By Leah Bremer and Kate Brauman

(In Press at the Global Water Forum)

Watershed management programs that promote land management like reforestation, conservation, and lower-intensity grazing to enhance clean and ample water supplies downstream are becoming more common around the world. To achieve their water goals, they often need hydrologic information, usually generated through field measurements and hydrologic models. However, hard work by the hydrologic community to provide this information, particularly in places with little hydrologic data and few examples of well-calibrated models, often go unused. We find that hydrologic scientists are often not providing the information program managers need.

In a recent article in Water Resources Research, we took a deep dive into three Water Producer Projects, a type of watershed management program in the Atlantic Forest region of Brazil. We interviewed a wide range of participants in Brazil to better understand how stakeholders actually use or want to use hydrologic information.

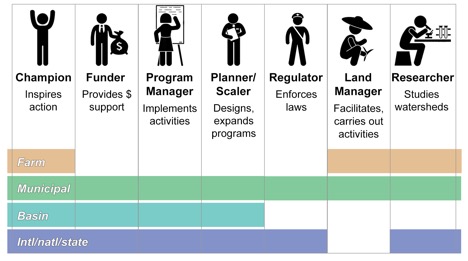

If we to produce useful science, we first need to understand who will actually use the information and for what purpose. From the three watershed management programs we worked with, we identified 7 general types of stakeholders, each of whom facesdifferent decisions and is interested in different types of hydrologic information. The figure above shows the roles and scales at which each type of stakeholder tends to work. We found that strong champions, those who inspire action, are important locally as well as internationally: All three programs existed because strong local and regional champions galvanized support. Programs also need funders to support them, program managers to organize and implement action, planners/scalers to design new projects locally and around the world, regulators to enforce environmental laws, and land managers to carry out activities on the ground. We also find that researchers play an important role in identifying what actions to take.

These users interact with hydrologic information in 5 distinct decision contexts. Understanding those decisions contexts and their different requirements of hydrologic information can help scientists design measurements and models that will be used. Though the decision contexts we identify are iterative and decisionmakers frequently move back and forth among them, we present them here in their most common chorological order.

Decision context 1 – Inspire action and support:

As hydrologic scientists, we sometimes assume models inspire action by illuminating connections between land management and water. In reality, however, it is people, not models, who inspire action. Each of our case studies demonstrated this, with compelling local and regional champions who galvanized support for their project. These champions often used examples and general principles from hydrology, but we didn’t talk with anyone who inspired a program based on a specific local study. Providing information to support champions who inspire and communicate a general appraoch is critical.

Decision context 2 – Informing investment decisions:

Do water companies and other potential funders of watershed management programs make all their decisions based on r economic costs and benefits? We found that while most funders do care about the economic bottom line, most funding for watershed management programs came from municipal and civil society actors who provide funding based on broad environmental and social goals, not just hydrologic outcomes. In this context, modeling studies, when delivered by trusted sources and packaged as part of a proposal providing many benefits, may help to inspire future investment. To be most useful, modelers may want to focus on characterizing confidence intervals associated with alternative land management scenarios, including extreme scenarios that can help champions explain the importance of the project.

Decision context 3 – Engaging potential participants:

What about participants? Do land managers and farmers use economic criteria when they decide to participate in a watershed management project? We found that participants consider many criteria, including how much they trust the program and their own desire to protect forests for their ecological value. We didn’t find evidence of formal monitoring or modeling influencing the decision to participate, but many participants told use about the importance of local observations of change. This is a great opportunity for modeling and monitoring studies to use participatory approaches, local knowledge, and locally defined goals.

Decision context 4 – Designing, siting, and implementing projects and activities

Watershed management programs need to identify what types of activities to do and where to put them. Hydrologic models potentially provide exactly the right information to make these decisions. Yet, we found that a mix of feasibility, legal definitions of effectiveness (e.g. the Brazilian Forest Code, which stipulates where forest protection should occur), and local perceptions of effectiveness are more important drivers of decisions than modeled outputs of potential impact. We interpret this to mean that super precise models of hydrologic benefits are less important than highlighting areas where various types of activities are most likely to generate consistent benefits, the places where uncertainty is the lowest. Providing this information can help to facilitate conversations around siting decisions, which will always include multiple factors.

Decision context 5 – Evaluating program success

Many watershed management stakeholders are interested in understanding what is “working” or not so they can makeappropriate adjustments. Scientists want to “get the science right” in watershed management, and that usually meansdeploying more monitoring equipment and running more sophisticated models. However, we heard over and over again that there was limmited money for installation and upkeep of monitoring equipment. As a result, data records were often incomplete in time and space and difficult to interpret. Investing in people who know the region and taking advantage of hydrologic data that do not require scientific insturments (e.g. observations of springs, pictures of water courses, records of water shortages from the municipality) may help to tell the story of change over time, and may be more practical and equally trusted in some locations. In addition, tracking non-water outcomes like social wellbeing and biodiversity that stakeholders care about may be equally important for evaluating success.

The bottom line

We use the framing of salience, credibility, and legitimacy to summarize our findings. Salience is about providing the content that decision-makers actually want. That means taking the time to talk with users, lots of them, before getting started. Credibility is all about how “right” the results need to be. One thing that stood out to us was that model outputs were often used to help to justify and facilitate conversations on key decisions. Thus, focusing too much on precision is often of limited value, but expressing uncertainty is key. And legitimacy is about whether people trust and will use the results, and that almost always about how the results are created and delivered, not about how precise they are. The most useful modeling studies will be co-developed with local stakeholders and will incorporate socio-economic and political realities into the modeling framework. Partnering with a strong local champion (s) who can help to ensure that modeling efforts focus on what is important to potential users and who can help deliver and communicate results in a compelling and relevant way is one very effective way to do this.

Leah Bremer PhD, University of Hawaiʻi Economic Research Organization and Water Resources Research Center

Kate Brauman PhD, Institute on the Environment, University of Minnesota