BLOG POSTS ARE PRELIMINARY MATERIALS CIRCULATED TO STIMULATE DISCUSSION AND CRITICAL COMMENT. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED ARE THOSE OF THE INDIVIDUAL AUTHORS. WHILE BLOG POSTS BENEFIT FROM ACTIVE UHERO DISCUSSION, THEY HAVE NOT UNDERGONE FORMAL ACADEMIC PEER REVIEW.

By Byron Gangnes

The Federal Reserve has raised interest rates sharply over the past fifteen months, and Fed officials have signaled that perhaps two more quarter point hikes are coming. How high are interest rates compared with past Fed tightening episodes? Are they high considering the state of the US economy?

First, a little about interest rates. (You can skip this if you are econ savvy.) The interest rate you pay or earn is called a nominal interest rate, that is, an interest rate measured in plain old dollars. Interest rates that are relevant for decision making are real interest rates: interest rates adjusted for inflation. To see why this is so, consider the following example:

I am deciding whether to make a one-year loan to my daughter at an interest rate of 5%. Ignoring the (almost certain?) risk that she will fail to repay me, whether 5% is a good deal depends in part on what I think inflation will be over the coming year. Suppose I think that inflation will be 2%, then a one-year loan will net me a 3% real rate of return after adjusting for inflation—not the full 5%, because the purchasing power of the repaid dollars will be less than when I made the loan. But if inflation turns out to be 6%, then I will have lost money on the deal, since I will get repaid (it could happen) less purchasing power than I gave her up front. Of course it’s tricky, because when I consider making the loan, I have to form an expectation of what inflation will be, and that could turn out to be wrong.

So expected real interest rates are what decision makers should care about. This is true for my loan to my daughter, and for any other lending, borrowing, or investing decision. And to evaluate whether prevailing interest rates are high or low, we need to consider not just nominal, but also real interest rates.

OK, back to the Fed.

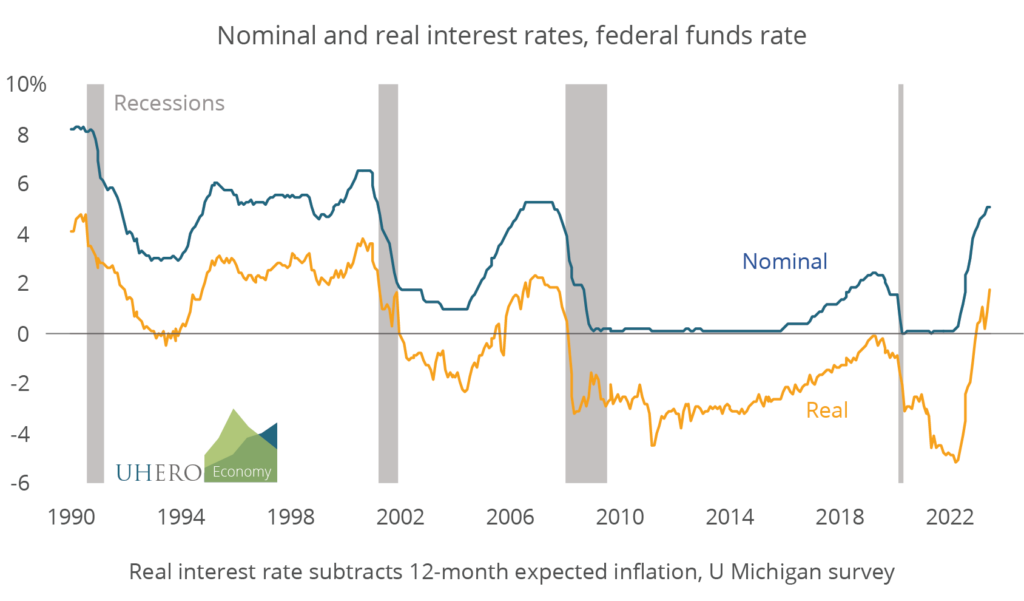

The Federal Open Market Committee has raised its policy interest rate, known as the federal funds rate, 10 times since the beginning of last year. The fed funds rate is important because interest rates on many loans and bonds are directly or indirectly linked to this interest rate. (Long-term rates like mortgages are less closely linked.) The Fed is currently maintaining the fed funds rate within a range of 5% to 5.25%. Here is a graph of the fed funds rate going back to 1990:

A few things to note:

- The Fed has moved the nominal federal funds interest rate up and down over time as it has sought to moderate the ups and down of the US business cycle. They have cut rates when they wanted to provide economic support during recessions and their aftermath, and they have raised interest rates late in expansions when they wanted to discourage spending and prevent the economy from growing unsustainably fast.

- Often (but not always), real interest rates have gone negative during periods of Fed interest rate cuts. Note that they were particularly low in the period following the 2000s housing boom/bust, and they were exceptionally low during the COVID-19 pandemic and early recovery period.

- The Fed does not directly control the real interest rate, since this depends importantly on what people expect inflation to be. When the Fed held nominal rates near zero during much of the stagnant 2010s and during the recent pandemic, real rates were negative because of expected inflation. The recent period saw such exceptionally low real rates because inflation and inflationary expectations soared during the pandemic and its aftermath.

Substantially negative real interest rates are just what you want if you are trying to stimulate a very weak economy—they make it cheap for consumers to borrow to buy cars, and for businesses to invest in new factories, for example. But if the economy is in danger of overheating, that is, growing unsustainably fast and driving inflation, the Fed needs to raise interest rates enough to get real rates out of that super-stimulative negative rate territory.

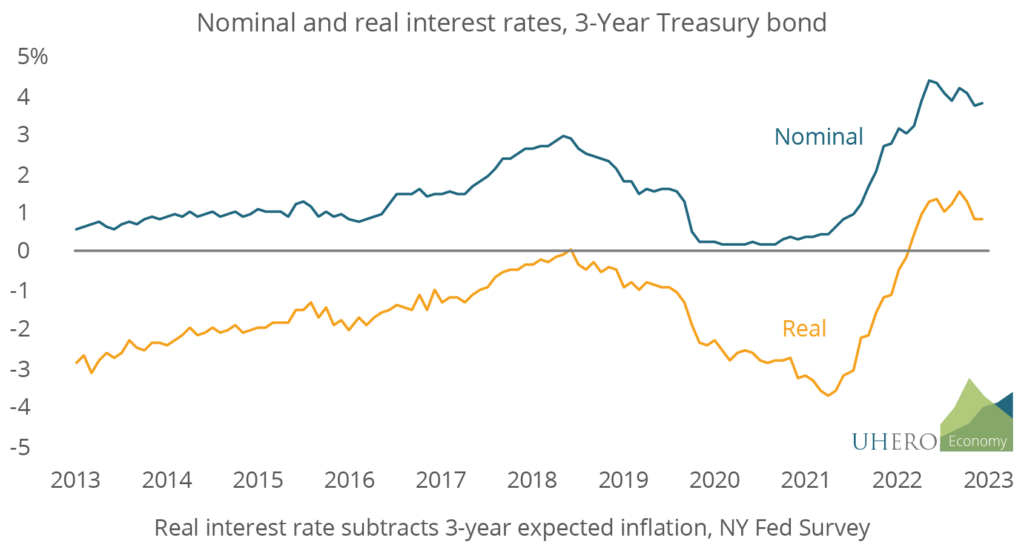

I mentioned that changes by the Fed in the fed funds rate also affect market interest rates, especially other relatively short-term rates. We can see that here in the path of nominal and real interest rates for three-year US Treasury bonds. Real rates on these bonds also fell precipitously during the pandemic and its aftermath, and they have risen since the beginning of 2022.

Notice that for both the fed funds and the three-year T-bond, because of persistently high expected inflation real interest rates remained negative well into this tightening cycle. Only now with rates above 4-5% and inflation cooling (albeit slowly) has the fed funds rate turned positive.

How high are current real rates compared to past tightening episodes? As you can see from the first graph, the real fed funds interest rate is now about 2% based on consumers’ expectations of inflation over the next twelve months. That’s roughly on par with many past rate hike periods.

Whether that’s high enough to meet the Fed’s goals depends on the current economic environment. If you look at labor market indicators, conditions are not excessively tight by some measures (for example, the unemployment rate is similar to its level at the end of the Fed’s last contractionary cycle), but job and wage growth are more buoyant. The big difference is that inflation, while trending lower, remains well above the Fed’s long-run goal of 2%. So it is understandable that rates may go a bit higher and remain high longer than in many past tightening cycles.

It is impossible to know whether rates have now gone high enough, simply because interest rate hikes to date will take a while longer to feed through fully to lower demand and lower inflationary pressure. And the recent period, with its pandemic-related supply-side constraints, differs from other expansionary periods. But we do know that real rates will rise further in coming months even without additional Fed nominal interest rate hikes. That’s because inflation expectations will ease further as experienced inflation continues to trend downward. The Fed may well have already done enough to cool the economy.