By John Lynham and Chaning Jang*

In light of declining global fish stocks, an immediate and important concern becomes the management of our fishery resources, both to protect the delicate ecosystems that they are a part of, and to ensure their viability as an economic and food resource for generations.

A controversial new method to manage fisheries is to assign “catch shares”. That is, grant fishermen or firms the right to land a certain amount of fish in any given year. From an economic perspective, assigning these rights (often referred to as individual transferrable quotas ITQs) has two potential benefits. First, because these ‘rights’ are transferrable, individuals and firms who value these rights the most have the ability to obtain them, by purchasing them from those who value them less. Second, having a long-term right to catch a certain share of the total catch may make share holders more willing to accept short-term reductions in catch in order to reap the benefits of recovered populations in the future.

Problems naturally arise when assigning these catch shares or ITQs. For one, we are commoditizing the rights to fish in the ocean. Second, there is a thorny issue in determining exactly how and to whom the catch shares should be allocated. Getting this process correct is absolutely critical to the success of implementing catch shares as a viable solution to our overfishing woes.

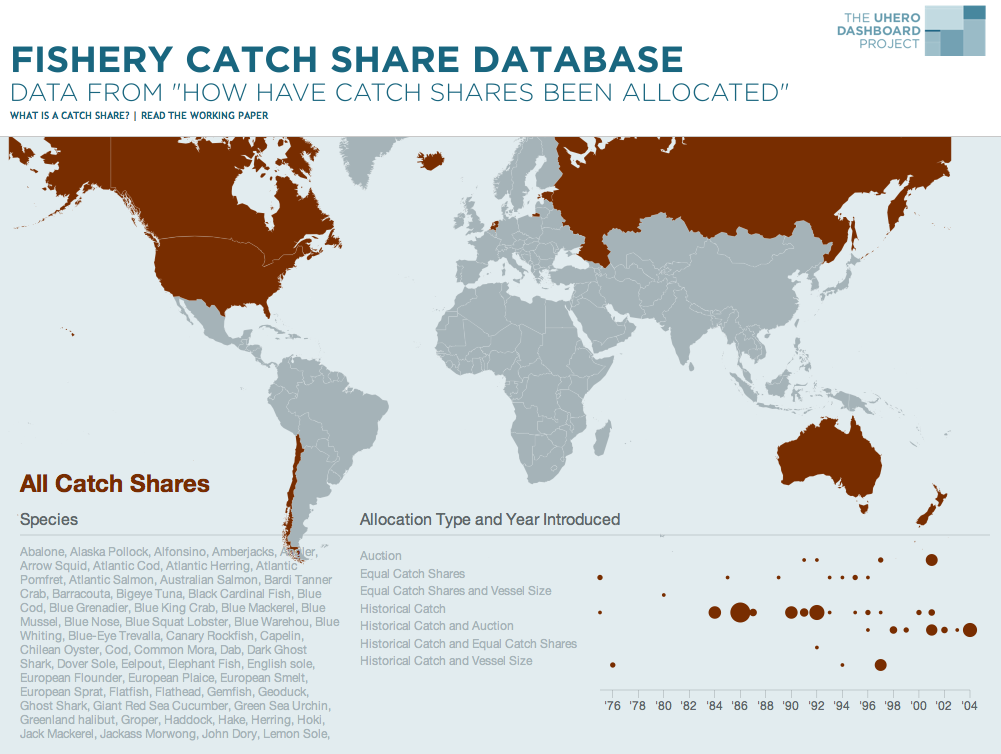

We have conducted research on catch share allocations around the globe, and our findings will soon be published in Marine Policy. We investigate how fishing rights were assigned in nearly every fishery in the world and have collected this information in a freely accessible database. Learning from others’ successes and failures in assigning catch shares will be critical to designing and implementing a system that works for Hawai’i.

These findings should be informative for policy makers. 54% of fisheries who implement catch shares do it on the basis of historical catch, that is, how much fish you have caught in the past. A full 91% use some sort of historical catch in their calculation methods, incorporating vessel-based rules (the size of your boat determines your allocation), auctions, and equal sharing. Interestingly, auctions – which most economists would argue to be the best method for allocating public resources – have failed to gain traction as a viable method of allocating catch shares. Just 3% of fisheries use this method, and many that have tried (Estonia, Russia, New Zealand, Chile) have either switched to different methods in the face of protest, or abandoned auctions as a mechanism in other fishery allocations.

Especially important to Hawai’i is the effect of any potential allocation system on native Hawaiian rights to their land and resources. The findings show that New Zealand first allocates 20% of their fish to their native Māori population before distributing the rest. Careful consideration must be taken to ensure that all possible stakeholders, whether they be multinational conglomerates, small local businesses or native populations, be adequately involved in the process and benefit from rights to quota-based fishing.

As Hawai’i continues to find sustainable ways to continue its fishing operations, we must be cognizant of the benefits and risks of all of our options. In understanding how catch shares have been allocated before, we can learn a lot about how they might best serve Hawai’i, if at all, in the future.

*Chaning Jang is a PhD Student at UH Manoa. He assisted John Lynham in this research and in writing this blog.

BLOG POSTS ARE PRELIMINARY MATERIALS CIRCULATED TO STIMULATE DISCUSSION AND CRITICAL COMMENT. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED ARE THOSE OF THE INDIVIDUAL AUTHORS. WHILE BLOG POSTS BENEFIT FROM ACTIVE UHERO DISCUSSION, THEY HAVE NOT UNDERGONE FORMAL ACADEMIC PEER REVIEW.