At the start of the first post-sequester week, economists at the annual policy conference of the National Association for Business Economics (NABE) in Washington D.C. debated options for U.S. fiscal policy. Two leading figures from the right and the left took starkly different views of where policy should head in the near term, but agreed on (at least some) longer-term directions.

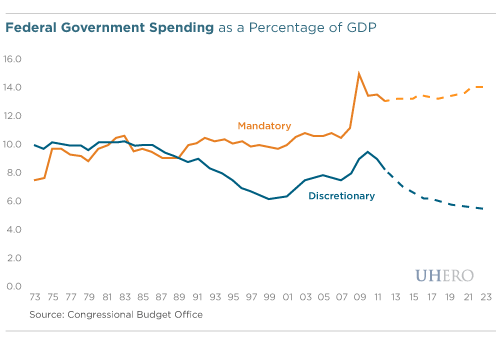

Conservative economist John Taylor argued for what he calls a “pro-growth” package of federal spending reductions that would bring the share of spending relative to the size of the economy down several percentage points over the next few years. He pointed out that similar reductions accomplished in the 1990s under Bill Clinton were accompanied by strong economic growth.

Former Clinton economic advisor Laura D. Tyson countered that in fact more government spending is needed in the near term, targeted toward investments in infrastructure and related areas that are key to future growth. In her view, high unemployment represents a “pure waste” of productive resources today, the result of inadequate aggregate demand in what has been a painfully slow economic recovery.

We find more to agree with in Tyson’s argument. While there is a fairly broad agreement that government debt burdens the economy in the long run (more on this in a minute), it is hard to buy Taylor’s argument that cutbacks will so improve business confidence that they will boost activity. In fact, we know that fiscal expansion can be particularly powerful in times like the present with large quantities of unused resources. And like Tyson, we are concerned that failure to address the current high rates of long-term unemployment risks persistent damage to growth prospects going forward. Now more spending is a nonstarter in the current environment. But we do think this argues for as much caution as possible when considering how rapidly to cut spending from current levels. Especially if the cuts are indiscriminate sequester-style slashing that hits all areas of spending without regard to their relative importance or impact.

Not surprisingly, the two economists also staked out different philosophical positions on the appropriate size of government. Taylor emphasized the manner in which government can crowd out private activity, and so advocated downsizing to historical averages. Tyson asked what makes 20% special, and she made the case for public investments, particularly in education, that could pay big dividends.

So where do the two camps agree? On the need now for clear plans to address the burgeoning federal debt in the long-term, since failure to do so creates uncertainties that hinder private investment. Not to mention the unknown potential for a debt crisis further down the road. Tyson called for a credible long-term deficit reduction plan as soon as “politically feasible.” Given the Beltway dysfunction of the past several years, even this economists’ consensus view seems like a tall order.

– Byron Gangnes