BLOG POSTS ARE PRELIMINARY MATERIALS CIRCULATED TO STIMULATE DISCUSSION AND CRITICAL COMMENT. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED ARE THOSE OF THE INDIVIDUAL AUTHORS. WHILE BLOG POSTS BENEFIT FROM ACTIVE UHERO DISCUSSION, THEY HAVE NOT UNDERGONE FORMAL ACADEMIC PEER REVIEW.

By Timothy Halliday

Policy Background [1]

Under the Compacts of Free Association (COFA), citizens from three nation-states located in the Pacific Ocean (the Republic of Palau, the Republic of the Marshall Islands, and the Federated States of Micronesia) are given free entry to the United States. In return, the United States military has access to their ocean territories. The US has also agreed to support these nations in health and other social investment. COFA migrants are allowed to enter and work in the US. However, COFA migrants are not eligible for federal Medicaid coverage under the 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act.

In the wake of this federal legislation, states are left to decide if they wish to support the Medicaid enrollment of COFA migrants with limited means. With some interruption, the State of Hawaii did enroll COFA migrants in its Medicaid program. However, in March 2015, following a legal decision, the State of Hawaii revoked coverage in the state Medicaid program for non-blind, non-disabled, non-pregnant COFA migrants aged 18 to 64. Instead, individuals in this group could obtain Medicaid-subsidized private insurance in exchanges established by the ACA under either of the two market dominant health insurers in the State of Hawai‘i.

Impacts of the Medicaid Expiration on COFA Migrants

Medical Utilization Declined

The expiration of Medicaid benefits resulted in a decline of medical utilization. Specifically, there was a sharp reduction in the number of emergency and in-patient medical care admissions charged to Medicaid after the expiration of program benefits for COFA migrants relative to the non-Hispanic white and Japanese populations in Hawaii among people ages 18 to 64. Medicaid-funded ER visits and inpatient admissions declined by 31% and 19%, respectively. At the same time, there was a substantial increase in the number of emergency room (ER) visits and inpatient admissions charged to private payers, indicating that there was a move towards private insurance among COFA migrants after Medicaid program benefits expired. However, the magnitude of this increase was smaller than the reduction in Medicaid-funded utilizations. As a result, net inpatient admissions and emergency visits declined. Finally, there was a substantial decline in Medicaid funded utilization for Micronesian children despite the fact that the expiration did not impact them.

Uninsured Visits to the ER increased

The expiration of Medicaid resulted in an increase in uninsured visits to the ER among COFA migrants. The magnitude of this effect is 25% as large as the estimate of the impact of the Medicaid expiration on Medicaid-funded ER visits. This indicates that part of the impact of the Medicaid expiration on utilization was offset by uninsured visits to the ER. It also provides strong evidence that the Medicaid expiration left many COFA migrants without insurance despite the availability of premium subsidies for private insurance. Importantly, the increase in uninsured ER visits pre-dated the official expiration of Medicaid eligibility indicating that there were uninsured COFA migrants being treated in hospitals despite the fact that they were eligible for Medicaid benefits at that time.

Mortality Increased

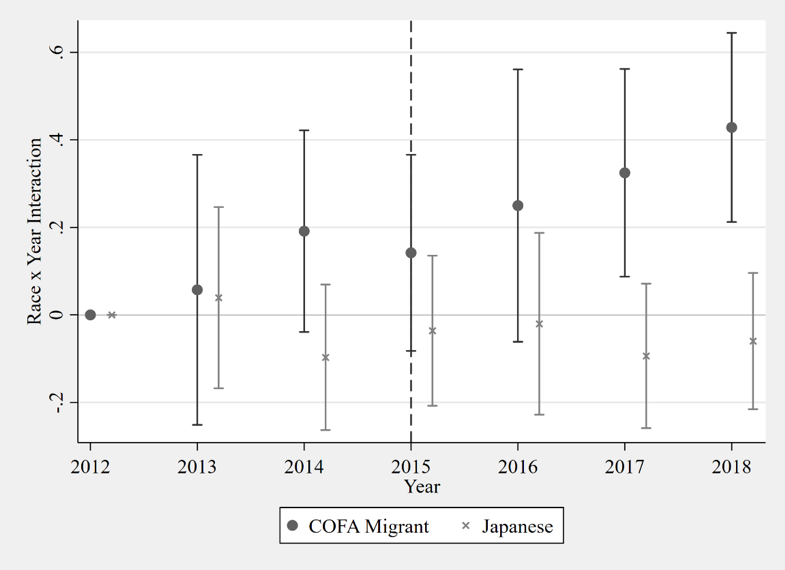

The decline in medical utilization resulted in higher mortality rates for COFA migrants. Using vital records from the Hawaii Department of Health, researchers showed that mortality rates of COFA migrants increased by 21% over the period 2015-2018. This can be seen in the figure below.

An Unknown Number of COFA Migrants Lack Insurance

A large but unknown number of COFA migrants do not have insurance. This is underscored by the dramatic increase in uninsured ER visits by COFA migrants previously discussed. In addition, we know that during the initial transition period in March 2015, 5500 COFA migrants were automatically enrolled in a plans administered by HMSA and 3600 migrants were automatically enrolled in plans administered by Kaiser. This automatic transition happened once. Subsequently, COFA migrants had to enroll themselves in private plans. This process was made difficult by the exchanges not being available in Micronesian languages and the fact that enrolling in private insurance first necessitates applying for Medicaid and getting proof of rejection before migrants can enroll in private insurance plans. In 2017, 3225 COFA migrants received premium assistance whereas this number in 2015 was approximately 9100. This suggests that at least 6000 COFA migrants were uninsured in 2017. The population of Micronesians in Hawaii is about 27,000. Consequently, by this estimate, the Medicaid expiration increased the proportion of uninsured COFA migrants by at least 22 percentage points.

Implications for COVID19

COFA migrants most likely have been disproportionately impacted by COVID19. In fact, the Hawaii State Department of Health estimates that Pacific Islanders (excluding Native Hawaiians) are over-represented in COVID19 cases by a factor of five.

It is important to interpret this in light of the expiration of Medicaid benefits for this population. The large numbers of uninsured migrants suggests that many will be reluctant to seek out medical care when feeling ill. Indeed, it has been shown that utilization declined after Medicaid benefits for Micronesian adults expired. As a result, many cases of COVID19 might go undetected in this community due to a reluctance to seek out care.

This is problematic for many reasons. First and foremost, it places the health of an already vulnerable population at greater risk. Health outcomes are generally very poor in this community and so COVID19 will hit them particularly hard. Experience has shown that COVID19 disproportionately impacts communities with pre-existing conditions which often are common in communities of color. Life expectancies in Micronesia range from 65 for the Marshall Islands to 70 for Palau. This suggest that COFA migrants may be the least healthy of any ethnic group in the United States. Second, the potential for many clusters in this community is high as household sizes tend to be large and many are essential workers who cannot work remotely. In Singapore, a recent second wave of COVID19 was fueled by tightly packed housing among migrants. Australia has had a similar experience in its migrant communities. These risks are arguably greater in Hawaii where COFA migrants often lack insurance. Third, language barriers, difficulties locating people in this community, and possible lack of trust due to a traumatic history could make contact tracing difficult. Finally, lack of insurance coverage among many COFA migrants implies that health care providers will be forced to provide charity care that may be of lesser quality and financial burdensome to providers.

Policy Implications

What are the policy implications? While there are no easy solutions, increasing the rates of insured migrants could go a long way towards mitigating some risks. The State could place pressure on Hawaii’s Congressional delegation to reinstate Medicaid benefits for COFA migrants which requires an act of Congress. However, the mistake that disqualified COFA migrants from federal Medicaid has been in place for 25 years and there is no reason to expect this to change anytime soon. The State might also consider re-transitioning COFA migrants to the State’s Medicaid program, but given the State’s fiscal position that also seems unlikely.

However, the State does have policy levers that might work if there is a political will. First, in all likelihood, private insurance companies lose money by insuring COFA migrants. In scenarios when the federal government subsidizes insurance premiums in private markets, it often pays an additional subsidy to insurance plans that insure sicker people through a process called risk adjustment. A system of risk adjustment would incentivize private insurance companies to insure more COFA migrants, while potentially being less expensive than reinstating Medicaid. Second, the State might consider financial incentives for COFA migrants who successfully enroll in private insurance plans. This would increase coverage rates and provide some financial assistance to this community. Third, given the extraordinary circumstances of COVID19, the State should encourage private insurers to extend their open enrollment period for COFA migrants. The six week open enrollment period for private insurance appears to be an important barrier to obtaining coverage.

However, these proposed solutions miss an important point. The ACA exchanges on which the State’s policy is based were never intended to provide coverage to vulnerable populations. Medicaid is the safety net that covers the poorest. Hawaii’s experience with COFA migrants vividly illustrates the pitfalls of relying on private insurance exchanges when covering the poor and the vulnerable.

Conclusions

The expiration of Medicaid for most COFA migrants has increased the number of uninsured migrants and reduced their medical utilization. It is currently killing about 50 COFA migrants per year. Given this, it is not clear that the United States is honoring the terms of the COFA. As a State, we must ask ourselves if allowing Medicaid benefits to expire was an ethical decision even if it turns out to have been a legal one.

[1] This policy discussion is heavily based on a recent publication in the American Journal of Public Health by the author of this op-ed and several colleagues that is located here.

Photo by Fusion Medical Animation on Unsplash