By Sumner La Croix

Single-family home prices in Honolulu soared to record highs in 2015, with the median price for the full year reaching $700,000. In the second quarter of 2015, only three U.S. cities had higher prices—San Jose-Sunnyvale-Santa Clara ($980,000), San Francisco-Oakland ($842,000), and Anaheim- Santa Ana-Irvine ($713,000)—and Honolulu’s price premium over the next highest city—San Diego ($548,000) is huge. High housing prices are, however, nothing new for Honolulu or the State of Hawaii. Census data show that home prices in Hawaii in 1950 were already higher than in the 48 mainland states. Honolulu’s long history of high land and housing prices relative to the U.S. mainland tells us that any explanations of high land and housing prices must be rooted in history to be valid. In my new UHERO report on land and housing markets in Honolulu, I identify four factors that have contributed to high housing prices in Honolulu over the last 50 years.

The first factor is somewhat obvious but perhaps the most important—Hawaii’s world-class amenities. Media and consulting firm surveys regularly place Honolulu among the top cities for quality of life. Consider the following attributes which are likely to positively affect the Honolulu price: warm ocean waters; high number of sun days, moderate temperatures, trades winds; a multi-cultural and multi-ethnic social environment, highlighted by the host Native Hawaiian culture; relatively low racial and ethnic tensions; and a low crime rate. To gain access to these positive environmental attributes, Honolulu residents compete with each other and with people living outside Hawaii to pay higher housing prices and to accept lower wages.

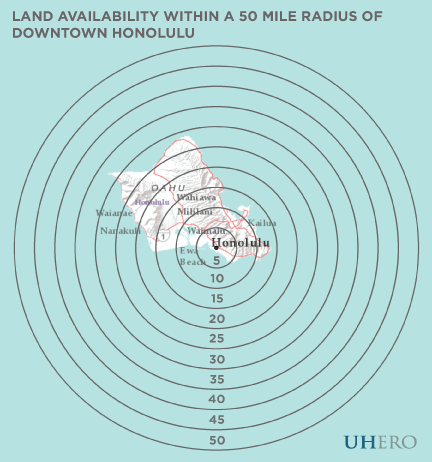

A second factor raising housing prices is that the competition to live in paradise is exacerbated by the population being concentrated in the smallest natural supply of land available in any U.S. metropolitan area. Honolulu has a very small natural supply of developable land, with roughly 92 percent of the 50-kilometre radius circle centered on the Honolulu downtown not developable, either being mountains, wetlands, lakes, harbors, or the Pacific Ocean. This is much higher than the 80 percent measure of undevelopable land for the next most constrained U.S. metropolitan area, Ventura, California, or the 63 percent in San Diego or the 40 percent in New York City. High rents in the central city that middleincome residents could normally escape by moving to a distant suburb would leave a Honolulu family paddling a canoe in the middle of the Moloka‘i Channel.

A third factor is land use regulation. The process of competition in Honolulu land and housing markets takes place under the watchful eyes of state and county governments that together impose the most severe regulation on land development to be found in any large U.S. metropolitan area. We compare Honolulu’s regulation with other U.S. cities by examining values of the Wharton Residential Land Use Regulatory Index, a respected index measuring land use regulation in U.S. cities. Developed by economists Joseph Gyourko, Albert Saiz, and Anita Summers, the Wharton Index aggregates 11 sub-indexes: a local political pressure index, a state political involvement index, a state court involvement index, a local zoning approval index, a local project approval index, a local assembly index, a supply restrictions index, a density restrictions index, an open space index, an exactions index, and an approval delay index. Honolulu has a higher value of the Wharton Index (compiled in 2006) than any other US metropolitan area. Its high score stems from the multiple layers of rigorous, lengthy review by both state and county governments for all new development projects.

A fourth factor that might be helping to keep Honolulu’s housing prices high is the “home voter” hypothesis, an idea first developed by the urban economist William Fischel in 2001. The idea is that high housing prices induce homeowners to vote for city and county officials who support regulations on residential development and to lobby against more development in their neighborhoods. This feedback effect from high home prices to even higher levels of regulation serves to maintain housing prices at elevated levels and protect home owners’ wealth. The economist Albert Saiz has found some empirical support for the home voter hypothesis in the overall U.S. sample. No direct evidence for the home voter hypothesis exists for Honolulu. Qualitative evidence is more abundant, as virtually any proposed new housing project or extensive redevelopment have encountered opposition in the courts, neighborhood, the Hawaii State Land Use Commission, or the Honolulu City Council.

BLOG POSTS ARE PRELIMINARY MATERIALS CIRCULATED TO STIMULATE DISCUSSION AND CRITICAL COMMENT. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED ARE THOSE OF THE INDIVIDUAL AUTHORS. WHILE BLOG POSTS BENEFIT FROM ACTIVE UHERO DISCUSSION, THEY HAVE NOT UNDERGONE FORMAL ACADEMIC PEER REVIEW.