By Zoe Hastings, Mahealani Botelho, and Leah Bremer 1

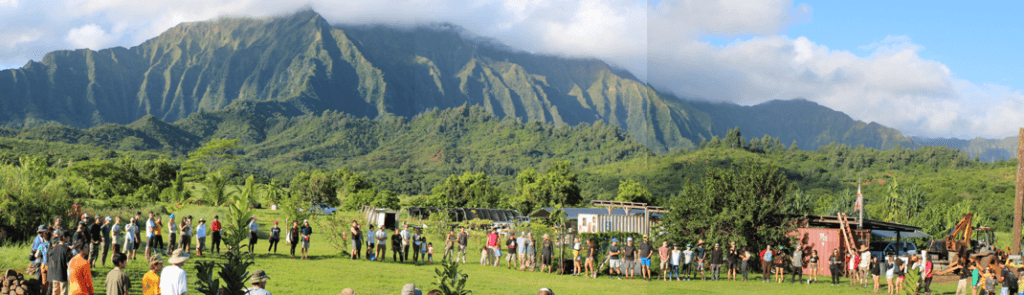

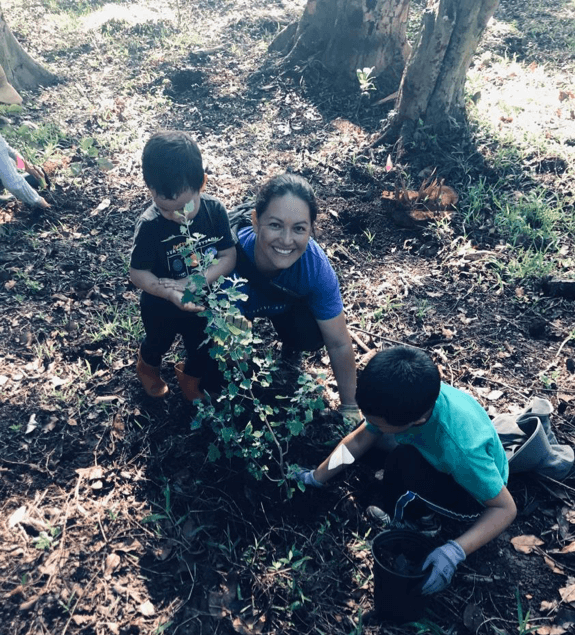

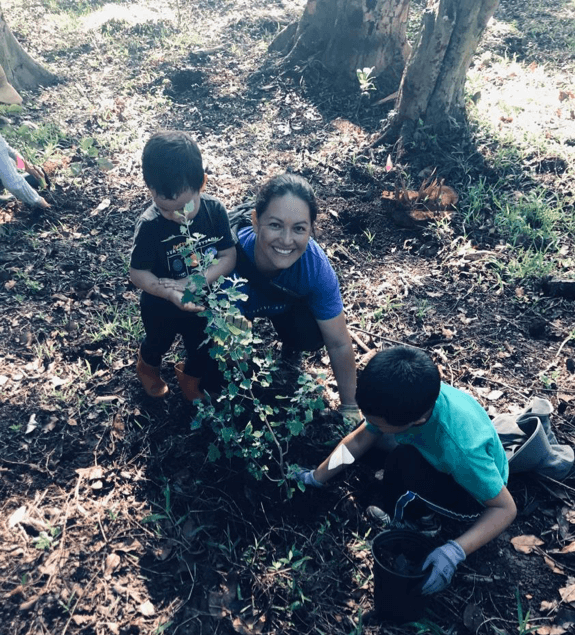

“I ola ʽoe, i ola mākou nei.” A community member recites the pule (blessing), “my life is dependent on yours, your life is dependent on mine”, to a native aʽaʽliʽi shrub as she gently tucks them into the ground. The side of the ridge is a sea of colorful flags marking holes where nearly 200 energetic volunteers ages one through 85 plant a variety of native and other culturally valued trees and shrubs. Here the goal of restoration is not just the final outcome, but the process of bringing community together and restoring cultural connection to place.

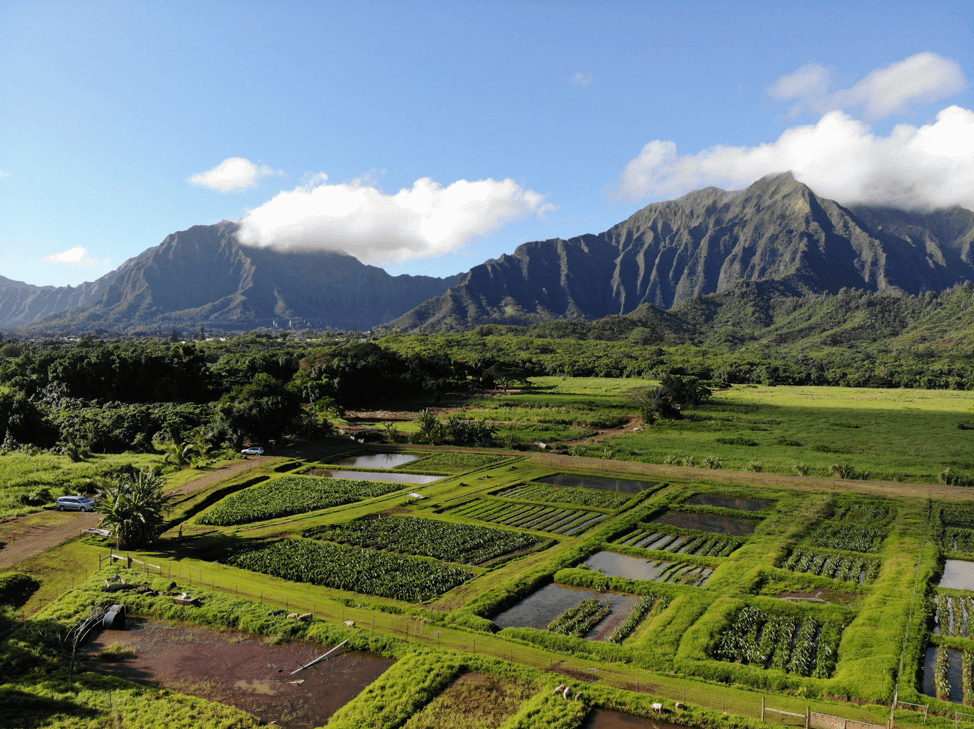

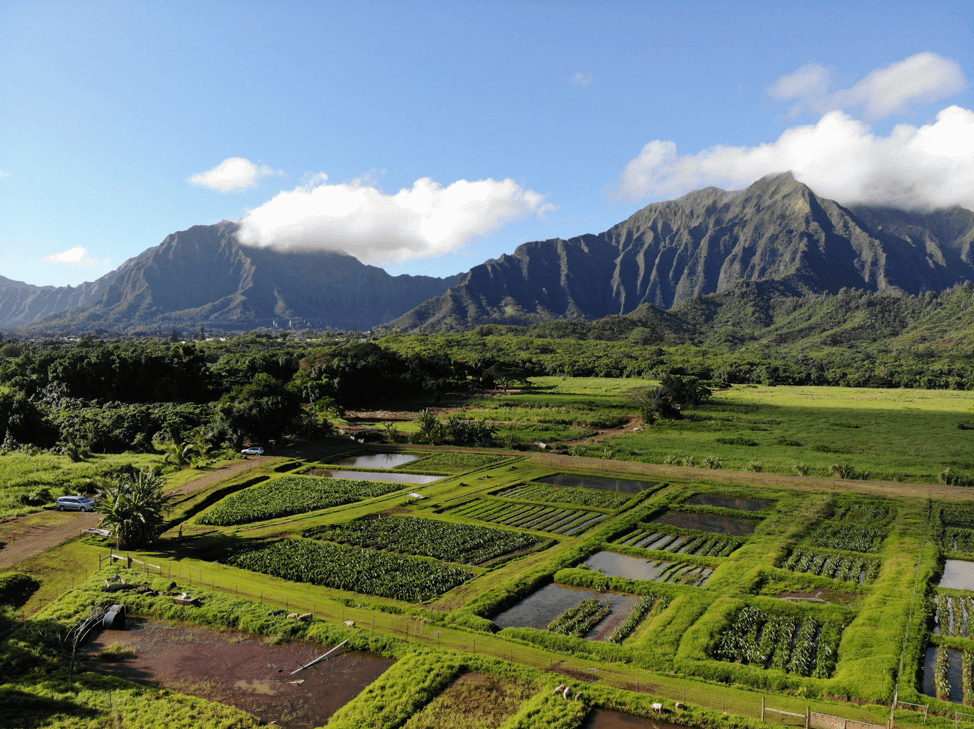

Puʽulani stretches like a finger into the Heʽeia wetland, a ridge rising above the alluvial plane. Restoring the traditional name, heavenly or spiritual ridge, and planting culturally important species are the first steps in the process of reconnecting people with this puʽu. Staff at the local nonprofit Kākoʽo ʽŌiwi (kakoooiwi.org) are working to restore ecological and cultural vitality to over 400 acres here.

Many native, culturally important plants are only found in remnant forests high up in the mountains. There, it can take significant time and energy to reach them, meaning many people, especially keiki and kupuna, do not have the opportunity to interact with the plants. The plants at Puʽulani are only a short walk or drive from Kākoʽo ʽŌiwi’s entrance past an extensive network of loʽi. As one volunteer reflected, “it is uplifting to see so many people come together from diverse walks of life.”

“I’ve done a lot of restoration, but I have never seen ohiʽa next to ʽawa and ʻāweoweo. Why did you put them together?” a volunteer asked. The goal of many restoration projects is to re-establish native forest as it was pre-European contact. Instead, at Puʽulani we are bringing together plants that help us achieve both biological and cultural (biocultural) restoration goals such as strengthening community connectedness to place, producing lei making materials, medicine, and food, sequestering carbon, and reducing erosion in a land use system called agroforestry.

Agroforestry is the intentional combination of trees with crops and/or livestock. At first glance, a multi-story agroforest may look similar to a native forest, but the mix of plants is often different from what might grow together without human intervention and may include native and introduced species.

Agroforests were widespread in Hawaiʽi prior to European contact, yet relatively few remain today. At Puʽulani, we are interested in understanding how we can adapt traditional agroforest models to a contemporary context, designing systems that are resilient into the future.

To do this, we set up a controlled experiment testing two different restoration approaches, or species mixes. The hillside is divided into ten plots in which five plots have one set of species and the other five have a different group of species. In the plots we are tracking plant growth and survival as well as indicators of multiple ecosystem services such as soil carbon, erosion, and surveys of visitors who participate in the project. The project is a collaborative effort led by Kākoʽo ʽŌiwi’s staff and UH researchers from Botany, UHERO’s Project Environment, the Water Resources Research Center, and NREM.

By documenting benefits and costs of our two approaches over time, we hope to provide land managers, farm owners, and others with information that can use to make decisions about adopting agroforestry on their land.

While we are still finishing the initial agroforestry planting at Puʽulani, the keiki plants are already creating space for community to learn and feel connected. As one person expressed about their experience, “I understood the energy exchange of giving back to the land, I felt a part of the community taking care of the land that takes care of us.”

Want to get involved? Join us at Kākoʽo ʽŌiwi every second Saturday of the month to care for the agroforest and loʽi.

BLOG POSTS ARE PRELIMINARY MATERIALS CIRCULATED TO STIMULATE DISCUSSION AND CRITICAL COMMENT. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED ARE THOSE OF THE INDIVIDUAL AUTHORS. WHILE BLOG POSTS BENEFIT FROM ACTIVE UHERO DISCUSSION, THEY HAVE NOT UNDERGONE FORMAL ACADEMIC PEER REVIEW.

[1] Zoe Hastings is a PhD student and NSF Graduate Research Fellow interested in collaborative biocultural restoration of agroecological systems. She works closely with Mahealani Botelho and others at Kākoʻo ‘Ōiwi and the UH research team to collaboratively design the restoration and research process at Puʻulani. Leah Bremer is an Assistant Specialist with UHERO’s Project Environment and the Water Resources Research Center and a project PI alongside Tamara Ticktin and Clay Trauernicht. Many others have contributed to this effort including Kanekoa Kukea-Shultz, Nick Reppun, and all the Kākoʻo ʻŌiwi staff, as well as Angel Melone, a graduate student helping with many dimensions of the project. We thank our funders, including the United States Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service, Conservation Innovation Grants program (# NR1892510002G003), the College of Social Sciences Research Support Award, and the Heʻeia National Estuarine Research Reserve.