The WEER Student Blog Series features student reviews of presentations from UHERO’s Workshop on Energy and Environmental Policy

Abstract: Conventional wisdom suggests that oil price increases have a negative effect on the output of oil-importing countries. This is grounded in the experience of the US between 1940s and late 1980s where recessions are generally preceded by oil price increases. In this paper, we evaluate the impact of oil price shocks on the Philippines–– a developing country and a net oil-importing economy. Following Kilian’s (2008) structural decomposition of real oil price change, we find indications that the recent oil price decline may have lowered the Philippine economy’s output growth, potentially due to the economy’s reliance on remittances from abroad and the export market.

– Arlan Brucal and Michael Abrigo, University of Hawaii Economic Research Organization (UHERO), East West Center, September 12, 2016.

Review by Trevor Fitzpatrick

Since the beginning of 2016, oil prices have hovered around $30 to $50 a barrel. These current prices are about a third of the 2008 peak crude oil price of $145 per barrel. The recent significant drop in oil prices are the greatest we have seen since the 1980s. Like many other price fluctuations in goods, the recent drop in oil prices have benefited some more than others. Conventional wisdom suggests that low oil prices will benefit oil consumers while oil exporters will suffer. As the case may be, the effect of low oil prices is not that simple.

On September 12, Arlan Brucal highlighted the importance of looking at the causes of recent oil price changes, and their direct and indirect effect to an economy through international trade and factor mobility. Focusing on the Philippine’s economy as a test case, Arlan finds an indication that the recent oil price drop may have slowed down the growth of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) by 5.5 percent. This seemingly counterintuitive result is largely due to the fact that the Philippine economy is heavily reliant on service exports, a component of the national output that suffered heavily from the recent oil price drop. Demand for crude oil has not recovered from the 2014 slump, and still cripples oil-exporting economies, which host most of the overseas Filipino workers (OFWs). Over the past decade, remittances received by the Philippines from abroad account for about 15% of the country’s GDP. The share of remittances to Philippines’ total output is significantly higher than India and China – the two biggest recipients of remittances in 2014 – and much higher than world averages.

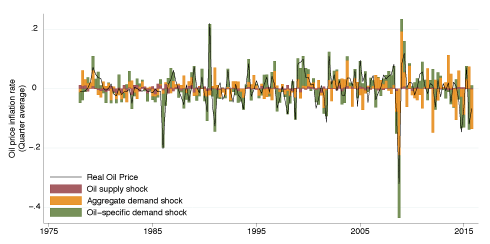

Arlan and Mike’s study employs Kilian’s (2008) vector autoregression (VAR), which decomposes oil price shocks into supply shocks, aggregate demand shocks and oil-specific demand shocks. Supply shocks are unanticipated changes in the global crude oil supply. These supply shocks could emanate from exogenous geopolitical conflicts, discovery or new resources, or technology (i.e. fracking). Aggregate demand shocks are unanticipated changes in real economic activity, which includes economic booms in China or economic recessions that reduce the demand for industrial commodities including crude oil. Oil-specific demand shocks are changes in the demand for crude oil that are not related to aggregate demand shocks. These shocks include precautionary demand shocks associated with the future oil demand-supply conditions. An example of which would be a sudden drop in the price of oil because of the looming conflict in the Persian Gulf in the early 2000s. The study finds indications that the recent drop in oil prices are driven by a combination of both aggregate demand and oil-specific demand shocks. These findings are in contrast to the popular view that cheap oil is due to an oil oversupply caused by the surge in US oil production (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Historical Decomposition of World Crude Oil Price Changes

Source: Brucal and Abrigo (2016)

While the results appear to be quite convincing, their external validity is yet to be established. Indonesia presents a potentially good comparison example for this study. Indonesia and the Philippines share many commonalities: multicultural/ethnic, developing countries, nations that consists of many islands, exportation of laborers to many oil producing countries, etc. Does Indonesia have a similar pattern of remittances from overseas workers in oil producing countries, and do cheap oil prices negatively affect these remittances to Indonesia like they do in the Philippines? The fact that Indonesia is an exporter of oil could make the comparison difficult, but there are recent arguments and evidence that Indonesia’s oil production is starting to decline and that it is starting to consume more oil than it is producing. While Indonesia presents one interesting case to compare the Philippines with, further research could be expanded to include a number of countries with a wide range of dependence on remittances, which might help to establish if remittances is indeed a major mechanism.

Additionally, it was pointed out that the Filipino diaspora in the US was not accounted for, or that the US-Filipino diaspora did not make up a noticeable population and source of remittance as some the other overseas Filipino populations. One would assume that the US Filipino diaspora would still be a large population. Taking into account that cheap oil prices have been associated with economic booms in the US, we could possibly hypothesize that remittances from Filipinos in the US would increase. Could this US-Filipino remittance recover the losses felt from the loss of petro-dollars and remittances from Filipinos that work in oil producing countries? This could be another aspect to consider.

The negative impacts that Arlan’s findings could have are possibly reflected in the lack of sophistication of the Philippines workforce. Continued export of unskilled laborers to oil producing countries and the reliance on their income partly being shifted back to the Philippines is potentially holding its economy back. However, if the Philippines is labor abundant and capital poor, the Philippines may be better off by exporting workers to labor deprived countries. Perhaps further development of the workforce could help decrease some of the reliance on service jobs in oil producing countries. Further education and development in human capital can certainly help. The Philippines could also encourage more foreign direct investments as well although negative impacts particularly on natural environment would have to be monitored.

Arlan and Mike’s study is part of a bigger project that studies the impact of oil price-related shocks to developing countries. Most of the current literature has focused on the more advanced economies of the world like the US. Hopefully, Arlan and Mike’s study will help fill the void in the literature on the impacts of oil prices on developing countries. Future studies building upon what Arlan and Mike have done are highly anticipated.

BLOG POSTS ARE PRELIMINARY MATERIALS CIRCULATED TO STIMULATE DISCUSSION AND CRITICAL COMMENT. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED ARE THOSE OF THE INDIVIDUAL AUTHORS. WHILE BLOG POSTS BENEFIT FROM ACTIVE UHERO DISCUSSION, THEY HAVE NOT UNDERGONE FORMAL ACADEMIC PEER REVIEW.

Trevor Fitzpatrick is a graduate student at the Department of Urban and Regional Planning (DURP) – University of Hawaii at Manoa