BLOG POSTS ARE PRELIMINARY MATERIALS CIRCULATED TO STIMULATE DISCUSSION AND CRITICAL COMMENT. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED ARE THOSE OF THE INDIVIDUAL AUTHORS. WHILE BLOG POSTS BENEFIT FROM ACTIVE UHERO DISCUSSION, THEY HAVE NOT UNDERGONE FORMAL ACADEMIC PEER REVIEW.

By Veronica Gibson, Leah Bremer, Kimberly Burnett, Nicole Keakaonaaliʻi Lui, and Celia Smith

“I think about the anchialine pools and the significance of the anchialine pools and how, if you have anchialine pools in your ahupuaʻa, especially in a place like North Kona, Kekaha Wai ʻOle,… you’re considered very wealthy” ~ anchialine pool resource manager

“It [working in the loko iʻa] feeds us spiritually and emotionally, it brings us together as a community…So, feed can mean many things.” ~ loko ʻia (fish pond) resource manager”

Drawing from Indigenous management principles, the Hawaiʻi State Water Code is among the first to encode holistic water management into law (Sproat 2015). Specifically, the public trust doctrine described by the Hawaiʻi Supreme Court as, “the right of the people to have the waters protected for their use [which] demands adequate provision for traditional and customary Hawaiian rights, wildlife, maintenance of ecological balance and scenic beauty, and the preservation and enhancement of the waters” (HRS 174C-2), aims to protect the multiple ecological and social uses of waters. However, the implementation of the public trust doctrine has lagged behind, in part because the inclusion of ecological and social values of water remains insufficient. [1]

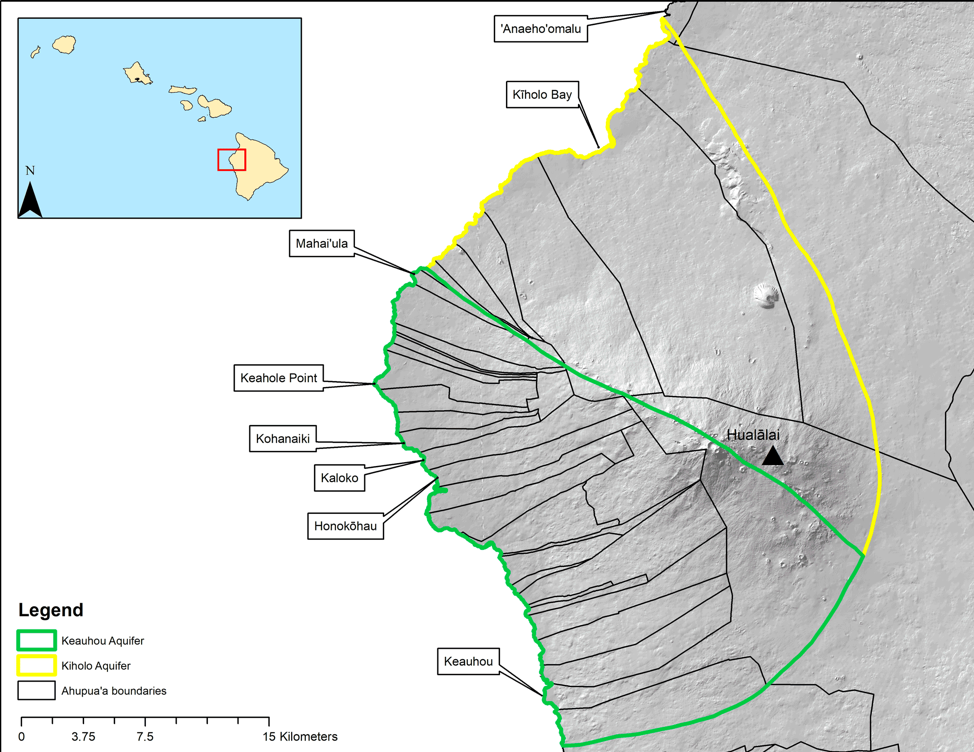

In response, our recent collaborative study published in Ecology and Society, by UHERO, the Water Resources Research Center, the Botany Department, and members of the Kona community, seeks to illuminate the important social values of an important public trust resource, “groundwater dependent ecosystems” (GDES) or ecosystems that depend on clean flows of groundwater. These GDEs include loko iʻa (Indigenous aquaculture systems or fish ponds), loko wai kai (anchialine pools), and muliwai (nearshore estuarine ecosystems) (Figure 1). Historically, GDEs were a primary source of water and food for coastal communities in Kona, and these systems continue to have important cultural, social, and ecological value today (see study area in Figure 2).

Through a literature review and interviews with 19 lineal descendants and GDE resource managers, our study focused on the following questions:

(i) In what ways are GDEs used, valued, and cared for in Kona currently and historically?;

(ii) What are the major perceived threats to these systems?;

(iii) What are resource managers’ and lineal descendants’ visions for future use and management of these systems?

Our research found that GDEs have deep social and cultural value, in part tied to their historical significance as the major water source and important food production systems for Kona. As part of their storied history, GDEs feature prominently in moʻolelo (stories/legends). Although not used as primary drinking water sources today, recognition of the historical importance of the pools and springs supports connection to kūpuna (ancestors) and to ancestral knowledge and practice. In our interviews, many spoke of this important biocultural value, and restoration of these systems focuses on the mutual restoration of ecosystems and culture.

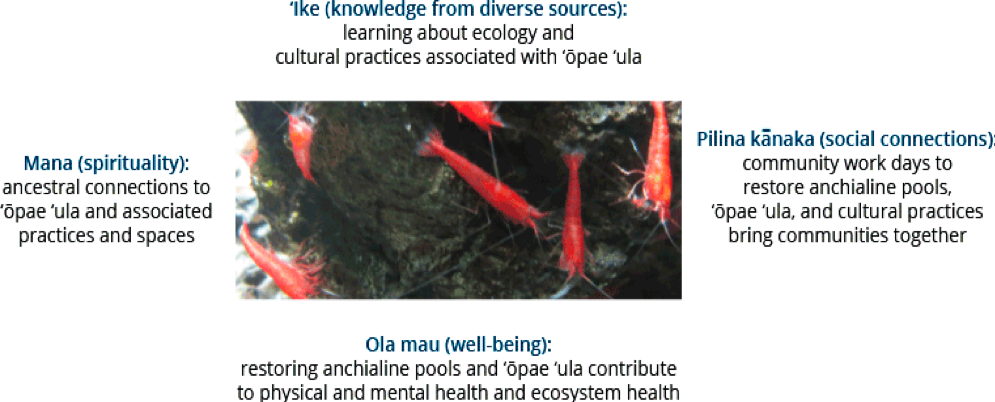

The ʻōpae ʻula (the Hawaiian anchialine pool shrimp) helps to illustrate the biocultural importance of GDEs, including their importance for pīlina (social connections), mana (spirituality), ola mau (well-being), and ʻike (knowledge)2 (Figure 3). ʻŌpae ʻula are considered an important biocultural indicator of healthy anchialine pools, as stated by a Kanaka ʻŌiwi resource manager: “Anchialine pools have a lot of different purposes and one of the major purposes is to supply, to be home for ʻōpae ʻula… So once we see an abundance of ʻōpae ʻula come back, that’s when we can begin thinking of the reinstatement of practices again.”

Figure 3: Biocultural values of ʻŌpae ʻula using a cultural ecosystem services framework [2]

Threats to GDEs

“As with most of Hawaiʻi, our sacred and/or special places see more people, exposure, commodification, and at times, destruction. In today’s society of social media and Instagram celebrities, I see instances where people are willing to go to the extremes in order to ‘get the shot’ that will get them the most ‘likes’ even if they may not be aware of the negative impact they may be having on these places or people.” ~ Kānaka ʻŌiwi resource manager

We also found that there are important threats to GDEs including invasive species, sea level rise, nutrient pollution, over use, reduced groundwater flow, and urban development. Managers work to control invasive species, particularly invasive guppies, which is one of the most direct threats to anchialine pools. Other threats require broader interventions in watershed management. Other challenges, including wastewater and watershed management and increased visitation, are often beyond the direct control of on-site managers and require policy action at the state and county levels.

Visions of the future

“We also need to understand that the process is very important. If the process is not pono [correct and proper] then the outcome is never pono.” ~ Kānaka ‘Ōiwi resource manager

Interviewees expressed visions of restoration of GDE ecological and social functions. There was an emphasis on the process of restoration being as important as the outcome, and that the restoration of cultural practice, well-being, and identity is critical. Managers continue to address the threats they have the most direct control over (e.g. invasive guppies), but they also emphasize the importance of shifting decision-making power to local resource managers and exploring models of community-based governance and Indigenous knowledge-based management of these systems. They also suggested limiting visitation to allow for “resting” of GDEs and creating a fee-based or tax-based system to fund docents for education and GDE maintenance. Others suggested increasing setback laws to protect existing GDEs and allow space for creation of new GDEs inland as expected with rising sea levels. Some further highlighted the need for aquifer-wide interventions to prevent declines in SGD quality and quantity, particularly in the context of threats derived from climate change and future development.

The Indigenous people of Kona have a long history of resilience and adaptation that is instrumental in successfully facing challenges in GDE management. In the face of many interacting challenges, the Kona community is at the forefront of combining Indigenous knowledge and resource management practices with contemporary technology for GDE restoration. Supporting local resource managers, cultural practitioners, and lineal descendants in achieving these goals through re-orienting governance and funding toward community-based management will be critical to the long-term ecological and social health of these important systems.

For more information see the full study in Ecology and Society.

Acknowledgements: First and foremost, we are grateful to the caretakers of GDEs in Kona who took the time to share their knowledge and experiences with us. We also thank the Institute of Hawaiian Language Research and Translation (particularly ʻAnoʻilani Aga, Kilika Bennett, and Uʻilani Au) for their collaboration and work translating nūpepa from Kona and Gina McGuire for creating the study area map. This project was funded by the NSF Hawaiʻi EPSCoR Program through the National Science Foundation’s Research Infrastructure Improvement award (RII) Track-1: ʻIke Wai: Securing Hawaiʻi’s Water Future Award # OIA-1557349 and the USGS Water Resources Research Institute Program Award # G16AP00049 BY5. We thank the research teams involved in each of these project.

1 Sproat, D. K.. 2015 From wai to kānāwai: Water law in Hawai‘i, in native Hawaiian law: A Treatise. MacKenzie, Serrano, & Sproat eds. Kamehameha Publishing. Honolulu, Hawaii.

2 Pascua, P., H. McMillen, T. Ticktin, M. Vaughan, K.B. Winter. 2017. Beyond services: A process and framework to incorporate cultural, genealogical, place-based, and indigenous relationships in ecosystem service assessments. Ecosystem Services. Putting ES into practice 26, 465–475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.03.012