BLOG POSTS ARE PRELIMINARY MATERIALS CIRCULATED TO STIMULATE DISCUSSION AND CRITICAL COMMENT. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED ARE THOSE OF THE INDIVIDUAL AUTHORS. WHILE BLOG POSTS BENEFIT FROM ACTIVE UHERO DISCUSSION, THEY HAVE NOT UNDERGONE FORMAL ACADEMIC PEER REVIEW.

By Conrad Newfield, Nathan DeMaagd, Christopher Wada, Kimberly Burnett, and Leah Bremer

Kaua‘i’s native forests play a vital role in sustaining the island’s freshwater resources. These biodiverse ecosystems capture rainfall and fog, allowing water to seep into underground aquifers, which serve as the primary source of drinking water. However, the expansion of invasive plants and ungulates can change how these forests function. Without conservation action, the expansion of invasive canopy can increase water use rates of plants, leading to reduced groundwater recharge, increased runoff, and long-term declines in water availability.

A recent study by the University of Hawai‘i Economic Research Organization (UHERO), Institute for Sustainability and Resilience (ISR), and Water Resources Research Center (WRRC) in partnership with The Nature Conservancy (TNC), assessed the return on investment (ROI) of conservation efforts aimed at protecting Kaua‘i’s watersheds. The study analyzed existing and potential conservation fence units, evaluating their impact on groundwater recharge and the cost-effectiveness of these interventions over a 50-year period.

Watershed Conservation and Its Role in Groundwater Recharge

Healthy native forests help regulate the water cycle by promoting infiltration and reducing surface runoff. In contrast, invasive plants tend to have higher water consumption rates (evapotranspiration), leaving less water available for groundwater recharge. Additionally, feral pigs and deer contribute to soil degradation by uprooting vegetation and creating pathways that increase erosion and runoff. These combined factors can reduce the amount of water that seeps underground, ultimately lowering aquifer recharge rates.

To mitigate these threats, conservation efforts on Kaua‘i focus on fencing and active land management. Protective fences prevent invasive animals from entering native forests, while management efforts involve removing feral animals and controlling invasive plant species. By implementing these strategies, conservation organizations aim to slow the spread of invasive species, promote native forest recovery, and improve water retention within protected areas.

Study Approach and Key Findings

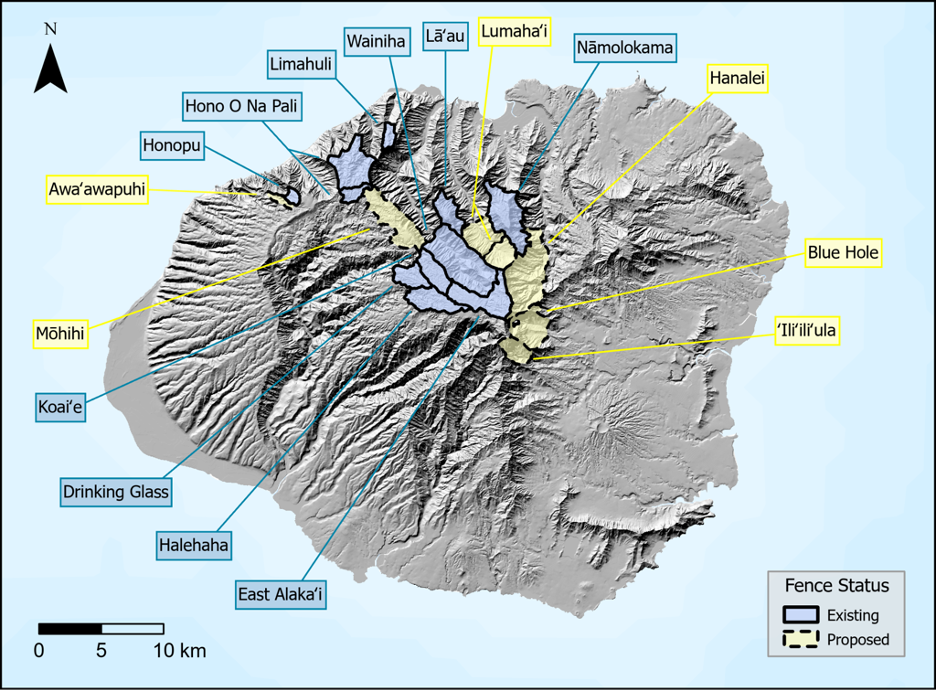

To understand the benefits of management, we looked at two conservation scenarios: one that maintains existing fenced areas and another that expands conservation efforts by adding new, proposed fences (Figure 1). We then modeled how forest cover (i.e. native vs. non-native cover) would change under the two conservation scenarios and compared this to what the forest might look like without any protection. We coupled this with a water balance model that allowed us to look at how conservation actions could influence groundwater recharge. Finally, we estimated conservation costs, including fence construction, maintenance, and invasive species management so we could look at gallons of groundwater recharge protected per dollar spent on conservation.

Figure 1. Existing and proposed native forest fence areas on Kauaʻi (> 200 acres). Note that proposed fences are hypothetical, not in progress.

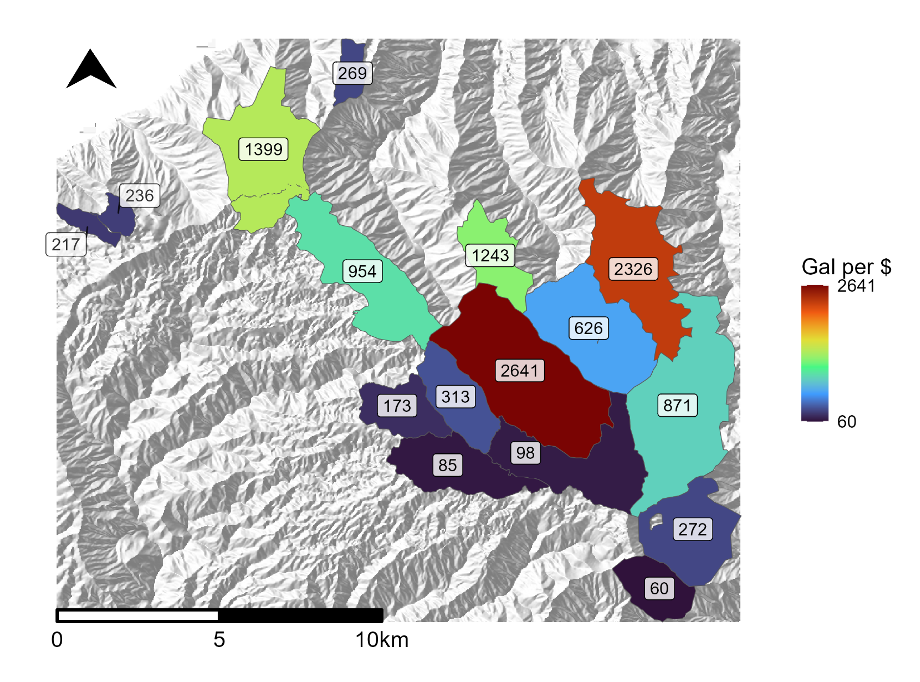

We find that conservation efforts provide a strong return on investment in terms of groundwater recharge. On average, each dollar spent on watershed protection leads to 593 gallons of groundwater recharge. In areas where natural barriers reduce fencing costs, such as Wainiha and Nāmolokama, ROI is significantly higher, reaching up to 2,625 gallons per dollar invested.

Figure 2. Return on investment for existing and potential fence units (gallons per dollar)

Expanding conservation efforts to include proposed fenced areas slightly lowers the average return to 567 gallons per dollar, with a range of 60 to 2,641 gallons per dollar invested (Figure 2). Over a 50-year period, however, cumulative groundwater recharge is projected to grow from 21.4 billion gallons under existing conservation to 34.4 billion gallons with expanded efforts. While the cost-effectiveness of conservation measures varies across different areas, the study demonstrates that long-term benefits continue to accumulate over time.

Spatial Considerations and Long-Term Benefits

The effectiveness of watershed conservation efforts depends on several factors, including elevation, rainfall patterns, and the rate of invasive species spread. We found that mid-elevation areas often provide the highest groundwater recharge benefits per dollar invested. These regions are more susceptible to invasion and, without intervention, could experience significant reductions in water availability.

Higher-elevation areas, while playing a crucial role in biodiversity conservation, tend to have lower recharge benefits in the short term. However, over longer time horizons, conservation in these regions will become increasingly important as invasive species continue to spread. The study also highlights that the use of natural barriers, such as steep cliffs and ridgelines, can enhance cost efficiency by reducing the need for extensive fencing.

Beyond groundwater recharge, watershed conservation provides a suite of linked cultural, social, ecological, and economic benefits. For example, protecting native forests supports high levels of ecologically and culturally valued biodiversity and helps reduce erosion and sedimentation, which can impact streams and nearshore ecosystems. Healthy watersheds also contribute to climate resilience by maintaining steady water supplies during periods of drought. While hydrological benefits were the primary focus of the study, these broader ecological, cultural, and economic considerations are also relevant when evaluating conservation investments.

Looking Ahead: Investing in Kaua‘i’s Future

In sum, this study demonstrated important groundwater recharge benefits of watershed conservation on Kaua‘i. The findings indicate that existing conservation efforts have been strategically implemented in high-impact areas, delivering significant returns in terms of groundwater recharge. Expanding these efforts would further enhance water security for the island.

While conservation costs are largely front-loaded, long-term benefits continue to accumulate, supporting both water sustainability and broader ecosystem functions. This work contributes to a broader understanding of how conservation investments can be evaluated in hydrologic and economic terms, providing a framework for future decision-making regarding watershed management on Kaua‘i and beyond.