BLOG POSTS ARE PRELIMINARY MATERIALS CIRCULATED TO STIMULATE DISCUSSION AND CRITICAL COMMENT. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED ARE THOSE OF THE INDIVIDUAL AUTHORS. WHILE BLOG POSTS BENEFIT FROM ACTIVE UHERO DISCUSSION, THEY HAVE NOT UNDERGONE FORMAL ACADEMIC PEER REVIEW.

How to Renovate Housing Policy in a Way that Works

On May 12, the University of Hawaii Better Tomorrow Speaker Series series hosted a discussion with Stanford economist Rebecca Diamond to address the crisis in housing supply and affordability. Below are some highlights from the conversation, which were condensed and edited for clarity. If you missed the event, you can watch the full Facebook live video here.

Let’s outline the scope of the problem, both in Hawai‘i and nationally. What metrics tell us that we’re in a bad place and where specifically are housing markets most troubled?

It’s not a surprise that we’re talking more about housing today than we were 30 or 40 years ago. That stems from the fact that the difference in affordability across space in the US has exploded. The most expensive city and the cheapest city were much closer in affordability in 1970, whereas now the difference between living in the Bay Area or Hawai‘i or New York is just astronomical compared to a small town in a rural part of the country. That divergence is keeping affordability on people’s minds because they can see other parts of the country that look a lot cheaper.

On top of that, we’ve had a slowdown in migration. People used to move across states and across counties at a much higher rate than they are today, and there are a variety of factors keeping people from wanting to move. But putting those facts together means that if you’re born into a part of the country and now it’s become expensive for a variety of external reasons, you’re really faced with this hard trade-off: Should I bite the bullet and move somewhere more affordable, or do I want to stay here with my community and the people and places I know? That’s the heart of the affordability matter. The combination of migration not being as desirable of an alternative and this huge difference across space.

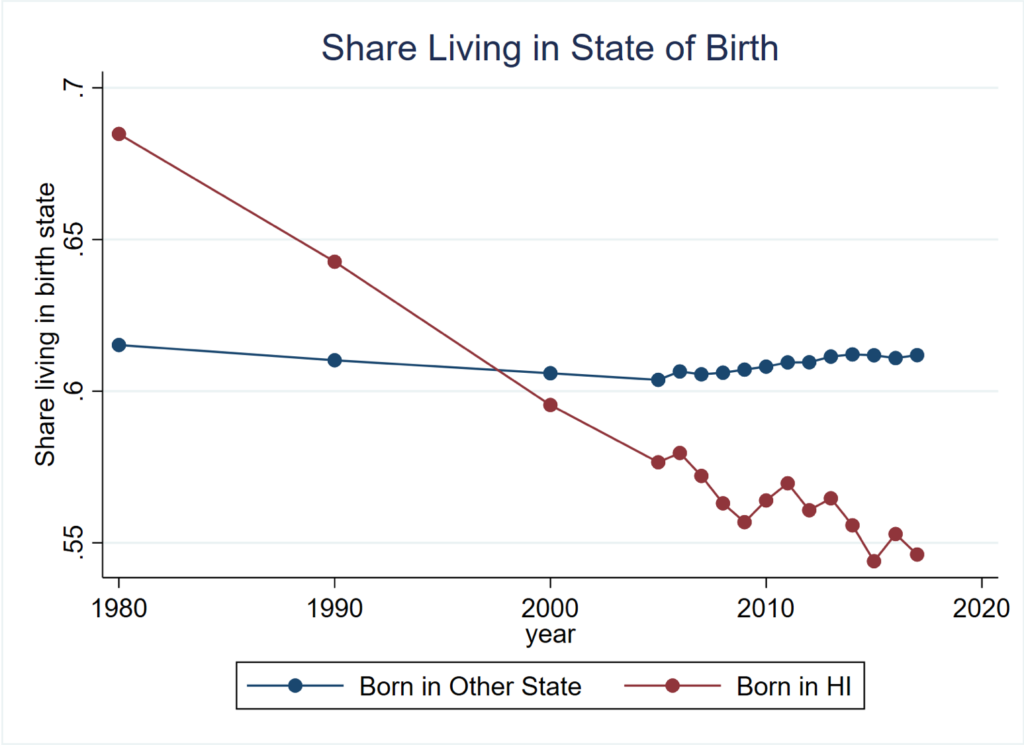

If you look at Hawai‘i, it’s a little bit of an outlier on some of these metrics. The first slide [Figure 1] shows what share of people are still living in their state of birth when they’re adults. The blue line is showing for every other state but Hawai‘i that’s been relatively stable over time. About 62 percent of people live in their state of birth, whereas Hawai‘i has gone through a big shift. In the 1980s, almost 70 percent of people born in Hawai‘i stayed there as an adult, where today that’s fallen to just over 55 percent. So there’s been this relatively large out migration of people that are initially born in Hawai‘i that we’re not seeing in the rest of the country.

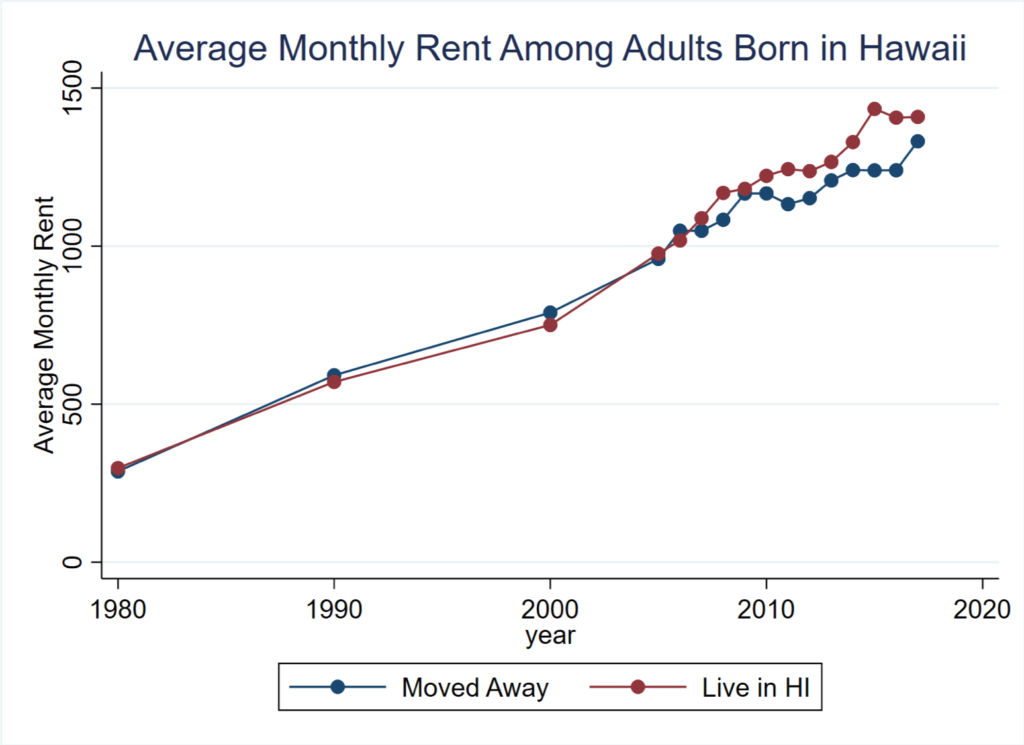

There could be many reasons pushing those initial residents out, but if you look at the graph [Figure 2], you can see the monthly rent of people that choose to stay in Hawai‘i are paying versus the people that are from Hawai‘i but move away. You can see more recently this gap opening up, where the people that move away are now paying about 10 or 15 percent lower monthly rent wherever they live in the rest of the country than the people that choose to stay in Hawai‘i. Maybe in 1980 and 1990 that out-migration wasn’t so much about affordability, but today the out-migration suggests that they’re looking for a more affordable place to live.

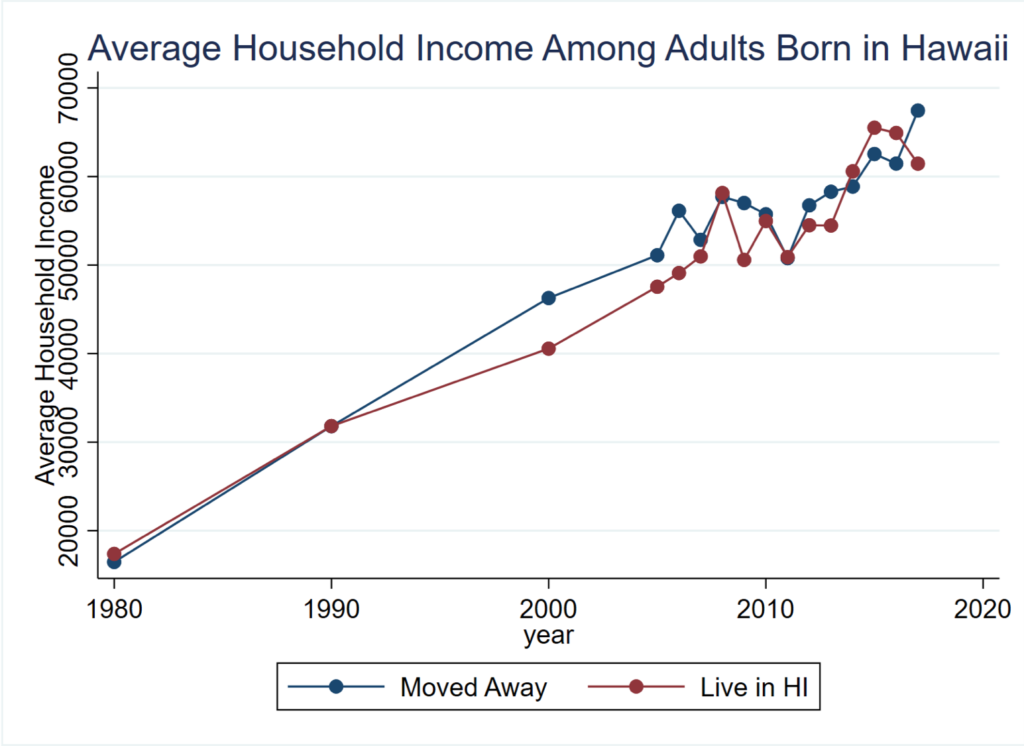

It seems more about affordability as opposed to local labor market conditions. The graph [Figure 3] compares the incomes of people that were initially born in Hawai‘i between the ones that stay in Hawai‘i versus the ones that move away. It looks like the labor market opportunities are similar for the people that stay versus move away, but those that move away are able to find more affordable housing. Affordability in Hawai‘i seems like an increasingly strong force, and it could be contributing to some of this out-migration of people that initially grew up in Hawai‘i but live somewhere else. I think this highlights that Hawai‘i is facing a strong housing affordability crunch.

Given all the talk about supply shortages, what is the role for supply-side programs and other forms of development subsidies?

I think supply-side subsidies set up in the right way could be very effective. Right now, we have a lot of supply-side subsidies such as project-based Section 8 or the low-income housing tax credit, which target specific buildings deemed eligible to get access to these funds. Other buildings fit the statutory criteria, but there are just not enough funds to go around.

Because we have mismatch in the market potentially willing to supply buildings – versus the government funds not able to cover all the developers that would be willing to take up this subsidy – means you can have this crowd-out effect. I’m going to subsidize this one building, but then the building across the street doesn’t get that subsidy. The building across the street then has to respond and compete with the rents that are subsidized. And you can end up undoing the subsidy, because you only help certain buildings, and the private market has to equilibrate to those incentives.

If you had an incentive that was more broad-based, which said anyone who builds a building that has rents below x – where x is some affordable level – then you wouldn’t be targeting a few buildings. You would say to anyone who can satisfy these rules, “we’re going to give you this subsidy.” That’s going to increase total supply as opposed to picking and choosing which buildings we’re going to help.

Policies that can list a set of criteria – if you can get your rent under this x level that we decide is the cut off, we’re going to help you out and either subsidize your construction or maybe we’ll ease some of the land use restrictions that you would normally have to satisfy – could push developers to be able to pencil out the revenues and costs of building and get the total supply to go up.

One seemingly simple policy is rent control, but your research suggests this doesn’t work very well. Why not?

Rent control usually means that when a tenant moves into a rental property the initial upfront rent is not regulated. There’s just a cap on how much the rent can go up if the tenant were to remain in the property. It’s like a kind of insurance. It says if you can afford it now, you’re going to be able to afford it going forward. You’re not going to get gentrified out of your neighborhood. This is insurance against displacement due to housing affordability. I think there’s a lot to like about that type of setup.

The issue with rent control is that this subsidy toward your rental price is essentially fully coming out of your landlord’s pocket. We’re not sharing the cost burden of this subsidy across broader society. Owner-occupied homeowners are not contributing to that cost; it’s fully on the landlord.

We looked at a law change in the mid-90s in San Francisco that expanded rent control eligibility based on the year that your property was built. We compare people that were already living in properties built in the 1970s, which got access to rent control, versus properties built in the 1980s, which didn’t get access to rent control. It creates this nice experiment for us where we can compare what happens to the properties suddenly covered by rent control versus the ones that didn’t get access.

The initial results look pretty promising for rent control. The tenants that are living there at the time of rent control expansion show lower levels of displacement from the city and have lower mobility rates in general. They seem to really value that rent control. It helps them a lot mostly because rents are cheaper, and that makes cost burdens and the rest of your life a little easier.

When we follow this policy over the longer term, landlords are not silly – they’re trying to make ends meet themselves – and because this huge subsidy is coming right out of their pockets, they start to supply their real estate to other uses. We see a lot of conversion to owner-occupied housing, because they can get the full value of their real estate. We see a decline in the supply of rentals.

Basically, over the long run, this initial benefit to the initial tenants is fully undone, because the supply of rental housing goes down so dramatically. We find it declines by about 20 percent. That pushes up those upfront rental prices so much that the future tenants are not going to benefit. Even though they get this guarantee that the rents are not going to go up, they’re paying more money up front than they would have.

What rent control does is it benefits the tenants that live there when the law changes at the expense of the future tenants that will live there in 10 or 20 years. It’s a little bit like a Ponzi scheme. You’re stealing money from future people, because they don’t get to vote in the election about whether we have rent control, and you’re benefiting the current tenants.

You could think of it as a Band-Aid. Maybe it’s not going to ruin the housing market overnight, but 5, 10, 20 years later it’s really going to cause even further supply shortages and make affordability even worse.

We might want to supply some kind of insurance against getting displaced from your neighborhood but having the landlords to pay that full tax – putting the burden on this narrow set of the population – suggests that maybe there are other ways to raise that revenue. A broader property tax where everybody chips in a little bit, as opposed to just landlords, might be a more efficient way to produce those subsidies.

Do you have any thoughts on inclusionary zoning?

Inclusionary zoning is the hot new affordable housing policy out there in a lot of the expensive cities in the US and also around the world. It’s one of the things I want to study in my research. We don’t have a lot of systematic clear evidence about how to run this policy.

To give a little description of what this is, it is forcing developers that build market-rate housing to set aside a share of their apartments to be rented at below-market rates to income-eligible tenants. So, maybe there’s a new luxury apartment building going up in your neighborhood, 10, 20 percent of those units, depending on which part of the country you’re in, are going to be set aside and rented at below-market rates.

The policy is new, so most affordable housing is not inclusionary zoning, because most housing is old housing in the US. Even the new construction that we have had, only 10 percent of it is inclusionary zoning. In a magnitude sense, this is just a trivial part of the affordable housing market out there relative to the low-income housing tax credit or market rate housing that is affordable in certain parts of the country.

The way to think about inclusionary zoning is it’s really this trade-off with taxing developers in exchange for reallocating some of these units to the low-income population. Getting that tax right is super important, and we just don’t know much about it. Should we be setting aside two percent of these units to be affordable? Should we be setting aside 40 percent of these units to be affordable?

The bigger the tax – the bigger the share that we force to be set aside – the bigger the tax on the developer is to build housing. Obviously, if we taxed 100 percent of those units to be affordable, no developer would ever choose to build, because you would lose money. There would be no way to cover your construction costs. But if we set aside zero percent of those units, not many housing units would get distributed to the low income. So, the question is, what number should that be?

In different parts of the country, you see that number all over the place, and it’s been going up over time. In the Bay Area this number is going up, in Boston it’s going up, in New York it’s going up. I’ve talked to a number of developers here that say the current number in San Jose, California is so high that unless rents can go up a lot more, we can’t cover our costs. Even these super-expensive rents that San Jose already has are not high enough for the developer to cover their costs to build.

We have to think hard about what’s the right trade-off. It’s taxation versus redistribution. If you tax incomes too much, people won’t supply their labor, but we do need redistribution. I would love to know if that number should be two percent, 10 percent, 15 percent. It’s something I’m working on myself, but I don’t have an answer yet.

You’ve written a bit about housing elasticity – the ability of a market to respond to increased demand by building new housing. I’m wondering if you could outline some of the consequences of that that you see in your work and also what types of reforms could be or have been successful in that regard?

There are two big factors that affect housing supply elasticity. One is land for development, which, if you’re surrounded by ocean, is just not going to be developable land, and the other is a more flexible one, which is land-use regulation.

Hawai‘i has one unique feature about it which I think could add to this margin of housing supply elasticity: you’re a tourist destination. Should this land be supplied to local residents or should it be supplied to the tourism industry? Potentially one thing that might be elastic in Hawai‘i in regards to housing supply is reallocating properties between the tourism market and toward the local long-term resident population.

Airbnb pushes things in the other direction. It’s an easy way to turn long-term rentals into short-term vacation rentals. But even before Airbnb, second homes of people living in other parts of the country were a non-trivial share of the Hawai‘i housing market.

Finding ways to tax the properties that are allocated toward the tourism market as a way to raise revenue that can then be redistributed to Hawai‘i residents – but also as an incentive mechanism to push properties back to the long-term rental market – can be one mechanism where there actually is some supply elasticity.

You’re not going to get more land, but policies that can directly increase property taxes for short-term rentals or vacant properties can be a way to push housing back in that the long-term resident direction.