BLOG POSTS ARE PRELIMINARY MATERIALS CIRCULATED TO STIMULATE DISCUSSION AND CRITICAL COMMENT. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED ARE THOSE OF THE INDIVIDUAL AUTHORS. WHILE BLOG POSTS BENEFIT FROM ACTIVE UHERO DISCUSSION, THEY HAVE NOT UNDERGONE FORMAL ACADEMIC PEER REVIEW.

By Steven Bond-Smith

The following is adapted from a presentation I recently gave at the Western Regional Science Association meetings on the Big Island.

My research focuses on the implications of theoretical regional economic models for small and isolated places, like Hawaii. These are places where distance matters such that they are generally unable to access large local markets or other local sources of external scale economies. The term “external scale economies” refers to the productivity benefits of close proximity to large-scale economic activity. Because of the interaction between distance, scale, external economies, and the mobility of people and economic activity, small economies in isolated places have very different characteristics and require unique policies for economic development.

Short-term shocks and long-term declining productivity growth

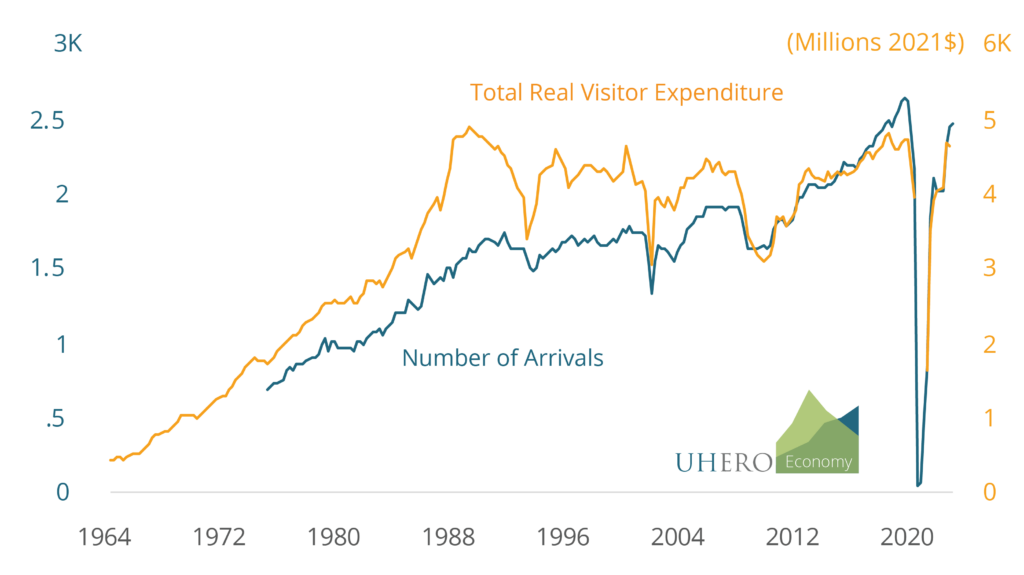

It’s not just the pandemic. While COVID-19 is the biggest shock to tourism yet, the industry is periodically punctured by shocks: the 1991 recession, 9/11, the 2001 recession, and the Great Recession, all lead to sharp declines in tourist numbers and spending.

Figure1: Quarterly tourism data Hawaii, 1964-2022

Notes: Real visitor spending adjusted for Urban Hawaii CPI.

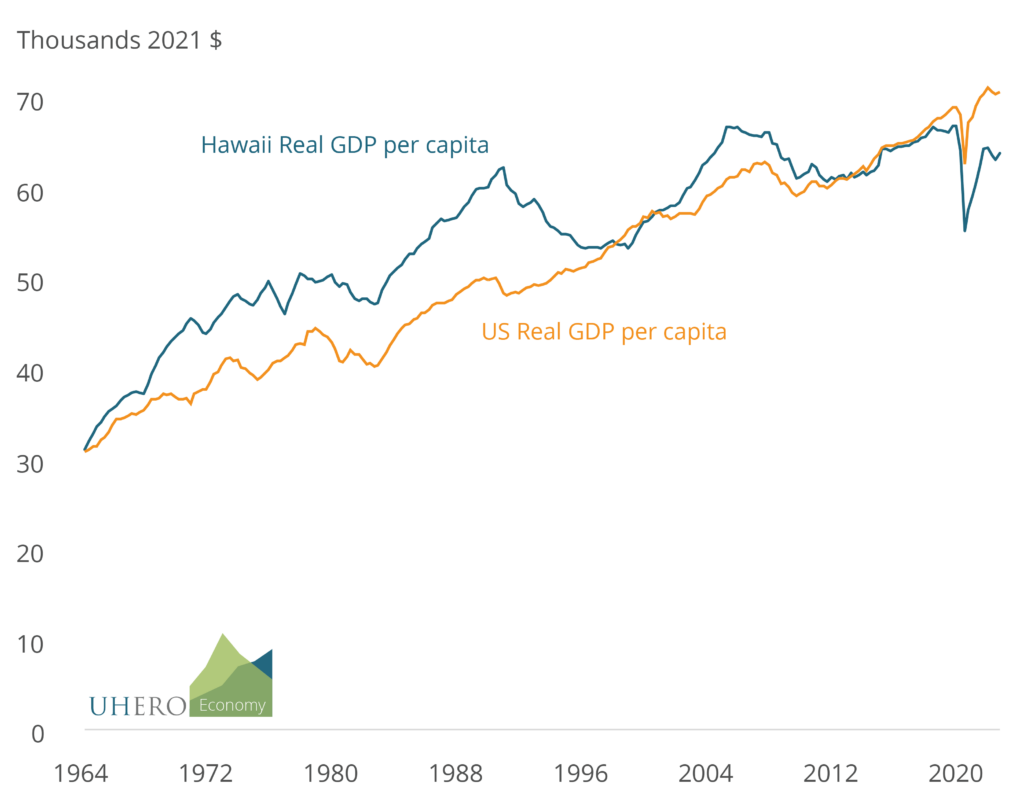

It wasn’t always this way. For a long time, tourism in Hawaii experienced significant growth in both visitor numbers and expenditures. Technologies such as the jet engine, and a growing and increasingly wealthy middle class who wanted to vacation in Hawaii, made tourism a lucrative industry. This translated into substantially higher Real GDP per capita in Hawaii than in the rest of the United States.

But in recent decades visitor spending stopped growing while the number of tourists continued to increase. And for several decades now, the tourism industry has not contributed to growth in per capita GDP in the same way that it had in the past.

As a result, Hawaii has fallen dramatically behind the rest of the US in terms of per person income growth. The long run growth in Hawaii’s real GDP per capita has fallen from 1.9% prior to 1990 to 0.5% during the last three decades. US real GDP per capita annual growth has also fallen, but by much less, from 1.5%, to 1.1%. This means Hawaii went from a real per capita trend growth rate 0.5 percentage points higher than the US to 0.6 percentage points lower.

Figure 2: Quarterly real GDP per capita, Hawaii, 1964-2021

Notes: Quarterly GDP per capita adjusted by Urban Hawaii CPI to 2021 dollars

After three decades of lagging growth Real GDP per capita in Hawaii has now fallen below the US. The COVID-19 pandemic has just exacerbated this long run trend in which Hawaii’s real GDP per capita has now fallen to 10% behind the US overall. If we were to account for regional price differences, Hawaii would be even further behind.

Why so specialized?

Tourism represents 17% of Hawaii’s economy, but less than 2% of the national economy. Tourism’s share of exports from Hawaii is even more extreme. The specialization and dependence on tourism means that Hawaii is hit hard by those shocks that hurt visitor numbers because there are no other sectors to expand when tourism contracts. But why is Hawaii’s economy specialized at all? Why hasn’t it developed a more diversified economic base? And what can we do about it?

Comparative advantage

Many economists would argue that a tropical climate is Hawaii’s comparative advantage and trying to diversify will only make us poorer. While that’s partly true, if it were simply a story of comparative advantage, a new comparative advantage would emerge as the historical comparative advantage has faded. That hasn’t happened. There is a lot more to the story which makes it an incredibly difficult problem to solve.

Isolation, scale and economic integration

I argue that the cause is a combination of isolation, small scale, and economic integration.

The external scale of the economy affects productivity. Examples of these external scales include things like the size of the local labor market, the range of available skills, the number of potential suppliers, and the extent of local R&D. These external economies increase productivity in particular tasks and attract the specific economic activities that benefit from these advantages

Because of their small scale, small economies are often unable to access the productivity benefits of external scale economies. And in isolated places, it is also difficult to access the external scales of nearby states, the wider national economy, and the global economy. As a result, small, open, and isolated places will tend to become much more specialized because it creates the only type of local external scale that they can create—the scale of their industry specialization—in order to access these productivity advantages.

This specialization makes these places better off in the medium term. The initial expansion of the tourism industry generated substantial growth in Hawaii leading to GDP per capita 40% higher than the mainland by the late 1980s. The same story describes Western Australia’s specialization in iron ore, New Zealand’s specialization in food and agriculture, and Alaska’s specialization in Oil & Gas. Small, isolated economies are able to specialize, because economic integration allows these places to trade for the things that they’re not specialized in. The specialization is partly determined by comparative advantage, such as a resource endowment like Hawaii’s climate and host culture, but small open economies specialize in order to access a form of scale economies, not only to benefit from a comparative advantage.

The economic development problem

This tendency presents a long-term economic development problem. An entrepreneur won’t be particularly productive if they start a business in a new industry that isn’t already established. Even if there are many entrepreneurs who want to start businesses in this new industry, they’re each waiting for another to go first. This is a coordination problem facing economic development in small, open and isolated places that mostly goes unnoticed by mainstream economics because it doesn’t occur in larger, diversified or more connected places. Isolated places cannot use the external scale of the national or global economy as a stepping stone.

This explanation describes both the period of growth that benefited from Hawaii’s specialization in the tourism economy, and its more recent stagnation in which no new industry has emerged to provide a significant alternative source of growth. It also explains Hawaii’s past specialization in plantation agriculture and a similar growth pattern before Hawaii became a tourist paradise.

Diversifying into new industries and establishing them at scale

So, based on this argument, I expect that small and isolated economies face a periodic coordination problem for economic development as productivity growth in their specialization eventually deteriorates. To escape this trap requires either a government, or a large investor to undertake an initiative that makes a strong commitment to establish a new activity, or range of activities, at scale. Which is exactly what Hawaii did when the State invested in airports and other infrastructure in the 1970s in a bid to expand tourism and diversify away from plantation agriculture.

Tourism isn’t going away, but establishing another industry at sufficient scale to benefit from external scale would provide resilience to periodic shocks, and provide new opportunities for productivity growth. But what should Hawaii do? When Hawaii’s government chose to emphasize tourism, the opportunity probably seemed relatively obvious, but how do we find other opportunities today?

Diversify into what?

My ongoing research agenda aims to reveal clues from our existing economy about what industries offer potential opportunities for economic development. This is based on a few stylized facts from recent research. Firstly, economies grow by diversifying into related industries. Two industries are related if they both use the similar capabilities, such as a shared pool of workers with particular skills. For example, Hawaii’s expertise in caring for visitors could transfer to health support and rehabilitation in the healthcare industry, which would have very different demand dynamics than the tourism industry. I am currently working on a project to identify related industries based on the common location of employment in pairs of industries across the US. If pairs of industries frequently locate together, it means they probably share all of the same underlying conditions they require to be successful.

Secondly, if some of those conditions are uniquely tied to Hawaii, then those industries cannot easily shift somewhere else: they have to locate in Hawaii. We need to emphasize industries that require Hawaii’s specific characteristics, especially if these industries also bring other capabilities to Hawaii that wouldn’t otherwise choose to be here. For example, Hawaii is located on the trans-Pacific internet cables that make it a potential location for data centers to host international web-based services that would act as a stepping stone for U.S. start-ups to expand internationally. In this way, Hawaii becomes a gateway to Asia for bits and bytes. Similarly, Hawaii could be the ideal stopover location for transit between Asia and South America, specifically targeting business travel. China and Brazil are two of the fastest growing economies in the world. And astronomy relies on Hawaii’s high mountains and clear air, which brings a unique STEM industry that is otherwise difficult to come by.

And thirdly, because of external scale economies, industries will tend to sort into locations with different scales. Hawaii’s economy is small, so we need to find industries that suit small economies. Finance is much more suited to very large cities like London, New York, and San Francisco, but professional, scientific, and technical services are much more common in metro areas of around 1 million people like Honolulu. Similarly, food manufacturing is common in much smaller cities with surrounding agriculture such as around Hilo.

I cannot tell you exactly what Hawaii should diversify into. No one person has these answers. No government or policy-maker has those answers. The answers are in the community. They are the people with deep knowledge of the factors holding back new ideas. But that’s generally the framework I am using to short-list industries with potential: (i) related industries that (ii) make use of uniquely Hawaii capabilities and (iii) are appropriate for our small scale. All of this research agenda aims to identify which industries we should expect to see in Hawaii and each of its counties, but are currently missing or weak. Then policy-makers and entrepreneurs can take a closer look at those industries to see what is preventing them from being stronger. Initiatives need to be designed with a commitment by governments and community organizations to address these barriers. This commitment helps to overcome issues with external scale economies so that initiatives reveal the true opportunities by discovering them in the marketplace in order to benefit the communities that take up those opportunities.

UHERO Focus: UHERO’s Steven Bond-Smith on Hawaii’s tourism centered economy and its prospects on diversifying into other industries.

Click here to view the working paper.

Publication: Bond-Smith, S. (2023). Diversifying Hawai‘i’s Specialized Economy: A Spatial Economic Perspective. Economic Development Quarterly, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/08912424231183941