BLOG POSTS ARE PRELIMINARY MATERIALS CIRCULATED TO STIMULATE DISCUSSION AND CRITICAL COMMENT. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED ARE THOSE OF THE INDIVIDUAL AUTHORS. WHILE BLOG POSTS BENEFIT FROM ACTIVE UHERO DISCUSSION, THEY HAVE NOT UNDERGONE FORMAL ACADEMIC PEER REVIEW.

By Dylan Moore

How much more am I getting? I’m getting $80 a month before taxes, and I’m going to lose a $1000 benefit… It’s so stupid.

This quote—from a parent in California1—describes the frustrations that policy “cliffs” can cause for low-income working families. A “cliff” occurs when a large benefit is suddenly withdrawn when income exceeds some threshold, even if by only $1. As the quote suggests, cliffs are not only arbitrary and unfair, they can also reduce incentives to work and earn more. And under a new tax reform plan, these cliffs are coming to Hawai‘i.

If passed, the recently announced Green Affordability Plan (GAP) would be the largest tax reform in the state’s recent history, providing tax relief to all Hawaiʻi residents. However, in its current form, the GAP (SB1347/HB1049) also exacerbates cliffs in Hawai‘i’s tax code. In this post—the first in a series analyzing the GAP—I explain the problems these cliffs will create, and how the plan can be tweaked to eliminate them.2

Cliffs in the GAP

The GAP contains many provisions targeted to ALICE (Asset Limited, Income Constrained, Employed) households, particularly those with children. For example, it significantly expands the Credit for Low-Income Household Renters. Under the GAP, a couple with two kids earning $20,000/year who pay rent can receive $1400 by claiming this credit (up from $200). Any eligible resident can receive this money, even if they owe no taxes.

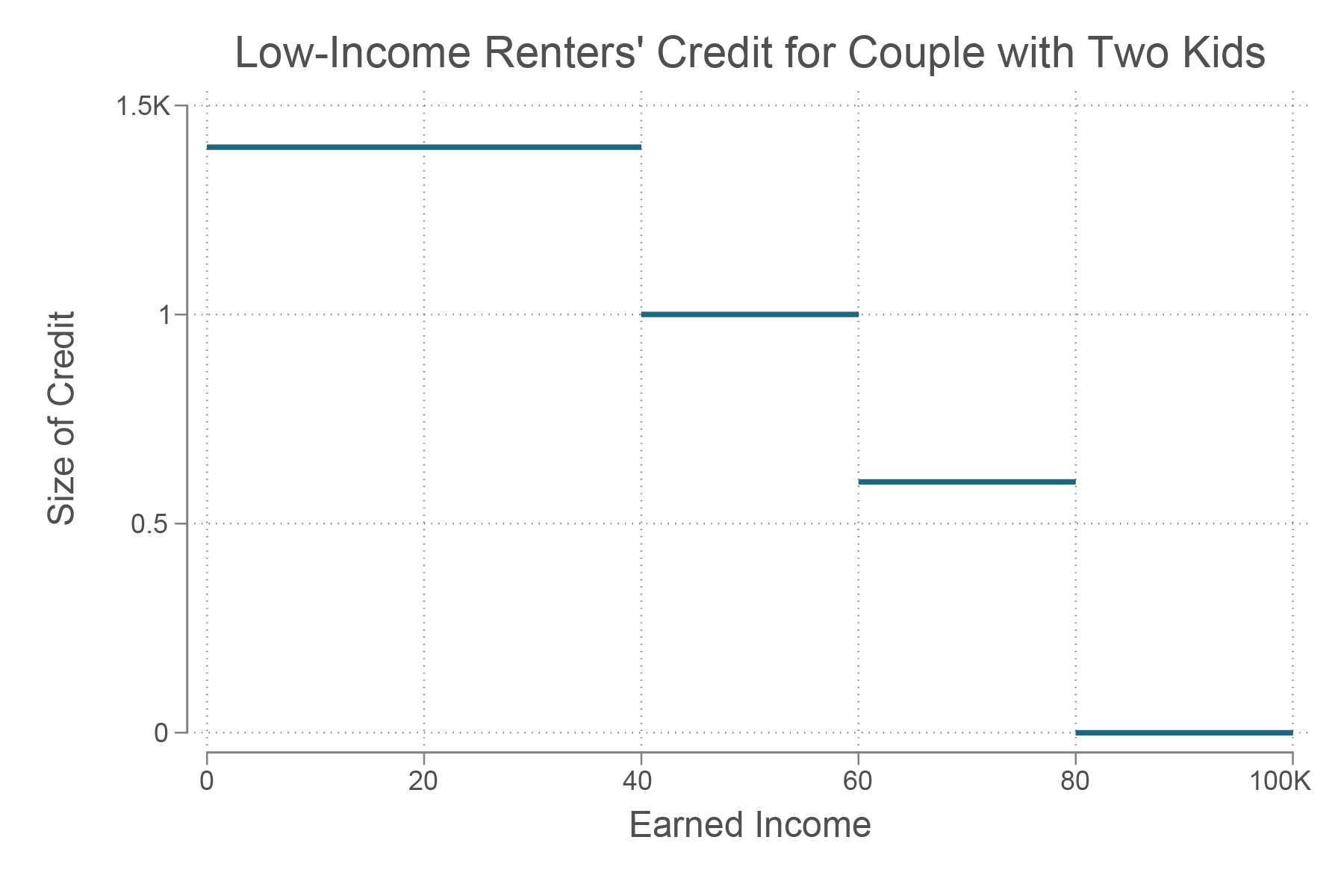

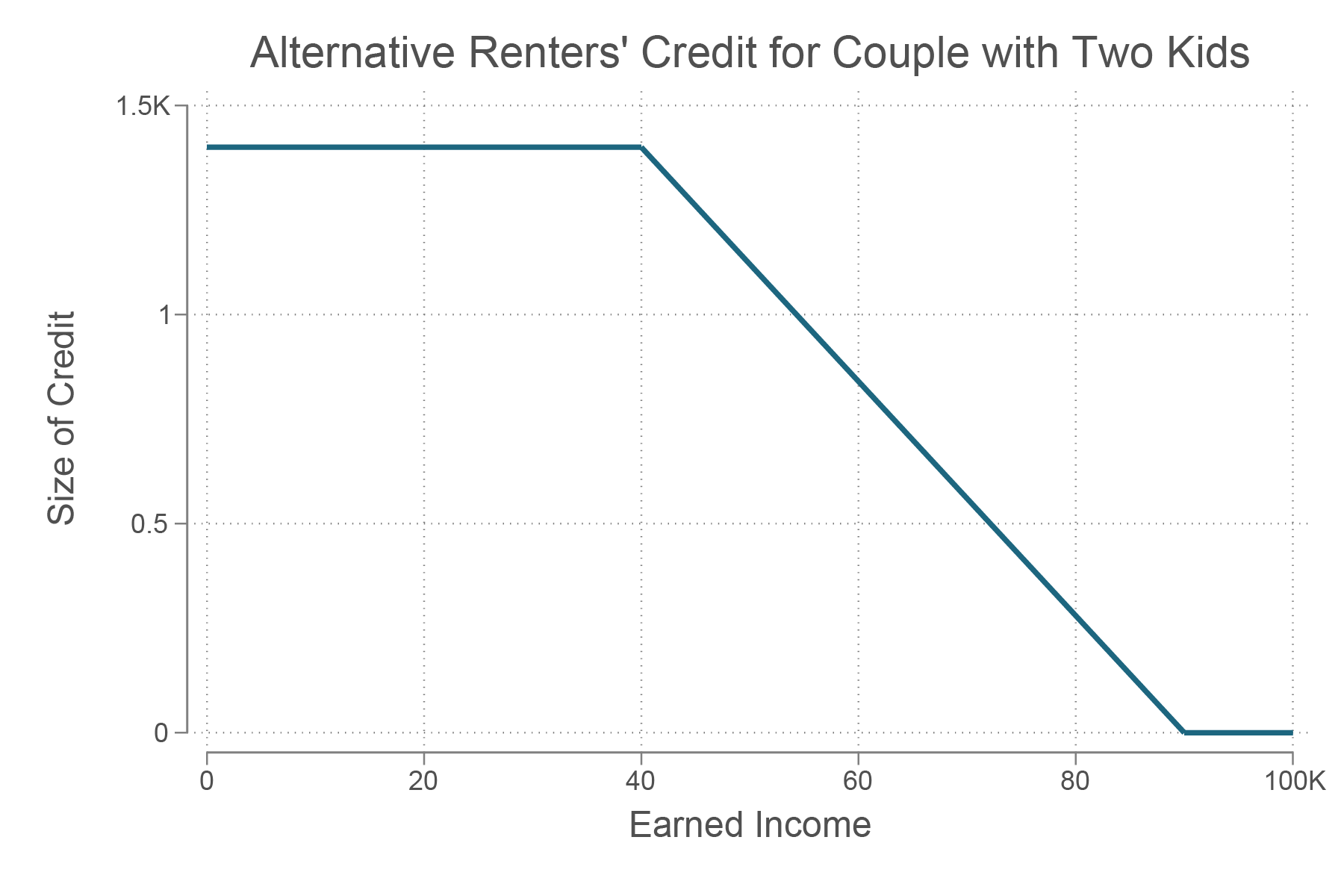

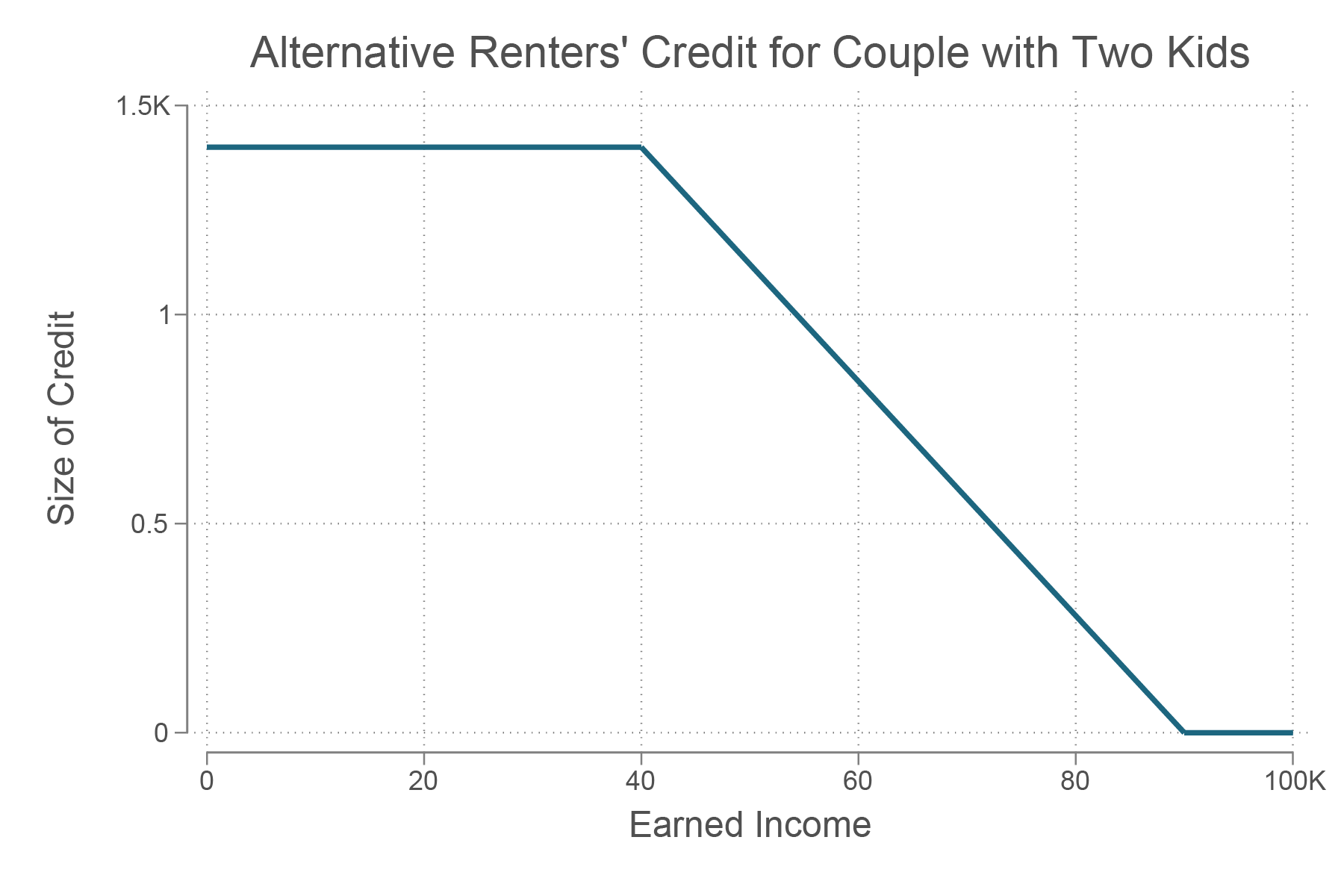

But not all residents are eligible. Consistent with the Governor’s focus on ALICE families, the expanded renters’ credit provides less money to higher income families. The figure below shows how the size of the credit varies with income for a couple with two kids.

The problem with this design is not that the credit falls with income. This ensures that the credit provides cost-effective assistance to ALICE households. If the state provided $1400 to every renting family of four, its cost would be much greater. Rather, the problem is the way in which the credit is reduced: via cliffs. For example, this family will lose $400 worth of tax credits if they “fall off” a cliff by earning $60,000 instead of $59,999.

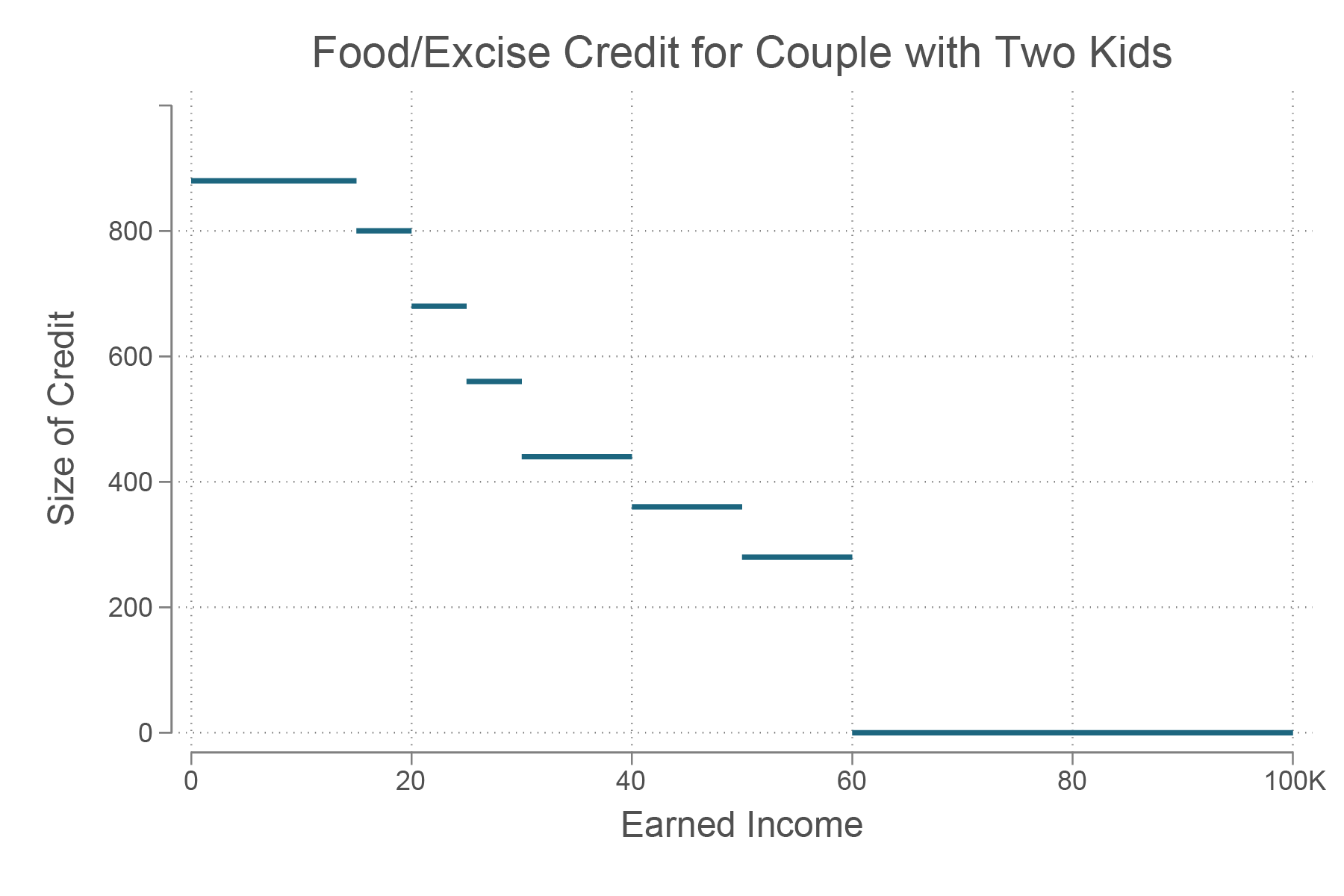

These are not the only cliffs this household will face under the GAP. The figure below shows how the Refundable Food/Excise Credit varies with income under the plan.

An Example

To see how these cliffs can impact ALICE families, let’s consider an example based on a real Hawai’i family appearing in US Census data.3 This married mother and father in their late-30s rent their home and have two children: an 11-year-old boy and a 14-year-old girl. The father, a veteran, now works as an engineer earning $58,960 annually. The mother earns no income, spending her time looking after the couple’s children, while also pursuing a graduate degree.

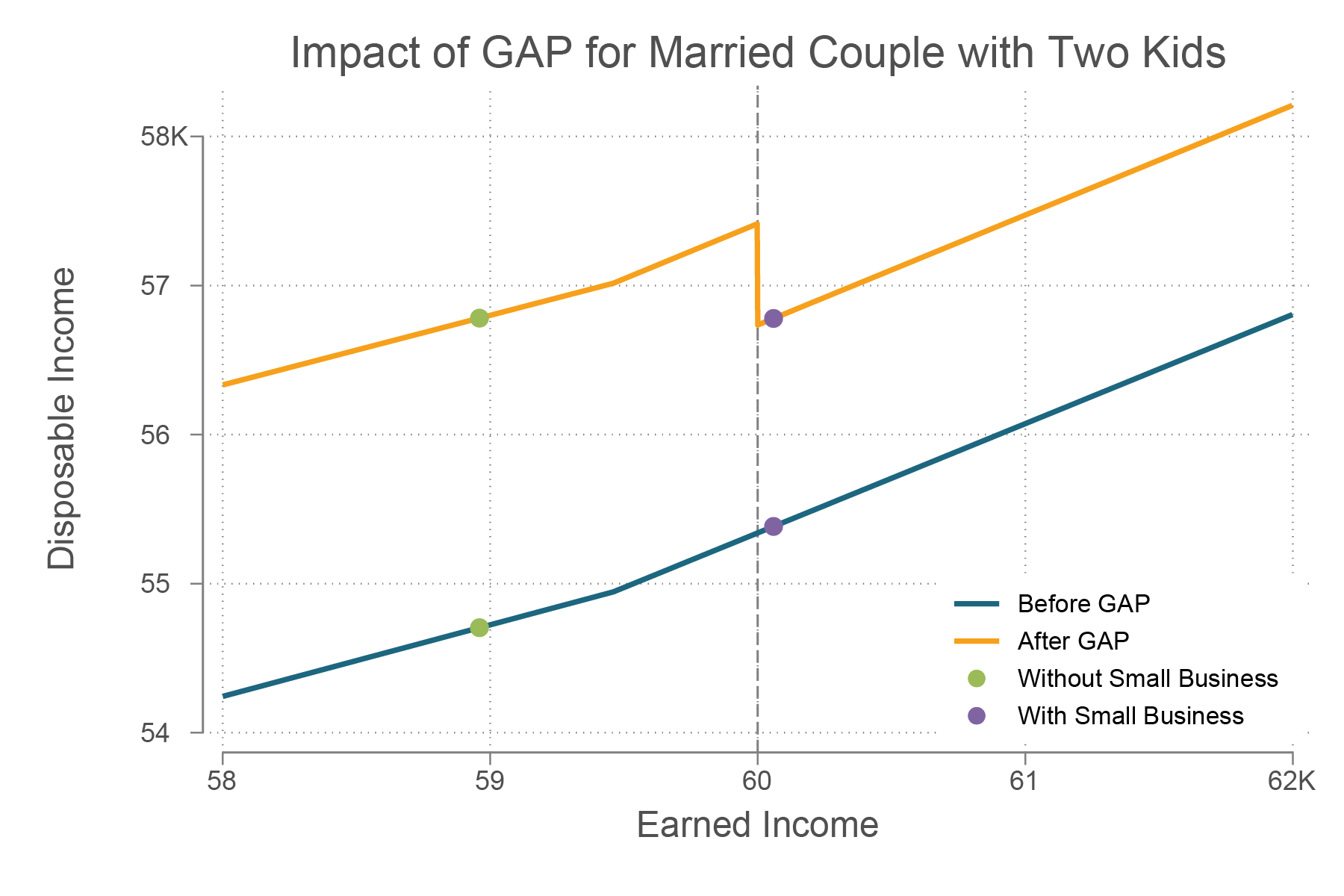

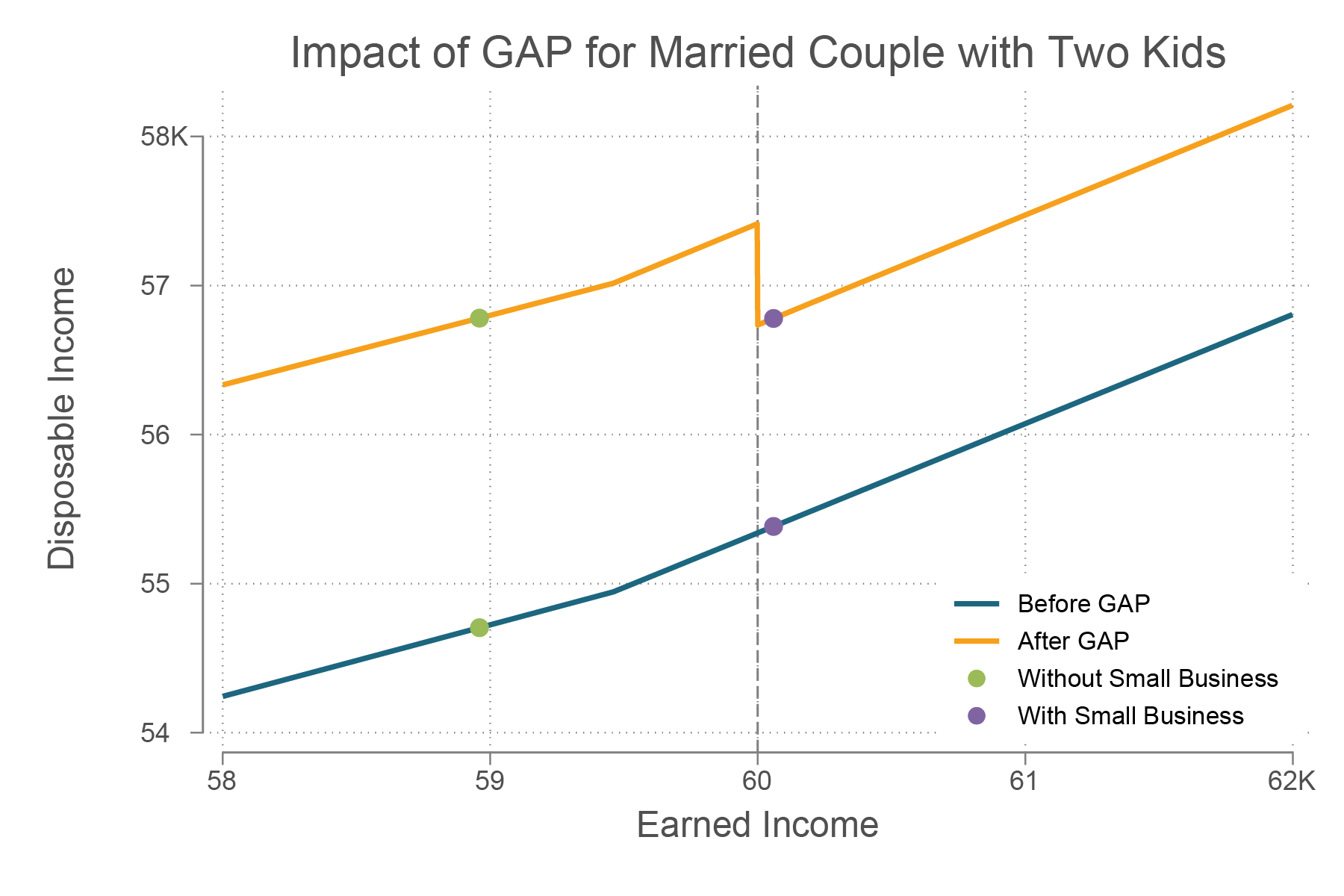

Suppose the mother completes her studies and decides to start a small business. This year, her profits will add $1,100 to their income, bringing the total to $60,060. The figure below depicts how the mother’s decision to start a business changes the household’s financial situation under the current tax system, and under the GAP.

The horizontal-axis is the income the couple earned this year and the vertical-axis is their disposable income: what they have after paying taxes and receiving credits/transfers (both state and federal). The blue line represents the relationship between this family’s earned income and their disposable income under the current tax system; the orange line, under the GAP.4 On each line, the green dot represents the financial situation of the couple if the mother chooses not to start a business; the purple dot represents their situation if she does start the business.

It is clear that the family will benefit greatly from the GAP. Whether or not the mother starts her business, the GAP increases their disposable income significantly. However, the GAP also changes the mother’s payoff from starting a business. Under the current tax system, the mother’s extra business income increases the household’s disposable income by about $679. By contrast, under the GAP, the $1,100 of extra income she earns this year will actually reduce her family’s disposable income by about $2.

The cause of this perverse outcome is a large cliff created by the GAP. When this family’s income goes from $59,999 to $60,000, they fall off the cliff, losing $280 of Food/Excise Tax Credit money and $400 in Low-Income Renters’ Credit money. Together with other aspects of the tax system, this cliff eliminates any extra disposable income that the mother might have hoped to provide by starting her business. Consequently, for this family, the GAP creates a powerful disincentive to earn additional income.

Who Cares?

Do these cliffs really matter? The mother may choose to start her business anyway, anticipating that greater profits in future years will make her work worthwhile. The couple may also be unaware of these cliffs when making financial decisions. Nonetheless, most observers would likely consider the effects of the cliff unfair. For ALICE households, $680 is a lot of money. Unless a household earning $60,000 is $680 less deserving than a household earning $59,999, these cliffs represent a significant design flaw, even if they don’t impact financial decisions.

Furthermore, cliffs do alter financial decisions. Researchers interviewing low-income families facing cliffs in Colorado and California found that many took steps to reduce their income to avoid losing a childcare subsidy.5,6 Some worked fewer hours, or even turned down raises to avoid falling over a cliff. In the second case, the cliff benefits the employer’s profits rather than the families the policy is targeting.

Countless empirical studies from all over the world have shown that some households do take steps to prevent themselves from falling over cliffs.7 In the US context, studies show that a sizeable minority of low-income households alter their (reported) income in order to maximize their tax credits. There is little doubt that some Hawai’i taxpayers would do so in response to the GAP’s cliffs.

Returning to our example, it is easy to see how this might happen. If the mother can reduce her business income for this year by just $61, the family’s income will fall from $60,060 to $59,999 and they will get $680 worth of tax credits.8 She could accomplish this in many ways: for example, she could reschedule some business expenses so they occur this year instead of next year.

Regardless of what tactics are used, the end result is the same: some households will reduce their income (either on paper or in reality) to avoid going over a cliff. This costs the state not only through the additional tax credit payments, but also by reducing the income tax liability of these individuals.

Other Cliffs in GAP

The GAP—as currently proposed—creates many additional cliffs. Below are a few examples.

- Example #1: Single Parent Renter with Two Kids

Earning $60,000 instead of $59,999 will cost this household $510: $300 from the renter’s credit and $210 from the food/excise credit. - Example #2: Elderly Couple Renting Their Home

Earning $60,000 instead of $59,999 will cost this household $540: $400 from the renter’s credit and $140 from the food/excise credit. - Example #3: Families with Childcare Costs

An expanded child and dependent care tax credit also creates a series of cliffs at $150K, $165K, $180K, $195K, $210K, and $225K. For taxpayers paying for childcare for two kids under 13, going over these cliffs costs as much as $1000.9

The Solution

Fortunately, this is not a difficult problem to solve. Cliffs are only one way to design tax credits targeting low-income residents. Alternatively, tax credit size can decline gradually as income increases. For example, an alternative version of the new Credit for Low-Income Household Renters might look like this.

The credit remains targeted, providing reduced benefits at higher incomes. But the reduction happens gradually. For each additional dollar a household earns over $40,000, they lose only a fraction of the credit. Consequently, any increase in the household’s earnings will lead to an increase in their disposable income.10 This eliminates the significant fairness and disincentive effects the cliff approach creates.

Conclusion

In the pursuit of providing cost-effective assistance to ALICE families, the designers of the GAP introduced a flaw: cliffs. While the bill will help these families, the use of cliffs is inconsistent with principles of good tax design. It is also unnecessary. Targeted assistance can be effectively provided using credits that gradually fall with income. In response to feedback from UHERO, the Governor’s office is considering amending the GAP to do exactly this. This common sense approach would bring Hawai‘i in line with the approach now taken at the federal level, where targeted policies like the Earned Income Tax Credit do not include any cliffs.

But eliminating cliffs does not mean the GAP has no disincentive effects. Gradual credit reductions still decrease the extra disposable income generated by additional earnings. A future post will discuss these more subtle incentive effects of the GAP.

Footnotes

1 Roll, Susan (2018). Examining the Child Care Cliff Effect in a Rural Setting. Social Work & Society.

2 UHERO has shared this blog and other analysis with the Green administration and we expect to see amendments forthcoming that would eliminate the cliffs described here by using a gradual-phase out of credits, as described later in the post.

3 From the 2020 CPS ASEC.

4 This figure reflects the impact of all GAP provisions on this household, not just the renters’ and food/excise tax credit expansions.

5 Roll, Susan (2018). Examining the Child Care Cliff Effect in a Rural Setting. Social Work & Society.

6 Roll, Susan & East, Jean (2014). Financially Vulnerable Families and the Child Care Cliff Effect.

7 For example: Hamilton, S. (2018). “Optimal deductibility: Theory, and evidence from a bunching decomposition.”

8 Mortenson, Jacob A., and Andrew Whitten (2020). Bunching to Maximize Tax Credits: Evidence from Kinks in the US Tax Schedule. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy.

9 For a household with $20,000 or more in child care costs.

10 At least, as long as tax rates are not too high and there aren’t too many tax credit reductions happening too rapidly at the same levels of income.