BLOG POSTS ARE PRELIMINARY MATERIALS CIRCULATED TO STIMULATE DISCUSSION AND CRITICAL COMMENT. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED ARE THOSE OF THE INDIVIDUAL AUTHORS. WHILE BLOG POSTS BENEFIT FROM ACTIVE UHERO DISCUSSION, THEY HAVE NOT UNDERGONE FORMAL ACADEMIC PEER REVIEW.

By Ketty A. Loeb and Colin D. Moore

Due to its remote geographic location and extensive coastlines, the State of Hawai‘i is particularly vulnerable to climate change and sea level rise (SLR). While Hawai‘i was among the first states to officially recognize the climate crisis and has played a leading role in combating climate change, Hawai‘i’s lawmakers are still developing plans and policies to address predicted impacts of SLR.

To better understand how Hawai‘i’s elected officials are grappling with SLR, our research team surveyed all currently elected officials in the Hawai‘i State Legislature and the State’s four County Councils between June and September 2023. A total of 32 individuals responded (State Legislature n=18; County Councils n=14) for a combined response rate of 29%. The survey aimed to discover how worried these policymakers are about SLR and what policies they are considering to respond to this slow-moving crisis.

Risk Assessment: How Concerned are Lawmakers about Sea Level Rise?

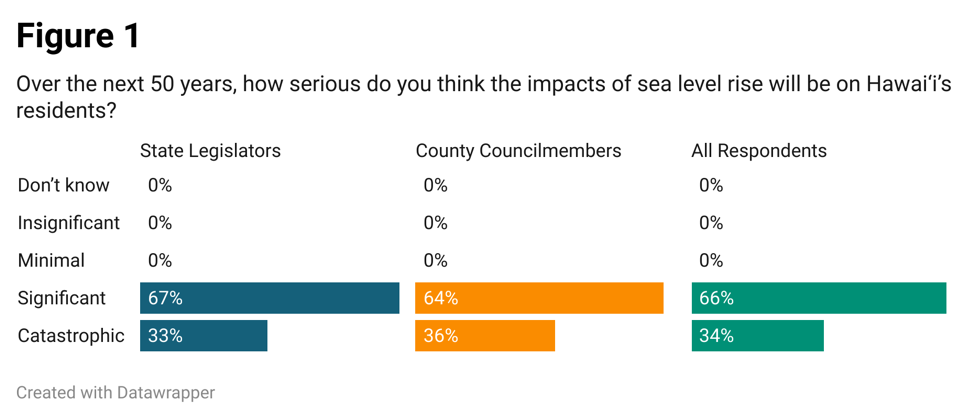

The survey results indicate a universal acknowledgment among respondents that SLR is happening. A slim majority attribute SLR to a mix of human activities and natural processes, while nearly half believe it is solely due to human activities. Overall, policymakers express serious concern about SLR, foreseeing significant or catastrophic effects in Hawai‘i over the next 50 years. As Figure 1 shows, a 34% minority believe impacts on Hawai‘i residents will be “catastrophic,” while 66% think they will be “significant.”

Officials, especially at the county level, feel well informed about SLR, but there are gaps in their knowledge about State and county preparedness and policy options. A majority of County Councilmembers (64%) feel well informed and 36% feel moderately informed. By contrast, the majority (61%) of State Legislators feel only moderately informed while 39% feel well informed.

Respondents overwhelmingly predict serious impacts on Hawai‘i, including frequent flooding, erosion, loss of beaches, and damage to properties and infrastructure. Responding lawmakers are equally confident that Hawai‘i will experience negative socioeconomic impacts, such as damage or loss of coastal properties (100%), increases in insurance premiums (97%), disruption or losses in major tourism/resort areas (88%), loss of important cultural sites and practices (97%), public health issues related to environmental contaminants (88%), forced relocation of communities (82%), insurance companies ending coverage due to high risk (78%), and increased socioeconomic inequality (72%).

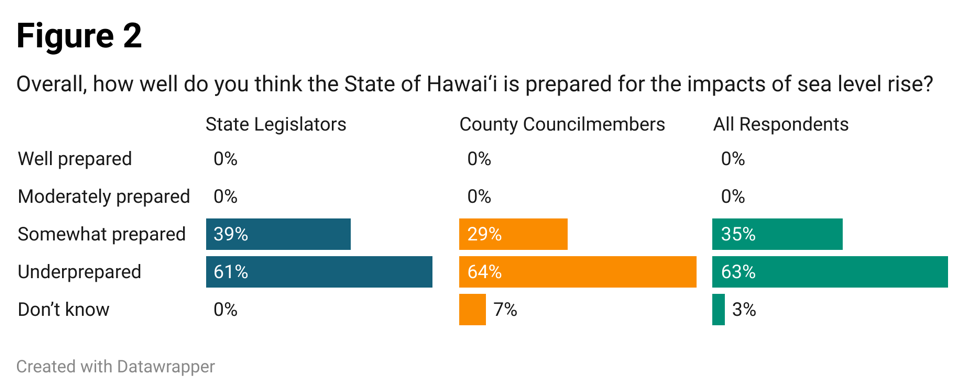

Perhaps most troubling, no respondents find the State well-prepared for the impacts of SLR. As Figure 2 demonstrates, most lawmakers (63%) believe Hawai‘i is underprepared, while 35% think Hawai‘i is only somewhat prepared.

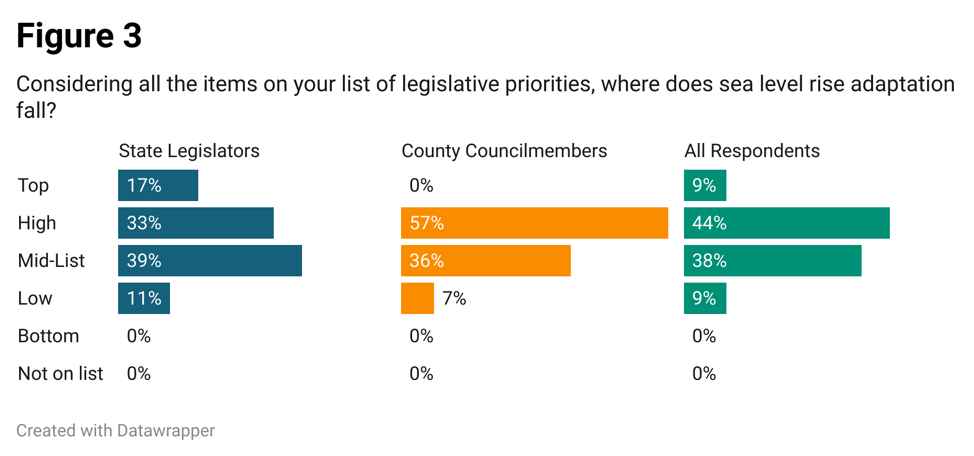

Despite the high level of concern and general agreement that Hawai‘i is unprepared, Figure 3 shows that SLR is not a top priority among Hawaiʻi’s policymakers. Only 9% of total respondents rank SLR as a top priority, while 44% percent place it high on their list and 35% place it mid-list. Given the severity of perceived risks, it is notable that the issue does not rank higher, especially because our sample likely includes policymakers who are particularly concerned about SLR.

Policy Preferences: What Adaptation Strategies do Lawmakers Support?

Strong support is evident for nature-based solutions, such as restoring living shorelines and safeguarding critical infrastructure (94% of respondents support both strategies). Regulatory measures, including zoning and setback laws (91% support), also receive considerable backing, reflecting a preference to manage development in coastal areas. Other policy measures that command strong majority support include adopting permitting tools that incentivize removal or relocation of SLR-damaged structures (75% support), while 65% favor creating mandates to remove seawalls where no beach is left, and 60% support using transfer of development rights (TDR) to enable relocation for coastal owners.

While policymakers indicate a wide interest in policy responses, some policy options elicit far less enthusiasm. Respondents were largely opposed to constructing sea walls and other structural barriers along the shoreline. Only 28% express some support for this approach, while 53% of respondents indicate some or strong opposition. Respondents were also skeptical about government-financed buyouts of private coastal properties. While 22% support this policy, 25% are somewhat oppose and 22% are strongly opposed. Indeed, responding lawmakers overwhelmingly judge this to be the least attractive policy solution among the set of “managed retreat” SLR adaptation measures.

What are the Major Obstacles to Progress?

Regarding obstacles to policy progress, our survey results show that lawmakers are particularly concerned about funding and staff support for the implementation of SLR adaptation strategies, and coordination among county agencies and State government. More specifically, elected officials point to the lack of funding to implement a plan (78%), insufficient coordination among agencies and stakeholders (72%), and the need for more staffing resources to analyze information (34%).

Recommendations

Based on these survey findings, we offer the following recommendations to individuals and agencies working on SLR adaptation planning in Hawaiʻi.

- Implement Policies that Lawmakers Already Support. Respondents largely agree on revising permitting and building codes to promote resilient construction practices and elevate buildings in vulnerable areas. There is also a broad consensus on enforcing recently updated codes and coastal regulations and on using nature-based solutions to SLR, such as restoring and promoting living shorelines. Additionally, there is strong support for using public funds for the purchase of coastal lands to maintain and restore natural areas.

- Enhance Policy Coordination. Survey respondents believe limited coordination among agencies and stakeholders is a significant obstacle to addressing SLR. To overcome this obstacle, policymakers could create new comprehensive and collaborative governance structures and strategies to address SLR, which include federal, State, and county agencies, as well as non-profit organizations, corporations, and community stakeholders.

- Address Policy Knowledge Gaps and Lack of Analytical Capacity. Respondents say they need more information about the available policy options and successful responses in other jurisdictions. To close this knowledge gap, experts and researchers should consider how they can better communicate with policymakers about effective SLR policies and how they can be adapted to the needs of Hawai‘i. Lawmakers also indicate that they need more staff to help them make sense of the data and policy response options for SLR adaptation. This lack of capacity could be managed by increasing the number of research and planning staff at key agencies, particularly at the State’s Office of Planning and Sustainable Development and the Office of Conservation and Coastal Lands, and at the various climate change and sustainability offices across the four counties.

- Prioritize Planning and Funding for SLR Adaptation. Hawai‘i’s leaders cite a lack of funding for planning and implementation as a significant obstacle to SLR adaptation. Although national political dynamics largely determine federal funding, Hawai‘i should be prepared to capitalize on significant federal investments, such as the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). Hawai‘i’s leaders could also consider new revenue streams for funding large- and small-scale adaptation projects, and work to overhaul State and county procurement systems. Finally, policymakers should continue to explore public-private partnerships with corporations and nonprofits to ensure access to the best technology and community engagement practices.

Conclusion

Overall, these survey results reveal a gap between perception and policy action regarding SLR in Hawai‘i, which is both pronounced and perplexing. Despite the overwhelming consensus among Hawai‘i’s policymakers on the imminent threats posed by SLR and the State’s lack of preparedness, it is not considered a top policy priority. Indeed, few policy recommendations that explicitly involve public expenditures are given much support. Although Hawai‘i has made noteworthy strides in establishing foundational legal frameworks and planning tools for SLR, the findings of this survey indicate a clear opportunity for policymakers to bridge the divide between awareness and action. The stakes are undeniably high, and lawmakers can still meet this challenge through coordinated and rapid action.