BLOG POSTS ARE PRELIMINARY MATERIALS CIRCULATED TO STIMULATE DISCUSSION AND CRITICAL COMMENT. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED ARE THOSE OF THE INDIVIDUAL AUTHORS. WHILE BLOG POSTS BENEFIT FROM ACTIVE UHERO DISCUSSION, THEY HAVE NOT UNDERGONE FORMAL ACADEMIC PEER REVIEW.

By Leah Bremer, Makena Coffman, Alisha Summers, Lisa Kelley, and Billy Kinney

“That whole experience of bonding, the family, the fresh air, that’s so critical. And we’ve lost a lot of that. As we lose the beaches, we lose that part of our culture, which is Hawaiʻi’s culture. Whether it’s a barbecue… or spend [ing] the whole day at the beach … that’s a beautiful, healing, bonding thing for families and communities. We’re losing that because the beaches are disappearing.”

– Government representative involved in coastal management

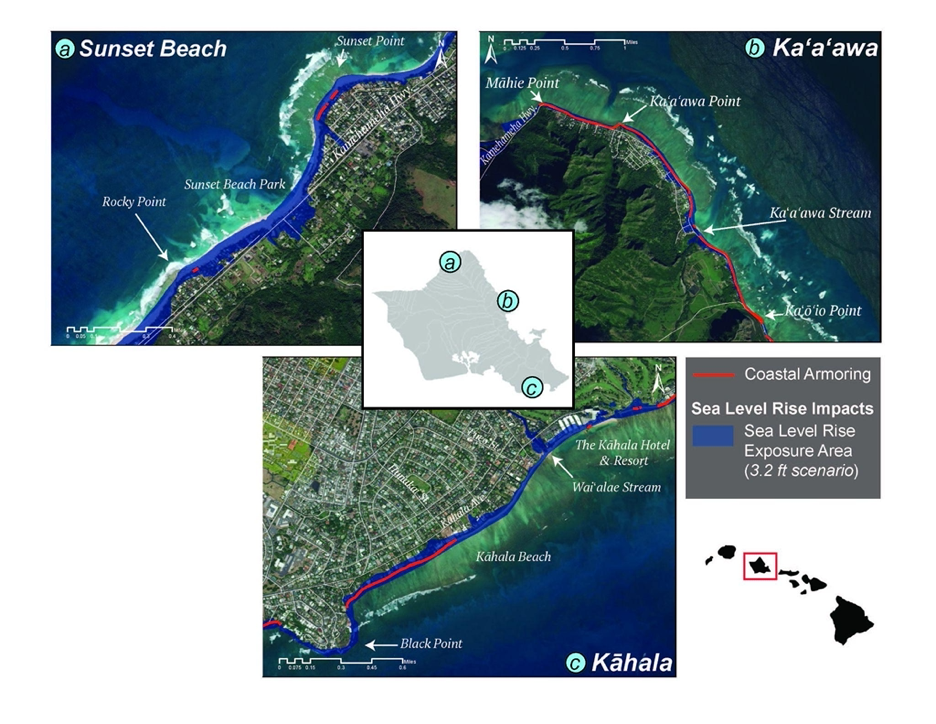

Beaches are central to Hawaiʻi’s ecology, culture, and economy. Yet, these places are increasingly threatened by elevated coastal erosion under coastal hardening (e.g. sea wells) and sea level rise. Hard decisions on how and when to adapt-in-place or retreat, require understanding the diverse ways that beaches and coastline matter to people in Hawaiʻi and how various responses influence these uses and values. As part of a National Science Foundation, Coastlines and People (COPE) grant, our interdisciplinary team interviewed and surveyed 42 civil society, government, and the private sector representatives involved in coastal decision making in Hawaiʻi. [1] We grounded our conversations around three distinct coastal areas on Oʻahu: Kāhala, Kaʻaʻawa, and Sunset Beach (See locations and photos of sites in Figures 1-4 below). This blog summarizes some high level take homes from our recent publication in Ocean and Coastal Management.

Figure 1: (a) Sunset Beach, (b) Kaʻaʻawa, and (c) Kāhala study sites. Expected inundation from 1- meter of SLR is shown in blue and known existing coastal armoring (i.e. seawalls) as red lines. Flood exposure is still likely in areas with seawalls (Habel et al., 2020). Data Sources: Amaya et al. (2021), Hawaiʻi Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation Commission (2021).

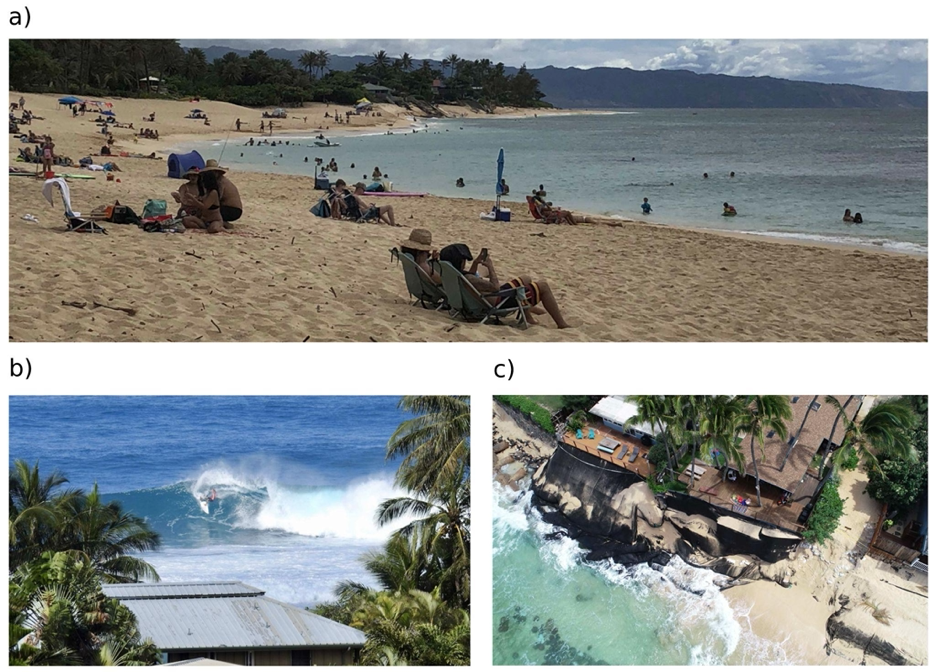

Figure 2: Images of Sunset Beach showing (a) the beach during the calmer summer months which is popular for recreational swimming and sunbathing (photo credit: authors); (b) the world-renowned surf break with a surfer on a winter swell wave (photo credit: Aaron Ungerleider 2020); c) areas with extreme erosion where geo- textile materials hold sand in place and protect homes. The beach when experiencing episodic beach loss is often difficult or impossible to traverse and creates discontinuity of the shoreline (photo credit: Dr. Shellie Habel – University of Hawaiʻi Sea Grant 2021).

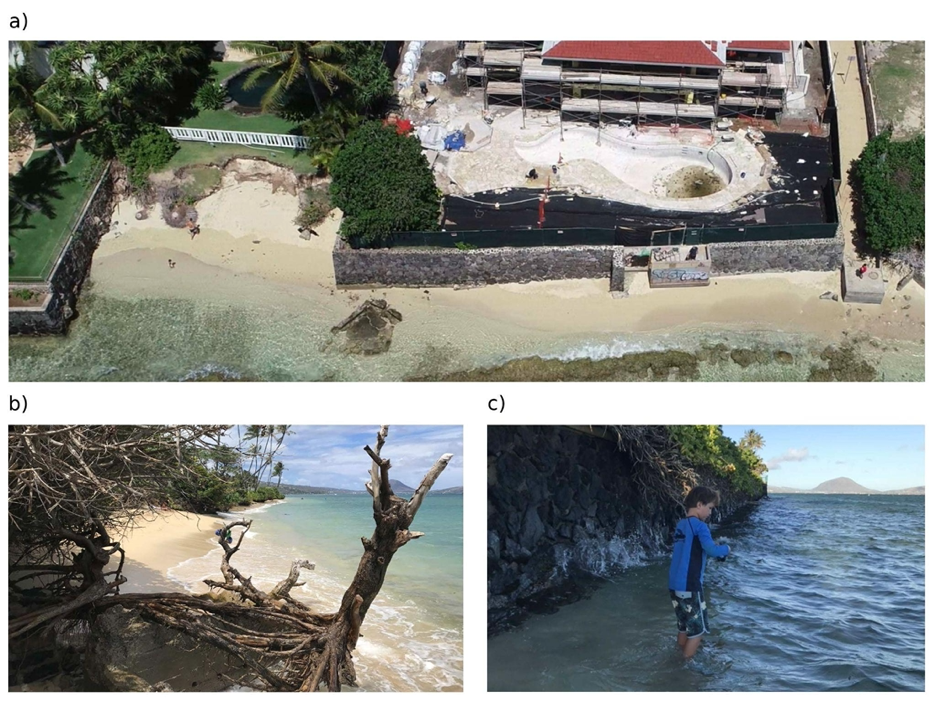

Figure. 3. Images of Kaʻaʻawa showing: (a) pocket beach with a family swimming in the nearshore, adjacent to the coastal highway and its protective revetment; (b) beach park seawall where the sandy beach has disappeared; and (c) even without a sandy beach, the park is still a place where family and friends camp and gather (photo credits: authors).

Figure 4. Images of Kāhala beach showing: (a) a person on a pocket beach surrounded by seawalls on both sides (photo credit: Dr. Shellie Habel – University of Hawai’i Sea Grant 2021); (b) a thick vegetation line and a City stormwater outlet in disrepair with inundation, making it difficult to access the beach from the right-of-way (photo credit: Nori Tarui 2020); and (c) child walking out for a swim in an area where there is no longer a sandy beach, even during low tide (photo credit: authors, child of second author).

Our recent article published in Ocean and Coastal Management addresses three main questions based on our interviews with civil society, government, and private sector representatives:

(i) What uses and values regarding beaches and coastlines do government, private, and civil society actors identify as currently important for coastal communities and stakeholders?;

(ii) Which uses and values do these actors see as ideally shaping decision-making around SLR adaptation?; and

(iii) What conflicts are emerging in relation to how SLR (and SLR response) is impacting decision-making regarding such uses and values? .

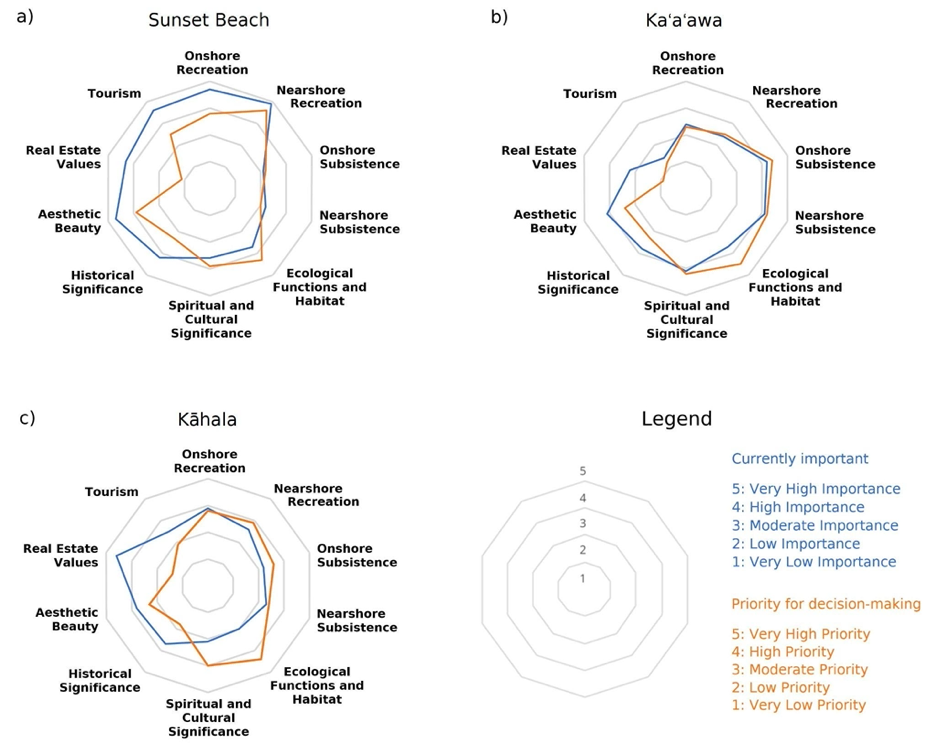

Figure 5 shows spider diagrams of the results of our pre-interview survey. With spider diagrams, the higher the ranking, the larger the area is around that value. We first asked respondents to rate their perception of the current importance of various uses and values for each study site (shown in blue in the spider diagrams below). We then asked for perceptions on how these uses and values should ideally be prioritized in decision making around sea level rise.

We provide some high level takeaways below.

First, the current uses and values of coastlines (in blue) are site specific (i.e. place-based). For example, nearshore recreation was rated as the most important value of Sunset Beach, onshore subsistence the most important for Kaʻaʻawa, and real estate value the most important for Kāhala. While this may not be surprising, explicit acknowledgement of this helps to inform policy.

However, when it comes to what respondents think should ideally be prioritized in decision making (in orange), respondents, on average, push ecological functions, habitat, spiritual and cultural values to the top in all sites. In contrast, real estate value was given the lowest priority across all sites, including for Kāhala. Other important uses and values seen as important to prioritize varied by place. For example, nearshore recreation is seen as important in Sunset Beach given its importance as a world-famous surfing destination. In Kaʻaʻawa, subsistence activities by local communities, such as limu gathering and fishing, are ranked as highly important to protect.

Figure 5: Perceptions of what is currently considered important (blue) versus what interviewees perceive should be ideally prioritized in decision-making (orange) in (a) Sunset Beach, (b) Kaʻaʻawa, and (c) Kāhala.

The links between the ecological value of beaches and community and economic health are captured by a quote by a private sector interviewee: “If our ʻāina isn’t thriving, we’re not going to thrive as a community and as people. If we’re not doing those two things first, we’re not an appealing visitor destination.” Likewise, a civil society representative noted the connections between ecological value and subsistence: “We have to understand, and again this is partly how I was raised, that our oceans are a refrigerator first. And our ability to access them and to feed and sustain ourselves is right up there. And tied to that obviously is the ecology.”

Interestingly, what emerged in interviews with respondents who ranked real estate as a high priority is that they do not see a tradeoff between the broader ecological and societal values of beaches and the private property values. This is in stark contrast to the majority of interviewees who emphasized that it really is all about tradeoffs and that protecting the societal value of beaches will ultimately require retreat from the coast. This inherent conflict between broader societal values of beaches and private real estate values was particularly stark in Sunset Beach.

Another important theme that emerged relates not just to “what” values, but “whose values.” There was a strong sense by many interviewees that Native Hawaiian families with ancestral knowledge connections-to-place need to be more deeply included in decision-making. In the words of a non-profit conservation organization representative: “Those who live there, those who have ties there, those who go back generations there hold the strongest voice.”

This publication explored the diverse uses and values of beaches and coastlines from the perspective of civil society, private sector, and government representatives involved with coastal decision making on Oʻahu. This publication is part of a larger project on coastal management in the face of accelerated SLR.

1 Due to limitations brought by the global pandemic, we were not able to extensively interview residents and local community members as our research team had originally planned. This will be an important area of future research.