The following post is excerpted from UHERO’s Brief “Should we increase Hawaii’s minimum wage?”

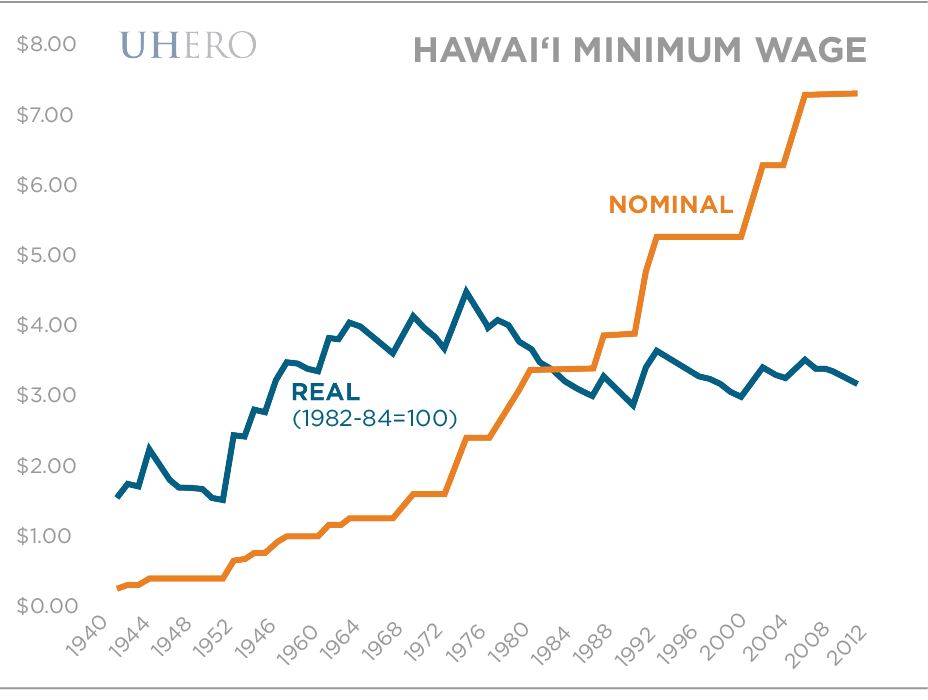

Raising the minimum wage may be one of the hottest issues of this years’ legislative session. Two bills have been introduced to increase the minimum wage and both bills also propose indexing the minimum wage so that it is adjusted for future inflation. President Obama made a similar proposal, to increase the federal minimum wage from $7.25 to $9 and index it for inflation, in his 2013 State of the Union speech earlier this month.

According to proponents, raising Hawaii’s minimum wage is necessary to help the working poor. However, as an antipoverty tool the minimum wage is undoubtedly inefficient. There is surprisingly little correlation between a worker earning the minimum wage and living in poverty (Charles Brown, 1988). Approximately one third of the minimum wage workers in the U.S. are teenagers and not heads of households. Furthermore, most teenagers earning below the minimum wage are not members of poor families. All but one recent study have found that past minimum wage hikes had no effect on poverty.1 These studies also find no evidence that past minimum wage increases have significantly reduced poverty. Only if a larger proportion of Hawaii minimum wage earners are members of poor households will raising the minimum wage prove successful in improving living standards here.

An obvious question is whether there is a better way to raise the incomes of low-income workers, one that does not raise these concerns. In fact there is: the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). The EITC is a refundable federal income tax credit for low to moderate income working individuals and families. Congress originally approved the tax credit legislation in 1975 in part to offset the burden of social security taxes and to provide an incentive to work. When the EITC exceeds the amount of taxes owed, it results in a tax refund to those who claim and qualify for the credit.

According to a 2007 study by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), an increase in the minimum wage to $7.25, as was eventually passed that year, would increase wages by $11 billion, of which $1.6 billion would go to poor families. Increasing the EITC for large families and for single people would cost $2.4 billion, of which $1.4 billion would go to poor families! The EITC does not directly raise labor costs to businesses, so it does not reduce the demand for unskilled workers. As a result, welfare recipients may be able to find jobs, gain job experience, and go on to earn higher wages as they accumulate skills.

So why increase the minimum wage when an increase in the EITC is a more effective way to eliminate poverty? Clearly in today’s environment of fiscal austerity, increased spending to fight poverty has little chance of getting through Congress. And, the EITC, like many government programs, has very high administrative costs. The minimum wage, on the other hand, has practically no administrative costs. Finally, policy makers may see raising the minimum wage as an important symbolic gesture of support to working families. No wonder the minimum wage is a popular tool among policy makers.

– Sang Hyop Lee, Carl Bonham, Atsushi Shibata

1 The one exception is Addison and Blackburn (1999), who find that minimum wage increases reduce poverty among junior high school dropouts. However, as Neumark and Wascher (2008) note, junior high school dropouts are older and unlikely to have small children; whereas most antipoverty efforts focus on families with younger children.