BLOG POSTS ARE PRELIMINARY MATERIALS CIRCULATED TO STIMULATE DISCUSSION AND CRITICAL COMMENT. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED ARE THOSE OF THE INDIVIDUAL AUTHORS. WHILE BLOG POSTS BENEFIT FROM ACTIVE UHERO DISCUSSION, THEY HAVE NOT UNDERGONE FORMAL ACADEMIC PEER REVIEW.

By James Mak

“Ua mau ke ea o ka aina i ka pono” [1]

In May 2000 the Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR) Division of State Parks began to charge $1 entrance fee per adult—tourist and local—who walked into the park to hike the iconic Diamond Head trail. A $5 entrance fee per non-commercial vehicle was added in January 2003. Commercial vehicles paid more, ranging from $10 to $40 per vehicle depending on passenger carrying capacity. The task of collecting the fees was contracted out to a private firm selected by competitive bid. Net proceeds from the fees (minus 20% to the Office of Hawaiian Affairs) were deposited in a special fund to pay operating expenses at Diamond Head and other parks in the State park system.

Fast forward to January 2020. DLNR had not raised the entrance fees at Diamond Head State Monument since they were first established in 2000. Since then, the general level of prices in Honolulu increased by 60 percent. Pre-COVID-19 pandemic annual attendance at Diamond Head is estimated at over 1 million. It is way past the time to raise those park fees.

The Division of State Parks manages 50 active State parks where visitors are welcomed. Diamond Head was the first State park to charge an entrance fee. (The City and County of Honolulu began charging entrance fees at Hanauma Bay Nature Preserve beginning July 1, 1995. [2]) Entrance/user fees were subsequently levied at several other high patronage State parks. Chapter 13-146-6, Hawaii Administrative Rules, adopted on September 11, 2015, established the fee structure at each State park for pedestrians, non-commercial vehicles, commercial vehicles, camping, and cabin and pavilion rentals. The entrance fees were the same as those at the Diamond Head State Monument with the important difference that residents also had to pay at Diamond Head but not at the other State parks (excluding Iolani Palace) that charge user fees. (Iolani Palace State Monument is administered by the Division of State Parks but is managed by the Friends of Iolani Palace—a non-profit organization– under a long term lease. It has a separate fee structure with discounts for residents.)

Like nearly all state and national parks in the U.S., Hawaii’s State parks are chronically underfunded even though what brings tourists to Hawaii, first and foremost, are its natural attractions. Hawaii Tourism Authority’s Hawaii Tourism Product Assessment study (1999) noted that “Hawaii’s unspoiled natural beauty is the foundation of Hawaii’s tourism product.” Yet, it is widely acknowledged that the amount of money the state government spends annually to protect the state’s natural resources is woefully inadequate.

According to Division of State Parks Administrator Curt Cottrell, the division operates on an annual operating budget of about $14 million with 80% of that going toward employee salaries and just $2.8 million for everything else like repairs, maintenance, and utilities. Cottrell notes that “…there is so much more that we can do than just clean toilets and empty rubbish bins, which is where we are.” Enforcement of park rules has been neglected; graffiti, illegal camping, vandalism and other forms of irresponsible behavior have become major problems. Deferred maintenance has reached $40 million. Efforts to persuade state lawmakers to provide more money haven’t been very successful. Cottrell argues that “…the only source left in terms of direct conduit of cash to improve the quality and services in our parks is to directly get it from the visitor coming into the park.” In other words, increase user fees on visitors. Most of the park visitors are non-resident tourists.

Cottrell’s rationale for raising park user fees suggests that it is the last option when other sources of funding are unavailable. It should be the first option. A fundamental rule of local public finance is the “Matching Principle”—those who benefit from public services (in this case State park services) should be matched with those who pay for the cost of the services. Thus, when it comes to levying charges for infrastructure use such as Hawaii’s State parks, the first rule is “whenever possible, charge.” [3] The application of this matching principle recognizes that tourists who visit Hawaii’s State parks are not the only beneficiaries of park use. Thus, fees levied on “direct” users are rightly supplemented by other state taxes, such as money from the State General Fund.

Hawaii’s state government is not alone in wanting to raise park user fees. The National Park Service raised entrance fees at Hawaii Volcanos National Park and Haleakala National Park (as well as at national parks across the country) beginning January 1, 2020. Entrance fees at both national parks are currently $30 per vehicle and $15 per pedestrian or bicyclist, good for 7 days at one park and 3 days at the other. The Honolulu City Council recently passed an ordinance raising the daily admission fee for out-of-state visitors at Hanauma Bay Nature Preserve from $7.50 to $12.

In October 2020, a much-needed increase in State park fees was signed into law by Governor David Ige and went into effect on October 9. The revised administrative rules contain several important differences from the previous rules. First, instead of establishing user fees for individual parks, it establishes fees by category of parks such as “state monument” (Diamond Head and Iao Valley), “state park” (Akaka Falls, Haena and Makena), “state recreational area” (Hapuna Beach), and “wilderness park” (Napili Coast). This makes it easier to extend user fees to other parks in the future. Second, residents no longer have to pay entrance fees at the Diamond Head State Monument. Residents still have to pay camping and cabin and pavilion rental fees at State parks where such services are available but at discounted rates. Third, a uniform entry and parking fee structure on out-of-state visitors (residents are exempt) is established at all 8 parks that levy user fees. For example, out-of-state park visitors will now pay $10 (instead of $5) “parking fee” per non-commercial vehicle, and $5 (instead of $1) “entrance fee” for walk-ins at 8 parks on 4 major islands. (The 2020 rules don’t clearly specify whether tourists who drive into the park must pay both the parking fee and the entrance fee; so far, if a visitor paid the parking fee, he/she isn’t required to pay the entrance fee. That may change in the future.) Higher fees are expected to raise an estimated $8.5 to $9 million in new revenue for the State parks system at pre-COVID-19 levels of park attendance.

The new structure of user fees isn’t based on economic principles found in text/reference books. [4] When asked: How were fees determined? State Parks Administrator Cottrell explained: “We just doubled everything.” [5] Moreover, to keep things simple, the parks administration decided to settle on a uniform fee structure for all parks rather than different prices at different parks depending on popularity and the cost of providing park services. Since the collection of fees at each park is separately put out to bid, Cottrell opined that it is a lot simpler to have uniform fees.

The main purpose of increasing park fees is to fix the current revenue short-fall, but it doesn’t mitigate the serious problem of congestion at some of our most popular parks. Instead of suggesting that people visit during off-peak times or visit less popular parks, a differentiated fee structure by location, time of day and travel season incentivizes people to do that on their own. [6]

Park user fees should be based on data and analytics and not on instinct. However, figuring out an efficient and fair fee structure isn’t easy. It requires detailed data on visitation (the Division of State Parks does not tally visitor counts at its fee charging parks) and quantitative analysis to ascertain visitor sensitivity to price changes at different locations, different times and different seasons. But for now, in the absence of having such information, and there has been no park fee adjustment for years, the Division of State Parks approach is understandable. Furthermore, the process has been transparent. In Hawaii, proposed fees must go through public hearings thus ensuring the actual fee structure has community approval and is politically acceptable to stakeholders.

The COVID-19 pandemic has upended the revenue plans of the Division of State Parks. Higher user fees mean nothing if tourism is shut down and parks are closed. State lawmakers are cutting budgets across executive departments. When parks reopen, visitors will have to pay higher fees but may not receive more services. That could exacerbate Hawaii’s image as an expensive place to visit. But not charging higher fees as visitors return in growing numbers will invite further degradation of some of the state’s most precious natural resources. That’s not a good outcome.

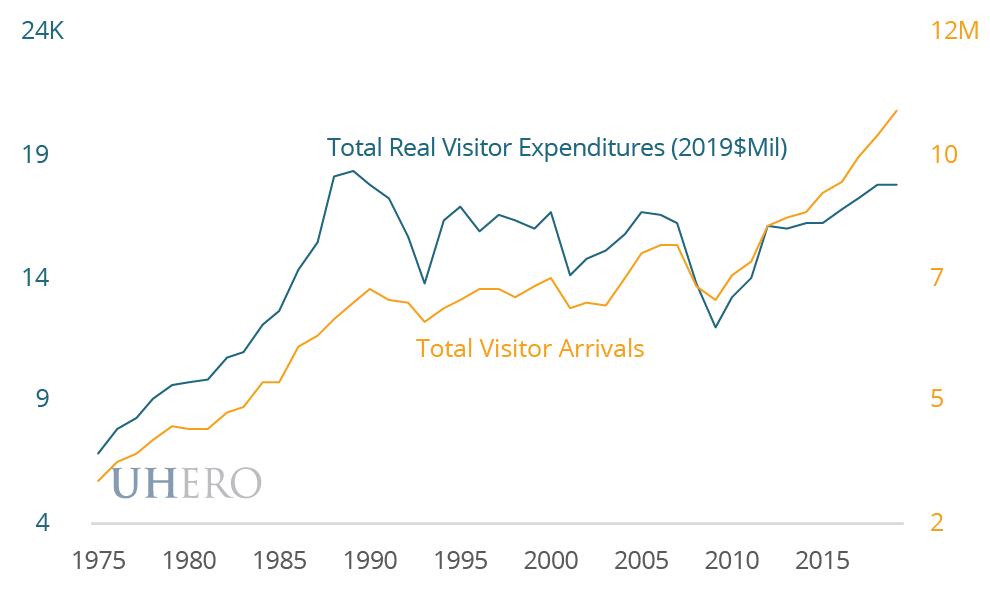

Nor is it likely that the new higher fees will deter large number of tourists from visiting Hawaii or abbreviate their stay. But even if some price sensitive visitors are discouraged from coming, that may not be such a bad thing as the number of visitors to Hawaii have increased by several million since 1989 (until COVID-19) while total tourist spending (in inflation adjusted dollars) has not. Hawaii could live with fewer lower-spending visitors.

A final observation. Privately owned tourist attractions set prices to maximize profits. Profit maximization is not the primary objective of publicly owned parks. Entrance fee policies at the latter typically involve recouping some of the cost of park operation while keeping attendance affordable to the public. Indeed, most Hawaii State public parks don’t charge entry fees as it is impractical to do so when the cost of collection could exceed the potential revenues collected. (That could change in the future with technology.) Hawaii’s State parks rely on user fees, State General Fund support, and the transient accommodation tax to meet expenses. Going forward, the State park system must also address management issues. A 2013 report by Margaret A. Walls (Resources for the Future) argues that, across the country, state park problems often go beyond money. Walls notes that some park management systems “seem to stifle creativity and innovation. Improving the financial viability of state park systems should be considered in the context of wider-ranging reforms.” [7]

The most obvious management reform needed to bring Hawaii’s State park system into the post-pandemic world is a coherent user fee policy—which activities should be funded by user charges and which should not be, and approximately what percent of operating expenses should be funded by user charges. Then, require frequent review of current user charges to determine if they need to be recalibrated.

Hawaii also needs to develop a smart technology plan to improve efficiency and reduce cost within the park system. Hawaii has been slow to adopt smart technology in resource/destination management.

Can and should the management model currently employed at Iolani Palace State Monument be used at a few other State parks?

At Haena State Park advance reservations are required for all vehicles, walk-in entry, and shuttle riders visiting the park, as well as for day visitors hiking the Kalalau Trail. If Haena State Park can use a reservation system to reduce congestion, why isn’t it employed at other high attendance State parks? Comparing best practices locally and elsewhere (but not only at public parks) is a good way to begin bringing improvements to the State park system.

[1] Hawaii State Motto: The Life of the Land is Perpetuated in Righteousness

[2] James Mak and James E. T. Moncur, “Political Economy of Protecting Unique Recreational Resources: Hanauma Bay, Hawaii,” Ambio, Vol. 27, No.3, May 1998, pp. 217-223.

[3] Roy Bahl and Richard M. Bird, Fiscal Decentralization and Local Finance in Developing Countries, Edward Elgar Publishing, 2018, p. 169.

[4] See John Loomis and Kreg Lindberg, “Pricing principles for natural and cultural attractions in tourism,” in Larry Dwyer and Peter Forsyth (eds.), International Handbook on the Economics of Tourism, Edward Elgar, 2006, pp. 173-187.

[5] Private phone conversation with Curt Cottrell on October 8, 2020.

[6] Loomis and Lindberg, (2006); Margaret A. Walls, “Protecting our National Parks: Changing the Structure of Entrance Fees Can Help, ” Resources, April 18, 2016 at https://www.resourcesmag.org/common-resources/protecting-our-national-parks-changing-the-structure-of-entrance-fees-can-help/

[7] Margaret Walls, Paying for State Parks, Evaluating Alternative Approaches for the 21st Century, Resources for the Future, January 2013. https://media.rff.org/archive/files/sharepoint/WorkImages/Download/RFF-Rpt-Walls-FinancingStateParks.pdf