMIC PEER REVIEW.