BLOG POSTS ARE PRELIMINARY MATERIALS CIRCULATED TO STIMULATE DISCUSSION AND CRITICAL COMMENT. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED ARE THOSE OF THE INDIVIDUAL AUTHORS. WHILE BLOG POSTS BENEFIT FROM ACTIVE UHERO DISCUSSION, THEY HAVE NOT UNDERGONE FORMAL ACADEMIC PEER REVIEW.

By James Mak

A recent report—Total State and Local Business Taxes—published by Ernst & Young LLP, State Tax Research Institute, and Council on State Taxation presents detailed state-by-state estimates of state and local taxes paid by businesses in Fiscal Year 2021. The report (hereafter referred to as the Ernst & Young report) is in its 20th year of publication. State and local business taxes are taxes that businesses are legally required to pay to their state and local governments.1 The estimates of business taxes are based on tax collection data published by the U.S. Census Bureau (Annual Survey of State and Local Government Finances). Researchers separated the Census Bureau tax collection data between revenues which are attributable to businesses and the rest to “households.” This essay examines where Hawai’i stands on business taxation in relation to the other 49 states and the District of Columbia (D.C.) and explains what the report’s estimates mean and don’t mean.

In FY21, firms doing business in Hawai’i paid $4.5 billion in Hawai’i state and local (county) taxes, accounting for 38.1% of the $11.8 billion total tax revenues collected by Hawai’i’s state and county governments from all taxpayers. The 38.1% figure is below the national average of 43.6%. Hawai’i’s county governments rely relatively more heavily on business activity taxation than the State—53.6% of total tax revenues collected by the counties versus $31.5% for the State. For the U.S. as a whole, local governments in 35 of the 50 states are also more dependent on tax revenues collected from businesses than their state government.

The business share of state and local tax collections varies widely by state, reflecting the states’ diverse tax structures. Seven states had business tax shares that were lower than Hawai’i’s. North Dakota had the highest business tax share at 70.9%, while Maryland had the lowest business tax share (31.3%). The share of taxes collected from businesses tends to be greater in states that depend heavily on severance taxes (i.e. taxes levied on the extraction of natural resources such as oil and natural gas) and in states that don’t impose an individual income tax.

For Hawai’i businesses, property taxes ($1.5 billion) and general sales taxes on the purchases of intermediate inputs and capital expenditures ($1.3 billion) were at the top of their state and local tax liabilities; the corporate income tax contributed a mere $200 million to State and county tax coffers in FY21. Likewise, among all fifty states and the District of Columbia (D.C.), property taxes ($368.8 billion), and general sales taxes on intermediate and capital purchases ($194.5 billion) comprised the top two sources of total state and local business tax collections ($951.5 billion), well above corporate income tax collections ($111.0 billion).

To compare each state’s effort to raise taxes, the Ernst & Young report calculated an effective business tax rate (TEBTR) for each state. TEBTR is derived by dividing the sum of total (state and local) tax revenues collected from businesses by the relevant tax base. A proxy for the relevant tax base is the private sector share of gross state product (GSP) which measures the total value of a state’s annual output of goods and services (net of intermediate inputs) produced by the private sector. Thus, a state’s effective business tax rate = business tax collections by state and local governments/ private sector GSP.

In FY21, the average effective business tax rate across all states and D.C. was 4.9%. Hawai’i’s effective business tax rate was 6.6%. The state with the highest effective business tax rate was New Mexico (8.6%), while North Carolina (3.6%) had the lowest effective business tax rate. Hawai’i ranked 7th among the 50 states and the District of Columbia, although the Ernst & Young report doesn’t rank each state’s tax effort.

We also checked the FY2019 report that would have preceded the Covid-19 pandemic. It showed that in FY19 Hawai’i’s effective business tax rate was 5.6% and the average effective business effective tax rate for the U.S. was 4.5%. Nine states had effective business tax rates that were higher than Hawai’i’s. The state with the highest effective business tax rate was North Dakota (10%), while North Carolina and Michigan had the lowest effective business tax rates (3.3%).

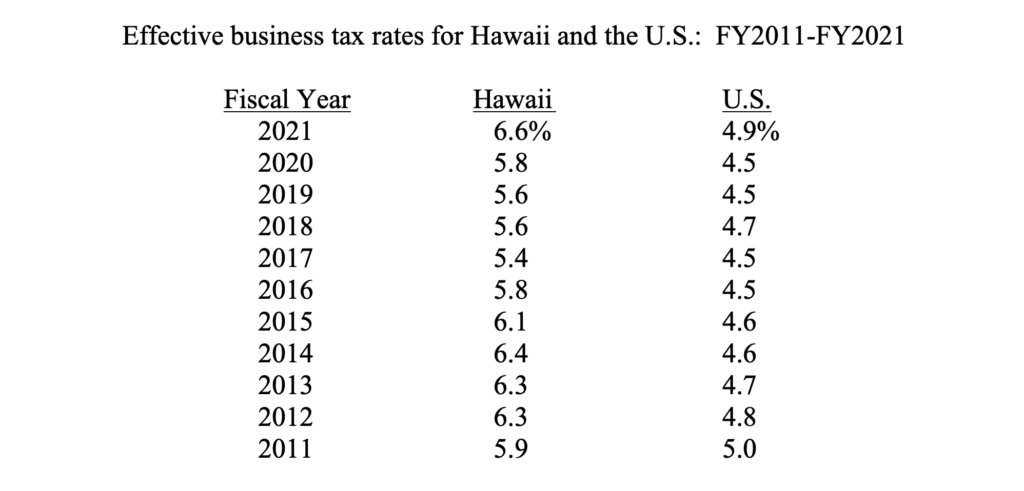

The following table displays effective business tax rates for Hawai’i and for the U.S. between FY2011 and FY2021.

Source: Ernst & Young LLP, Council on State Taxation, and State Tax Research Institute, Total State and Local Business Taxes, various years.

Compared with other states, Hawai’i’s high TEBTR suggests that Hawai’i taxes its businesses more heavily than most other states. That conclusion would be premature. As the Ernst & Young report notes, the TEBTR does not take into account that some of the taxes paid by businesses are not actually paid by businesses because they are passed on to consumers. The person who writes the check to the tax department to comply with his business tax obligations may not be the person who ultimately bears the “burden” of the tax when the tax is subsequently passed on (as higher after-tax prices) to his customers. In the language of economists, TEBTR doesn’t take into account the economic “incidence” of the tax (as opposed to its legal incidence). Studies have not established firm estimates of who ultimately pays all of these taxes.

Economists William Oakland and William Tesla at the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago argue that since only individuals as consumers, workers, entrepreneurs or suppliers of land and capital can “bear the burden” of taxes, it isn’t very useful to talk about tax incidence in the context of business taxation. They argue that “the primary basis for general business taxation is to recover the costs of government services rendered to the business community.”2 The cost recovery proposition is attractive because it is grounded in the benefits principle of taxation.3

Do state and local governments around the country recover through business taxes the cost of public services they provide to businesses? The Ernst & Young report attempts to answer that question by computing a “business tax-to-benefit ratio” for each state. The ratio is calculated by “dividing the amount of business taxes in each state by the estimated amount of government expenditures that benefits businesses.” It is not an easy calculation as many government expenditures benefit both businesses and households and assignment of costs—which may require bold assumptions—is necessary. A good example is education.

By far, the largest category of state and local government spending is on education. Businesses value an educated workforce. So, it is undeniable that businesses benefit from government spending on education, but there is uncertainty over how much. Since estimates of the business tax-to-benefit ratios are sensitive to how education expenditures are allocated between businesses and households, for the Ernst & Young report, researchers calculated business tax-to-benefit ratios assuming that the share of government spending on education that benefits businesses is either 0%, 25%, or 50%. Zero percent is clearly unreasonable. Focusing on the 25% benefit assumption, in FY21 Hawai’i’s business tax-to-benefit ratio was 1.1, meaning that businesses in Hawai’i paid $1.10 in state and county taxes to receive in return $1 in government spending that benefits them. The national average ratio was 1.5. The state with the highest tax-benefit ratio was New Hampshire (2.6) while Alaska was the only state with a tax-benefit ratio below 1.0 (0.8).

Employing the 50% benefit assumption, Hawai’i’s tax-to-benefit ratio fell below 1.0 (0.9), meaning that Hawai’i’s businesses paid less than one dollar in state and local taxes in order to receive one dollar of government spending that benefits them. If the 50% benefit assumption is correct, firms doing business in Hawai’i received a tax subsidy. Ten other states (plus the District of Columbia) had tax-benefit ratios below 1.0. The 50% education benefit assumption is also unreasonable.

Despite the wide range of education benefit assumptions (from 0% to 50%), Hawai’i’s tax-to-benefit ratio is in the neighborhood of 1.0. That suggests that Hawai’i’s state and county governments (collectively) seem to be doing a reasonable job of getting businesses to pay their appropriate (i.e. not too much or too little) share of the cost of government services. If cost recovery is the main purpose of business taxation, Hawai’i’s current (general) business tax structure appears not to be in desperate need of major reform. That said, more research should be done on the government expenditure side to allow more precise assignment of expenditures that benefit businesses versus households.

A note of caution: the Ernst & Young’s business tax-to benefit ratios don’t inform whether or not taxpayers get their money’s worth. The “benefit” in the tax-to-benefit calculations is the amount the government spends to provide services intended to benefit businesses and not how much benefit businesses actually derive from the expenditures. Taxpayer dollars may be spent effectively or ineffectively. For example, in the 2022 National Community Survey of Honolulu, 385 Honolulu residents were asked to rate “the value of services for the taxes paid to Honolulu”; only 24% of the respondents gave a positive response. The percentage of Honolulu respondents who gave a positive response was much lower than in other communities across the country. Respondents were not down on all government services; 63% of the respondents rated garbage collection as excellent or good while only 8% rated street repair positively.

Finally, how heavily a state taxes its businesses is widely believed to affect each state’s economic competitiveness. The Ernst & Young report correctly warns that TEBTR is not a comprehensive measure of a state’s economic competitiveness.

There are many factors that determine a state’s economic competitiveness. Besides the tax structure, the quality of the local labor force, proximity to higher education institutions, level of public services, proximity to buyers and suppliers, etc. may be even more important to businesses. In a study prepared for the Connecticut Tax Study Panel to ascertain what changes may improve Connecticut’s chances of fostering greater economic growth, Syracuse University economist Michael Wasylenko concluded that businesses locate to the Northeast for its workforce and largely go to other regions of the country for the workforce in those regions. Competition in taxes and public service provision have the most effect on business expansion and location when competition is between nearby states and not when competition is across different regions of the country.

The Ernst & Young report does a fair job of describing the diversity of taxes levied by state and local governments in the U.S. and who (and how much)—businesses or households—are legally obligated to pay them. It is not a report with strong policy prescriptions on how to improve a state’s business climate.

Acknowledgements: I thank Bob Ebel and Bill Fox for helpful comments on earlier versions of this essay. Remaining errors, if any, are mine.

References & Footnotes

1 Business taxes include property taxes paid by businesses; sales and excise taxes on intermediate inputs and capital expenditures (i.e. sales taxes on final goods consumed by households are not included); corporate income tax, gross receipts tax, franchise tax and license taxes on businesses and corporations; share of individual income taxes paid by owners of non-corporate businesses; unemployment insurance taxes, and all other state taxes that are the statutory liability of business taxpayers.

2 William H. Oakland and William A. Testa, “State-local business taxation and the benefits principle,” Economic Perspectives, Jan/Feb, 1996, Vol. 20 Issue 1. There are other reasons to tax businesses such as taxes to mitigate environmental damage or to capture economic rents.

3 Indeed, if business taxation is about cost recovery, the term “tax burden” should be changed to “tax price” as taxes paid for government services are not a “burden” but the prices of those public services.