By Leah Bremer

“Want to carry one up?” the natural resource management team with Limahuli gardens in Haʻēna, Kauaʻi asks us as they hand out potted endangered plant seedlings before our hike up the trail toward one of their native forest restoration areas. We arrive 30 minutes later to the first restoration plot and are amazed to see an oasis of diverse native plants in a broader sea of mostly non-native forest. Restoration like this provides many benefits including biodiversity, cultural value, watershed protection, but it can also be expensive. Limahuli gardens, like so many natural resource managers around the State, face decisions around where and how to invest limited conservation resources. In an effort to cost-effectively restore a larger area of forest that provides a suite of ecological and cultural (ie biocultural) benefits, managers at Limahuli are pioneering careful consideration of multiple restoration strategies, including hybrid restoration with native and culturally useful non-invasive introduced species.

On the other side of the Hawaiian Islands, we have the rare opportunity to spend time in the Kaʻūpūlehu dry forest restoration project in North Kona, Hawaiʻi Island, a highly successful community-based effort to restore the most threatened ecosystem in the world. Many of the community members who work here are from cattle ranching families. They see tremendous value in mixed use landscapes including native forest and pasturelands, but worry about encroaching urban development. In this context, landowners across the State, including Kamehameha Schools, face decisions about the future of pasturelands, including the right mix of continued pasture, forest restoration and other land use options like coffee or restoring to agroforestry (a once prominent land use in the region).

Real-world decision contexts like these have spurred a growing body of research striving to shine light on the ways that land management decisions influence societal well-being. Huge strides have been made to operationalize inclusion of the ‘value’ of land into decision making. Yet, this body of work largely remains siloed between those focusing on the biophysical and monetary values and those focusing more broadly on socio-cultural values. This division precludes a pluralistic set of values being included in decision-making in a meaningful way.

Over the past 3 years, UHERO, through an NSF Coastal SEES project – “Linking local ecological knowledge, ecosystem services, and community resilience to environmental and climate change in Pacific Islands”—has been part of a transdisciplinary team of researchers who have worked closely with landowners and communities in several study sites, including Haʻēna and Kaʻūpūlehu to bridge this divide.

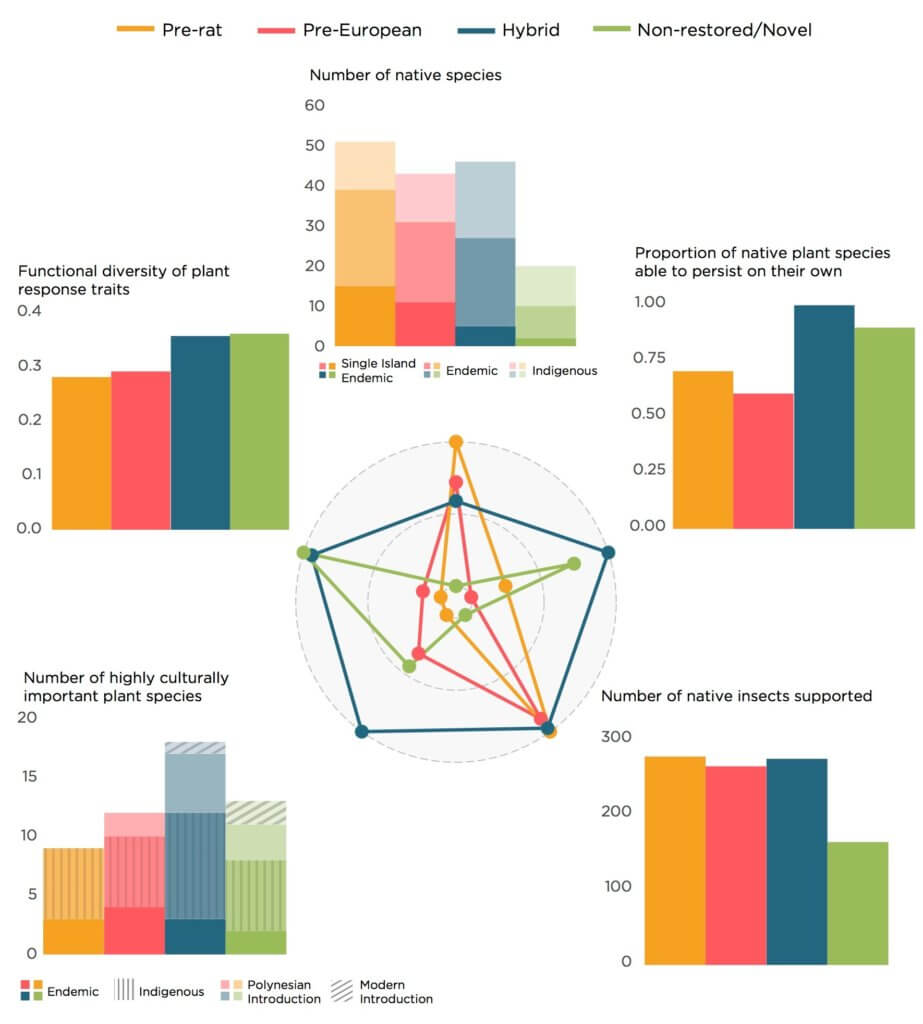

In Haʻēna we worked alongside Limahuli reserve manager, Kawika Winter and his staff, to explore the costs and benefits of 3 restoration strategies: 1) restore to a state before rats were introduced (pre-rat); 2) restore to a pre-European state; and 3) restore using a mix of native and culturally useful non-invasive introduced species (hybrid scenario). Within each scenario, we evaluated the restoration costs alongside the benefits in terms of native and endemic species of plants restored, resilience (measured by functional diversity), and cultural value of plants restored. Cultural value was assessed based on a framework of past and current use based on community workshops and the long-term experience of managers working in the area. Interestingly, we found that the hybrid scenario provides important ecological benefits in terms of restoring a resilient mix of native species while also supporting a variety of culturally useful plants at a cost much lower than the other restoration strategies. While conservation of endangered species requires additional strategies, hybrid restoration offers a cost-effective way of scaling up restoration that can also provide important cultural and community benefits.

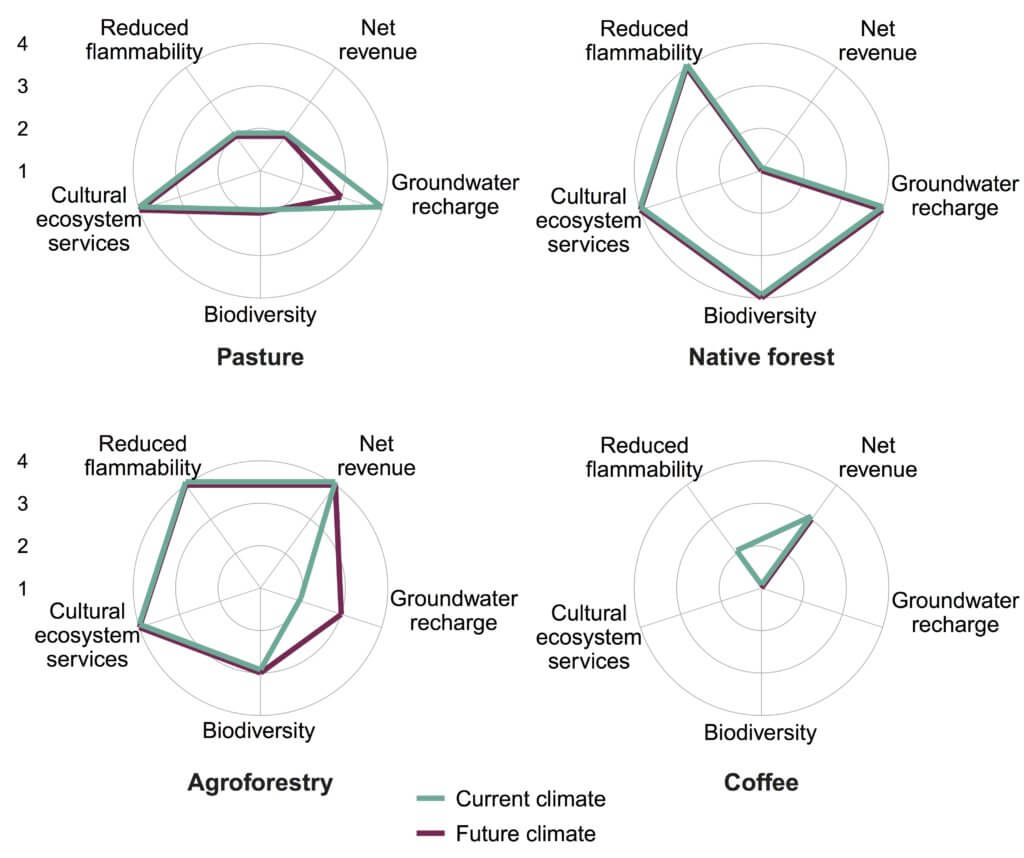

In Kaʻūpūlehu, we worked alongside Kamehameha Schools and the Kaʻūpūlehu community to evaluate potential futures of pastureland. We considered the management costs and environmental (biodiversity, groundwater recharge, fire risk), cultural, and economic outcomes of four future land use scenarios on a large cattle ranch: 1) retain pasture; 2) restore native forest; 3) restore agroforest; and 4) convert to coffee. Unsurprisingly we found that no one land use was the best on all metrics assessed, and that cultural value (assessed using participatory, deliberative methods and an indigenous cultural values framework) was very high in all land uses except for coffee (which is not an important land use in the immediate area). Similar to Haʻēna, we found that the agroforestry scenario (a hybrid forest) offered the greatest potential in terms of multiple benefits, including economic return. Yet, it is pasture which currently provides some of the highest cultural value in terms of local knowledge and cultural connection to place. Rather than providing clear answers to Kamehameha Schools about the “best” way forward, our research provided a way to bring multiple values, including cultural and environmental values, to the table in a concrete way.

Integrating and including diverse values into decision-making is challenging, but critically needed around the world. We see no better place than Hawaiʻi to continue to work with on-the-ground managers to move this forward to contribute to more sustainable and resilient decisions. As an extension of our work in Kaʻūpūlehu and Haʻēna, we are now collaborating with a local non-profit Kakōʻo ʻŌiwi in Heʻeia Oʻahu to consider the multiple benefits of loʻi restoration through time. More to come!

Note: The NSF Coastal SEES project Principal Investigators were: Tamara Ticktin (UHM Botany), Kim Burnett (UHERO), Alan Friedlander (UHM Biology and National Geographic), Tom Giambelluca (UHM Geography), Stacy Jupiter (Wildlife Conservation Society -Fiji), Mehana Vaughan (UHM NREM), Kawika Winter (National Tropical Botanical Garden), Lisa Mandle (Natural Capital Project, Stanford), and Heather McMillen (NREM). Special thanks also to project researchers and graduate students who carried out much of this work, including Puaʻala Pascua, Shimona Quazi, Natalie Kurashima, and Christopher Wada. Finally, we are grateful to our community and landowner partners in Kaʻūpūlehu and Haʻēna who made this project possible.

BLOG POSTS ARE PRELIMINARY MATERIALS CIRCULATED TO STIMULATE DISCUSSION AND CRITICAL COMMENT. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED ARE THOSE OF THE INDIVIDUAL AUTHORS. WHILE BLOG POSTS BENEFIT FROM ACTIVE UHERO DISCUSSION, THEY HAVE NOT UNDERGONE FORMAL ACADEMIC PEER REVIEW.