BLOG POSTS ARE PRELIMINARY MATERIALS CIRCULATED TO STIMULATE DISCUSSION AND CRITICAL COMMENT. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED ARE THOSE OF THE INDIVIDUAL AUTHORS. WHILE BLOG POSTS BENEFIT FROM ACTIVE UHERO DISCUSSION, THEY HAVE NOT UNDERGONE FORMAL ACADEMIC PEER REVIEW.

By Dylan Moore and Nate Hix (Hawaiʻi Public Health Institute)

In Hawaiʻi, as in other states, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)—otherwise known as food stamps—is one of the largest welfare programs available to low-income residents. Currently, a family of four can receive as much as $1,759/month in SNAP benefits. In a typical month, the total value of SNAP benefits in Hawaiʻi exceeds $60 million.[1]

Given that these generous benefits are paid for entirely by the federal government, it is not surprising that the SNAP eligibility criteria have always been largely controlled at the federal level. However, following changes to the program in 2000, states were given greater latitude to tweak some of the eligibility rules by establishing a program of “broad-based categorical eligibility” (BBCE). For example, through BBCE, states were able to eliminate asset limits, which prevented households with high savings from receiving SNAP benefits.[2] BBCE also allows states to raise limits on the amount of income households can receive and still qualify for SNAP.[3]

Since October 2010, Hawaiʻi—like the majority of states—has established a BBCE program. For the vast majority of Hawaiʻi residents, this resulted in the elimination of SNAP asset limits as well as a higher “gross income limit”. The latter change ensures that Hawaiʻi households with a total income as high as twice the federal poverty line may still qualify for SNAP.[4]

However, Hawaiʻi’s BBCE program did not eliminate another crucial income limit: the “net income limit”. Net income in the SNAP program is defined as total monthly household income after deducting certain non-food household expenses like rent, utilities, medical costs, childcare costs, and others. Before BBCE, households needed to have a net income below the federal poverty line to qualify for SNAP benefits (in addition to meeting the gross income limit). But states are able to remove the net income limit through BBCE. Indeed, most other states have done so.[5] But not Hawaiʻi.

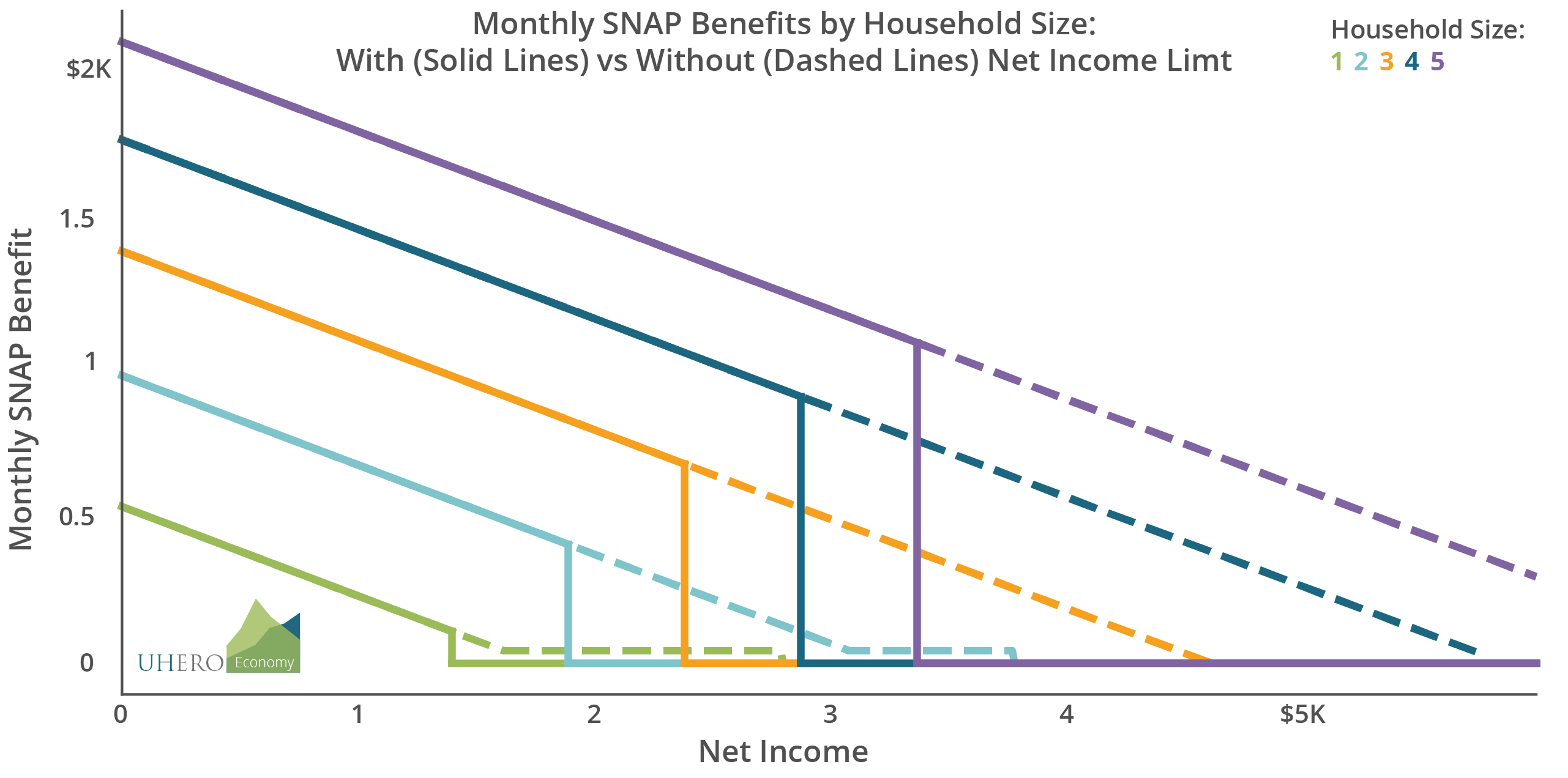

The net income limit can have very large effects. The figure below shows how SNAP benefits in Hawaiʻi vary with net income for households of different sizes. The solid lines depict the status quo (with the net income limit in place). The dashed lines show what would happen if it were removed.[6]

In either case, net income is used to calculate the size of the SNAP benefits a household receives: for households whose income exceeds their deductible expenses, each additional dollar of net income reduces their SNAP benefits by $0.30. However, when the net income limit is in place, there is also a large “benefit cliff”: a level of net income where SNAP benefits suddenly fall to zero when a household receives even one dollar more.

As one of us wrote in a previous UHERO blog, benefit cliffs are not a desirable feature of public policy. They result in large and arbitrary differences in the treatment of households that have nearly identical economic circumstances. They can lead to unpredictable losses of income for households who don’t fully understand program rules. And for households who do understand the program, cliffs strongly disincentivize earning additional income. Low income workers will turn down raises, reduce work hours, and even refuse to accept bonuses in order to prevent themselves from “falling off” a benefit cliff.

The cliff created by the net income limit in Hawaiʻi creates the largest cliff anywhere in the state’s tax and transfer system. In fact, this is one of the largest benefit cliffs anywhere in the United States.[7] For a family of four, “falling off” the cliff will cost them more than $10,000 a year in benefits. This is an enormous amount of money for a household that would be earning, at the very most, $69,000/year in income.[8]

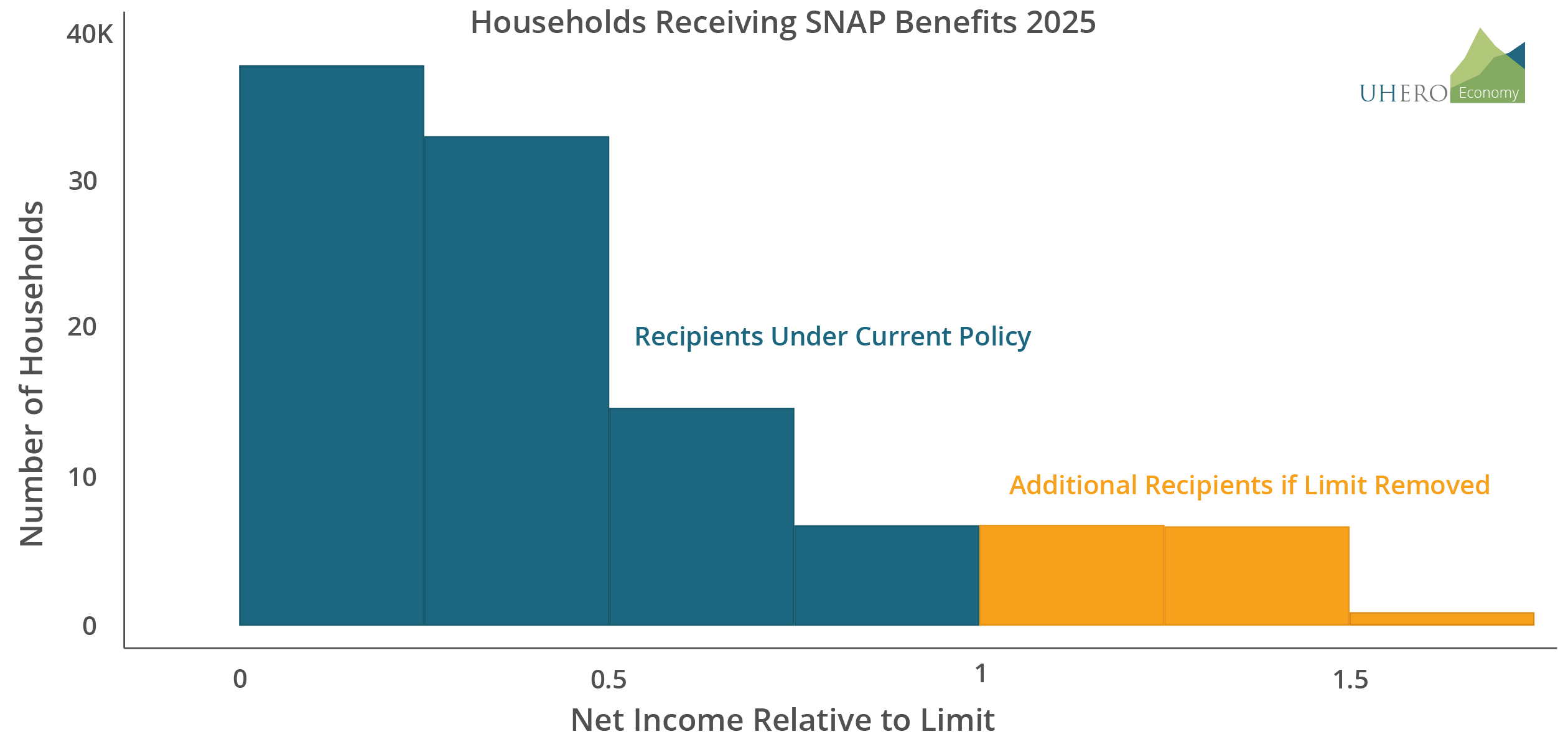

And yet, this cliff need not exist. Hawaiʻi’s Department of Human Services (DHS) can use the BBCE program to eliminate the net income test, and the cliff it creates.[9],[10] 28 states already have BBCE programs that do this.[11] UHERO’s analysis suggests that eliminating the net income test now could ensure that between 13-14,000 additional households will receive benefits in the average month in 2025 (see the figure below). This change would deliver $40-45 million in benefits to these households over the course of that same year.[12],[13]

The long-run benefits of removing the net income limit could be much greater. Many households that are eligible for SNAP benefits do not participate in the program. But removing the net income limit may well increase these participation rates.[14] Recent research shows that SNAP reforms which simplify rules and expand eligibility can increase the share of eligible households participating.[15] In addition, the removal of the net income limit will likely have positive effects on the state’s economy and tax revenues, through both the influx of additional financial resources, and the elimination of a huge work disincentive.[16]

These changes could be made at little cost to the state, which would only need to pay half of the administrative costs associated with the additional SNAP cases that would result. In 2019, the state’s share of Hawaiʻi’s SNAP administrative costs was only about 5.6% of the value of the benefits issued to Hawaiʻi households that year. If this figure also reflects the costs of additional SNAP beneficiaries, that suggests a return to the state of nearly $18 in benefits for every $1 spent on administrative costs.[17]

It is rare in public policy to see a case where such large benefits can be delivered at such a low cost, especially with such an immediate and certain return on investment. The reason, of course, is that these benefits are financed not by the state government, but almost entirely by the federal government.

Given this situation, the state has every reason for the state to remove the net income limit. Arguments against the generosity of welfare benefits often take for granted the perspective of the federal government’s budget, but that perspective has no relevance to the question of what the State of Hawaiʻi ought to do in this case. Concerns about the disincentive effects of expanding SNAP benefits in this way are also misplaced: it is highly unlikely that the additional disincentive effects introduced by expanding the program are as large as those the net income limit currently creates.[18]

UHERO and HIPHI have presented this policy recommendation to DHS. In response, DHS has indicated its intention to pursue the removal of the net income test, paving the way towards a more efficient and equitable SNAP program in Hawaiʻi.

By removing the net income test, Hawaiʻi would provide a huge benefit to families in need with minimal cost to the state. This change would eliminate arbitrary unfairness from the tax/transfer system, and to ensure that those who want to earn more money will gain rather than losing as a result of their efforts. Most policy decisions are hard. This one is not.

1 Based on numbers for Hawaiʻi in the most recently available SNAP data tables.

2 SNAP asset limits are notoriously costly to enforce, and in practice, do not seem to have a large impact on the number of eligible applicants. See, for example, the discussion of asset limits in Lin (2023).

3 https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R42054/48

4 See page 32 of this DHS report.

5 For information about rule variation across states, see the SNAP Screener database. Other sources, such as the Atlanta Federal Reserve’s Policy Rules Database, or to this Mathematica report, are broadly similar but contain some errors. For example, both these sources have miscoded the rules for Hawaiʻi.

6 The figure is not completely accurate in many cases. Even if the net income limit were removed, households would still need to meet the gross income limit to qualify for benefits. Nonetheless, the cliff created by the gross income limit would be much smaller. In my impact estimates—reported later in this post—I account for the effect of the gross income limit.

7 While no comprehensive survey of benefit cliffs sizes exists, the greater generosity of Hawaiʻi’s SNAP benefits relative to most other states means Hawaiʻi’s SNAP benefit cliffs are larger than anywhere outside Alaska. In some other states, certain child care subsidies generate cliffs that can also be quite large, though usually not quite as large as Hawaiʻi’s SNAP benefit cliffs. See this paper for example.

8 This is the gross income limit for a 4 person household: the highest their total income can be to still receive SNAP benefits. The typical income of these is substantially lower, as most households will fall off the cliff created by the net income limit well before their total income reaches the gross income limit.

9 As mentioned in footnote 6, while the “gross income test” will still lead to a SNAP benefit cliff for some households, this cliff would be much smaller than the one the net income limit current creates. Furthermore, there is nothing that the state can do to change this.

10 Eliminating the cliff would not require a legislative change, but rather a change to administrative rules. Specifically, the provision found in §17-663-169(c)(2) of the Hawaiʻi Administrative Rules (pg. 663-85) appears to be responsible for the continued imposition of the net income limit.

11 DC, Guam, and the Virgin Islands also waive the net income test for everyone. A further 6 states waive the net income test for at least some residents.

12 UHERO’s analysis—performed by Dylan Moore—is based on an enriched version of the Policy Engine microsimulation model, which can be used to forecast the impact of tax/benefit policy reforms in Hawai‘i. Using a combination of the SNAP Quality Control data on SNAP recipients in Hawai‘i, and aggregate statistics on SNAP benefits in Hawai‘i (from the USDA), a model of the share of eligible households receiving SNAP benefits (the takeup rate) was estimated. This allows for forecasting the impact of removing the net income limit, assuming that the reform does not change the SNAP takeup rates. As noted below, this assumption is implausible: the policy change will likely increase the takeup rates, but predicting the size of this effect is difficult.

13 Changes to net income limits through BBCE that have happened in the past and in other states have not created such dramatic changes. But Hawaiʻi is different: the maximum SNAP benefit amount is more generous here than in many other states. In practice, this means that in many other states, eliminating the net income test would have little effect on benefits, because most households who fail the net income test have already seen their benefits phased out to near-zero levels. In Hawaiʻi by contrast, benefits are still quite large when net income goes over the limit. In addition, a recent increase to maximum benefit generosity in all states has further increased the size of the net income limit SNAP cliff.

14 UHERO estimates that around 50,000 households each month would be made newly eligible for benefits by removing the net income limit, but that only 13-14,000 of them will participate. These numbers are based on the conservative assumption that the reform will not impact takeup rates (the share of eligible households participating), and that takeup rates of newly eligible households will be broadly similar to those of currently eligible households near the net income limit: around 25-30% in UHERO’s model. If removing the net income limit caused this rate to rise to around 40-50%, the impact of removing the net income limit on the number of households receiving SNAP benefits could be double the figure above. This is not wholly implausible, as UHERO estimates an 80% takeup rate at slightly lower levels of net income. However, the size of the takeup rate effect is extremely uncertain.

15 For example, see Gray (2019), who explores incomplete SNAP takeup in Michigan, as well as the effects of a simplification of reporting requirements for beneficiaries. Lin (2023) looks at the effects of the introduction of BBCE in many states. In both cases, the results suggest that some eligible households do not claim SNAP benefits, and that the adoption of simpler rules can increase participation rates. These results are broadly consistent with a larger literature about determinants of program participation. See Ko & Moffit (2024) for a recent review.

16 If the elimination of the cliff leads households to increase their incomes, this will of course increase income tax revenue and GET revenue in many cases. The SNAP benefit payments themselves will likely decrease GET revenue in the short run because while households who receive additional benefits may spend more in total, spending paid for with SNAP benefits is not subject to the GET. In the medium to long term, additional spending in the economy may lead to some multiplier effects which enhance economic activity and tax revenue (through both the GET and income taxes).

17 This figure is based on information reported in the most recently released SNAP data tables. It could be either an under- or overestimate. Some portion of administrative costs are fixed costs of running the program, regardless of how many beneficiaries there are, so costs may be less than 5.6%. On the other hand, the new beneficiaries would receive somewhat smaller benefit amounts/household than the current beneficiaries, so the cost per dollar of benefit may be higher than it is with the current beneficiaries. Note, even if costs are double this figure, that would still represent a remarkably cheap opportunity to obtain federal funds.

18 Even someone who objects to expanding total welfare benefits in the state should not oppose eliminating the net income test. Rather, such a person should endorse pursuing this change, accepting the federal money, and simultaneously decreasing state spending on state-funded benefits/tax credits targeted to the same population.