By Tim Halliday

Our work indicates that a bad economy can kill you.

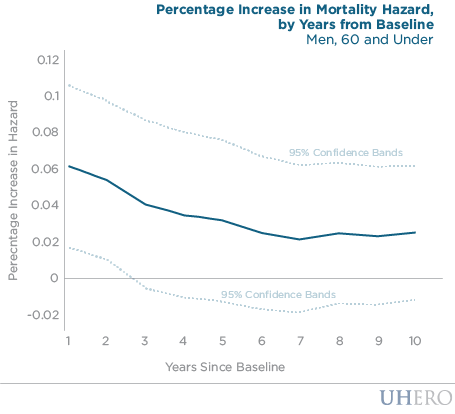

Specifically, we show that over the ten years from 1984 to 1993 that a one-percentage point rise in the unemployment rate increased the risk of dying within the subsequent year by 6% for working-aged men. This translates to roughly 24 more deaths per 100,000 people. A percentage point increase in the unemployment rate increases the number of unemployed by about 1.5 million, resulting in about 360 additional deaths of men between the ages of 30 and 60. Of note is that we find no such relationship for women or the elderly who tend to have weaker ties to the labor market.

Social scientists have long been concerned with the health consequences of business cycle fluctuations and, more generally, changes to one’s socioeconomic status. If public health tends to decline when the economy performs poorly then the costs of recessions are not limited to purely economic hardships such as unemployment and underemployment. Indeed, early work on the topic by Harvey Brenner, a public health researcher at the University of North Texas and Johns Hopkins University, suggested that mortality rates did tend to rise as the economy worsened. This work appears to indicate that poor job market prospects come with increased stressors that pose health hazards.

Subsequent work challenged these findings. Christopher Ruhm, a health economist at the University of Virginia, raised numerous methodological issues with the earlier studies and showed that once these were addressed mortality rates actually declined during recessions. This ushered in an era of work by health economists investigating if recessions were, in fact good for your health. The explanation for this counter-intuitive result was that people tended to lead healthier lifestyles during recessions. Recessions created more time for people to look after themselves and participate in health activities. Having less money also made people less likely to purchase harmful vices.

However, more recent work supports the earlier idea that recessions have a negative impact on public health. For example, research by Till von Wachter and Daniel Sullivan, economists at UCLA and the Chicago Fed, looked at micro-data from Pennsylvania and showed that involuntary job displacements during the early Eighties were associated with much higher mortality risks. Other work by researchers at UC Davis replicated Ruhm’s findings but showed that mortality rates also declined for the elderly and the young. Since those groups should have weaker labor force attachments, this research cast doubt on the healthy living mechanism.

So, what explains the difference between our finding and Ruhm’s? In principle, both of our studies should be identifying the same parameter and so should deliver the same or, at least, similar estimates. However, the one key difference is that our study uses data that are at the individual level, whereas other work uses data that are at the state level. This is noteworthy because higher levels of aggregation have been known to induce biases in primitive relationships that exist for individuals. Our paper argues that this use of individual data supports the case for the negative relationship between recessions and health.

While our work cannot tease out the mechanisms that generated our findings, we can offer some speculation. We believe the relationship between stress under poorer macroeconomic conditions and the risk of dying from cardiovascular-related causes may be a viable mechanism worthy of future investigation.

BLOG POSTS ARE PRELIMINARY MATERIALS CIRCULATED TO STIMULATE DISCUSSION AND CRITICAL COMMENT. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED ARE THOSE OF THE INDIVIDUAL AUTHORS. WHILE BLOG POSTS BENEFIT FROM ACTIVE UHERO DISCUSSION, THEY HAVE NOT UNDERGONE FORMAL ACADEMIC PEER REVIEW.