BLOG POSTS ARE PRELIMINARY MATERIALS CIRCULATED TO STIMULATE DISCUSSION AND CRITICAL COMMENT. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED ARE THOSE OF THE INDIVIDUAL AUTHORS. WHILE BLOG POSTS BENEFIT FROM ACTIVE UHERO DISCUSSION, THEY HAVE NOT UNDERGONE FORMAL ACADEMIC PEER REVIEW.

By Byron Gangnes

Try to tell people that we are not in a recession, and you will get a lot of pushback. After all, jobs are harder to come by, prices are high, and some people are struggling to finance credit card debt. Some households are feeling these effects, and those who are not may be more pessimistic now than in past months.

But a recession is a very particular thing. The economy must actually be contracting, not just slowing.

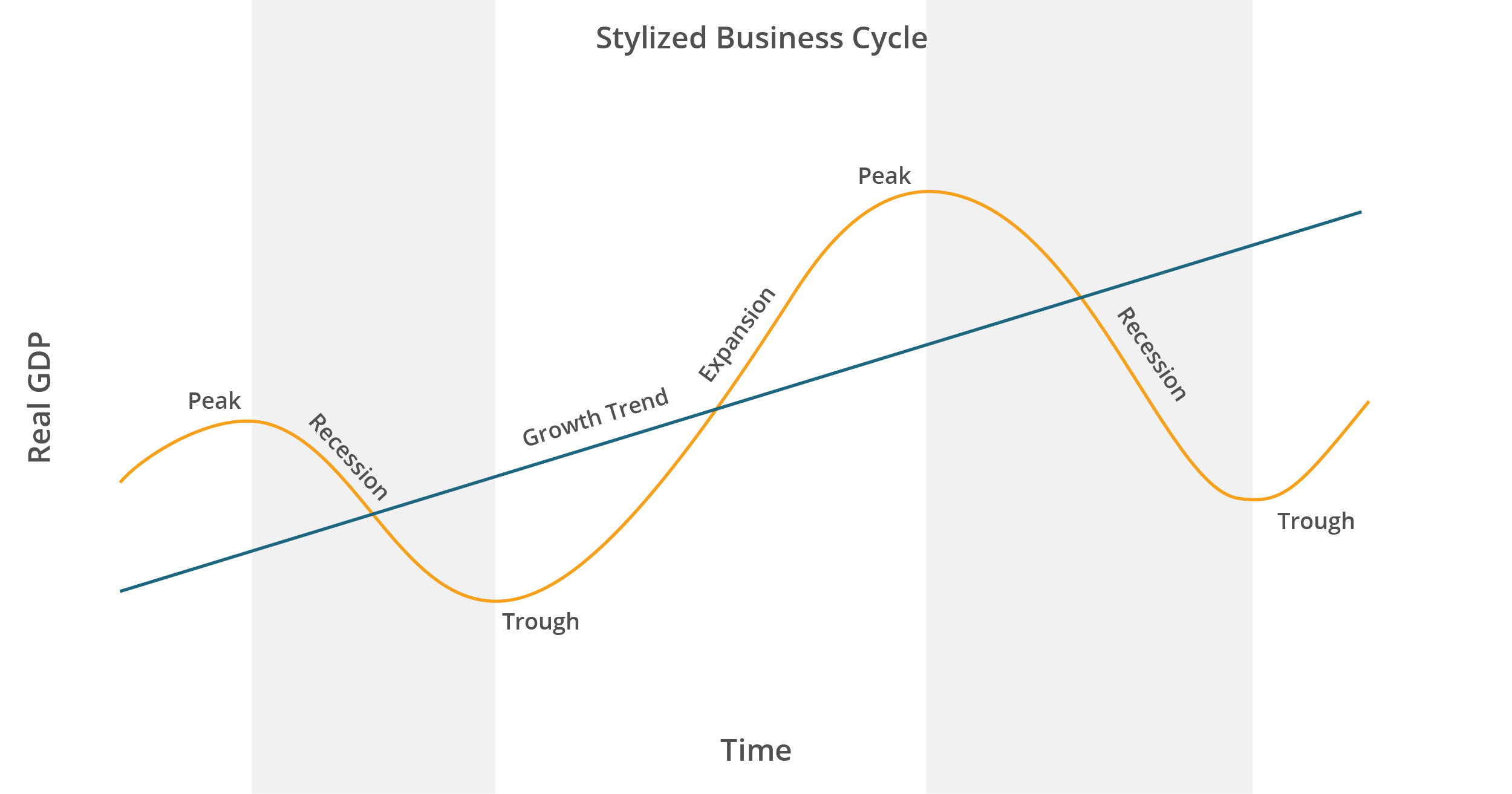

Here’s a stylized view of the business cycle à la Econ 101. An economic expansion ends when a slowing economy begins to contract. The high point before a recession begins is the business cycle peak. A recession bottoms out at the trough before the next expansion begins. Expansions typically last much longer than recessions.

To know whether we have entered a recession we need to know whether the expansion has peaked, and the economy has begun to contract. But to qualify as a recession the economy must have made a significant and sustained downturn, because we don’t want to call any short, small downward wiggle in the economy a recession. How do we decide when that has happened?

A common simple definition of a recession is:

- two consecutive quarters of negative real GDP growth.

The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER)’s Business Cycle Dating Committee, the semi-official arbiter of US business cycle turning points, has a more sophisticated definition. A recession,

- “…involves a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and lasts more than a few months.”

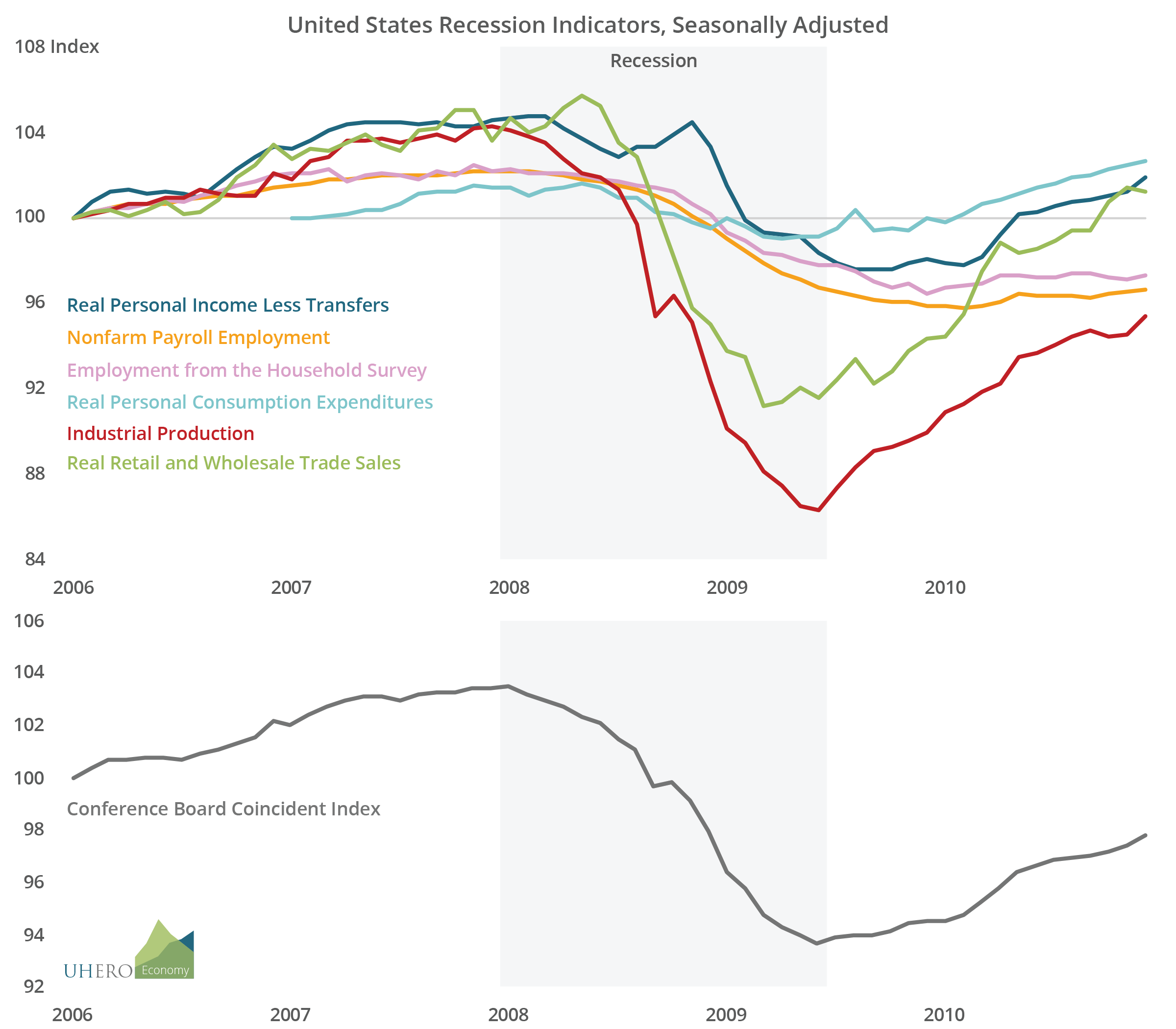

Since both definitions require a sustained downturn, a recession is not called until well after it has begun. The NBER Committee looks at a range of monthly indicators of inflation-adjusted (real) economic activity to assess this, including. “…real personal income less transfers, nonfarm payroll employment, employment as measured by the household survey, real personal consumption expenditures, wholesale-retail sales adjusted for price changes, and industrial production.”

They then make a judgement about whether these factors as a group demonstrate a decline in activity of sufficient “depth, diffusion, and duration” to confirm that a recession is underway.

The Conference Board publishes an average of four of these indicators, termed a “Coincident Economic Index”, since it is intended to show the position of the economy at the current time. (The four indicators they include are payroll employment, personal income less transfers, manufacturing and trade sales, and industrial production.)

The 2008-2009 Great Recession

We can see most easily how these data typically move over a business cycle by looking at the deep 2008-2009 “Great” recession. Here I have normalized the series so that they all have a starting value of 100 in January 2006. (Data on real personal consumption expenditures does not begin until 2007.)

The NBER judged that the 2000s business cycle peaked in December 2007, with a recession beginning in January 2008. The trough of the recession occurred in June 2009, with the next expansion beginning the following month. The peak of that expansion in 2019 is beyond the time frame of this graph.

Not all measures of economic activity reach their peak or trough at the same time. So, there is a need for judgement in deciding when the turning points occur. The NBER has tended to give more weight to some of these indicators than to others: “There is no fixed rule about what measures contribute information to the process or how they are weighted in our decisions. In recent decades, the two measures we have put the most weight on are real personal income less transfers and nonfarm payroll employment.”

The Coincident Economic Index, which, as we saw, combines four indicators, matches the turning points well.

Where is the US economy today?

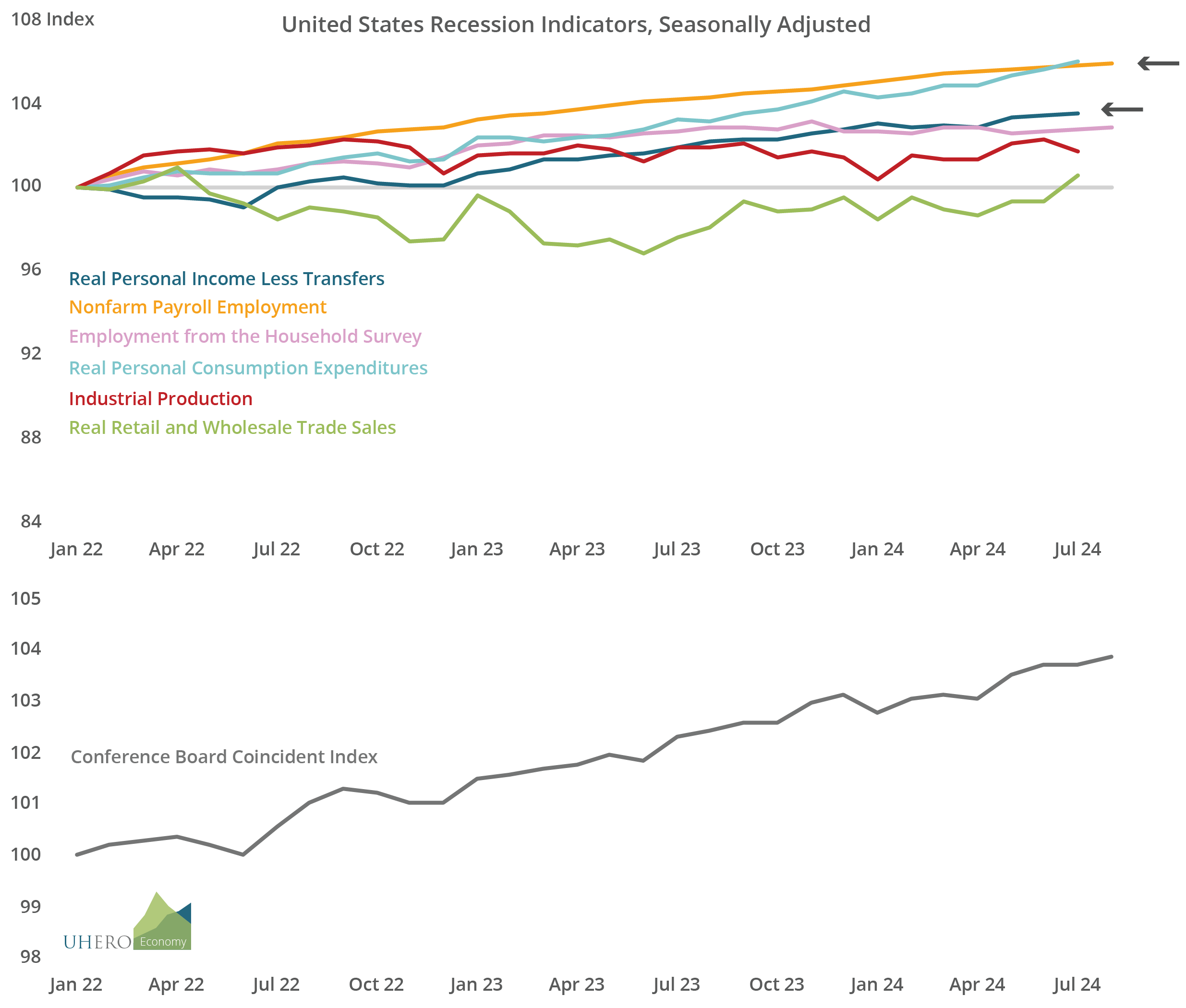

Here is a comparable set of charts for the US as of July-August 2024. (I have highlighted with an arrow the two indicators that the NBER says they give the most weight to.) We can see that there has been quite a variety across the six indicators over the past three years. Neither the early 2022 drop in real income or the longer decline in retail sales qualified as a recession, because the downturn was not widespread—payroll jobs continued to rise steadily, and consumer spending too, with a few brief dips.

Recently, five of the six indicators have been rising, including the two most closely watched by the NBER committee, indicated by the two arrows. Industrial production has been fluctuating, and employment from the household survey has been flat. The Coincident Economic Index has not shown any sign of a sustained decline.

It can be hard to see in this graph of the normalized levels of each series whether the measures are expanding or contracting if they are changing by small amounts. The following graph shows recent monthly percentage changes in the indicators.

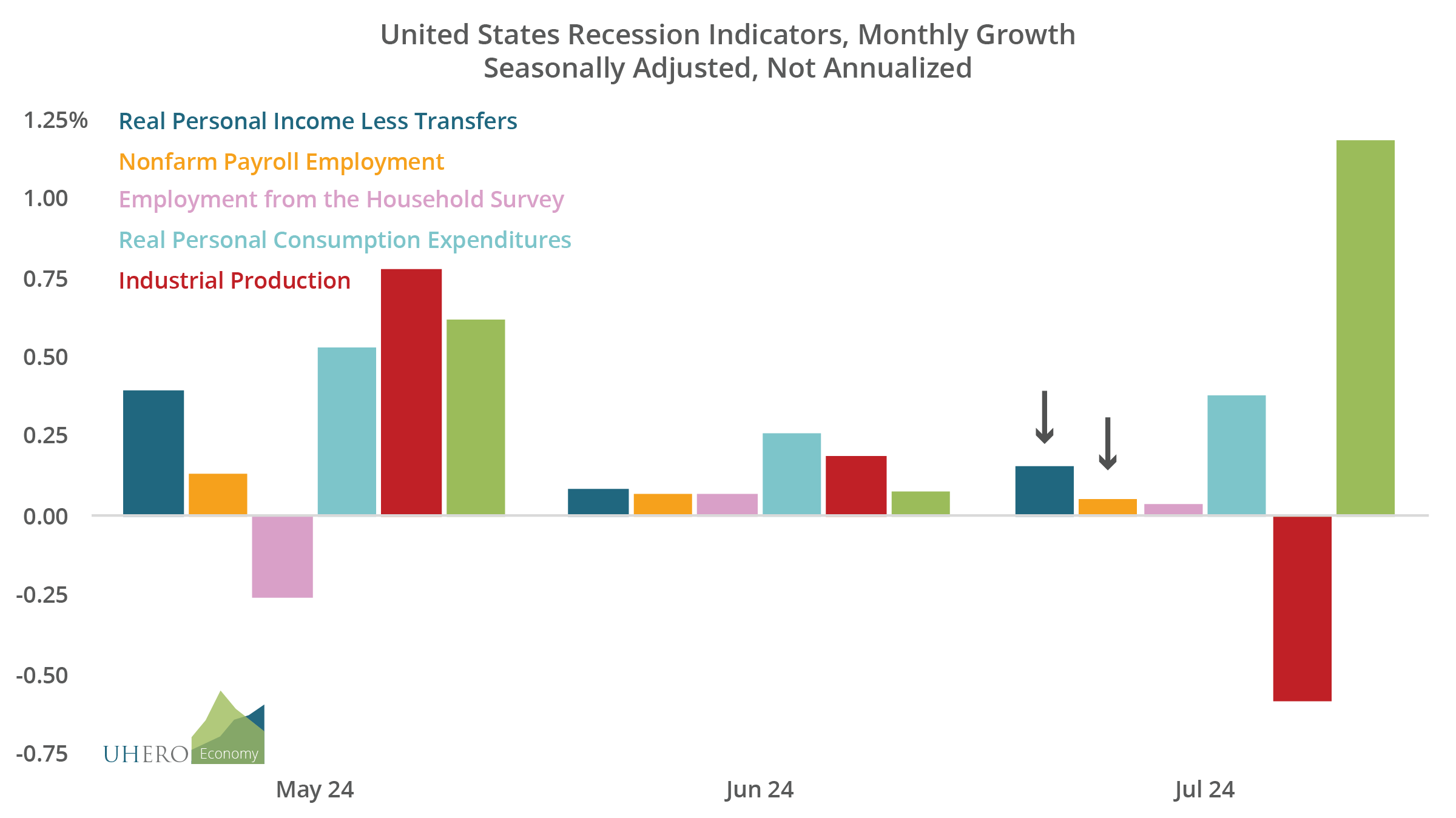

As you can see, most indicators have expanded in recent months, with a couple of exceptions. And all indicators but industrial production rose in July. The two indicators that are given the most weight by the NBER rose in all three months. Except for buoyant consumer spending, the July increases were modest, as the rate of growth of the economy has slowed. The Coincident Index (not shown) dipped in July, but rose again in August.

We won’t know for a while if we enter a recession

One problem with the NBER Committee’s approach is that business cycle dating is retrospective. The NBER is appropriately cautious in proclaiming start and end dates to expansions and recessions, since there are many monthly ups and downs in the data. So, “…the committee tends to wait to identify a peak until a number of months after it has actually occurred.” If a recession happens, we will not know it immediately, even if we begin to see signs that we may be entering a recession before it is officially announced. Those signs have yet to emerge.

Is there any chance that we could be in recession even if these data do not currently show it? Perhaps, if later data revisions indicate contraction in key indicators. We saw recently a very large downward revision is in store for nonfarm payroll jobs. If that turns out to be concentrated in the most recent months, it could show that the job count has begun to contract. Still, you would need to see a decline in more than just that one indicator before you would say the economy is in recession.

No recession does not mean no pain

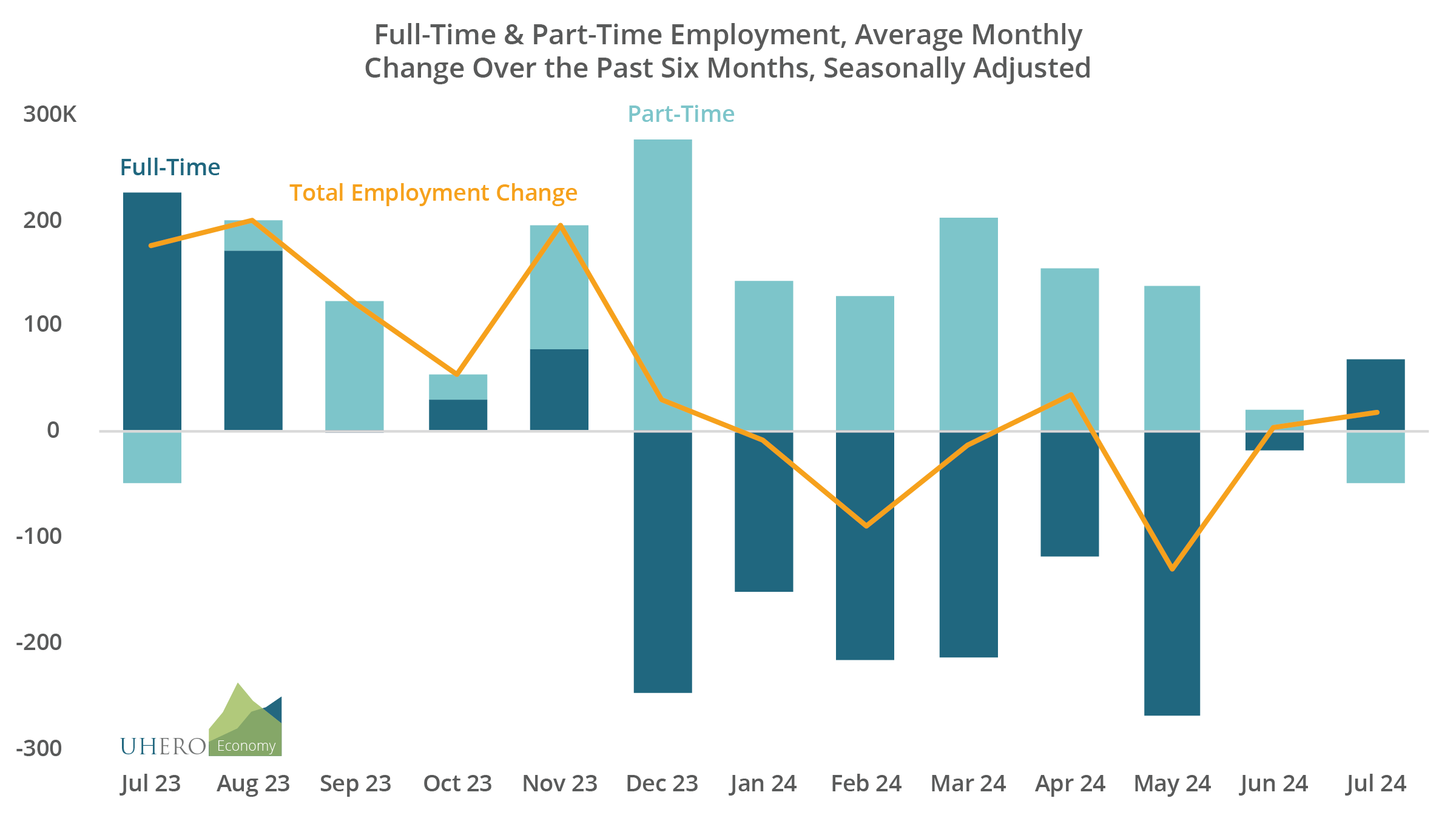

The fact that we are not in recession does not mean that all is well in the US economy. As the discussion above suggests, there are commonly tracked elements that are now essentially flat, notably industrial production, but also employment growth that falls far short of the growth in the payroll jobs reported by firms. Retail sales have been soft but rose recently. And some important measures of economic health not directly related to signaling a recession have deteriorated. For example, the unemployment rate has risen to 4.2% from a low of 3.4% in April 2023, and until the past six months, the fraction of people reporting full-time work has been falling. While the inflation rate has receded, many prices remain substantially higher than they were prior to the pandemic. And, despite moderate overall borrowing levels, the rise in delinquency rates on credit card and auto loans suggests increasing financial stress for some households.

And of course, these macro indicators will not capture differences in economic experience across individuals and families. Depending on the industry they work in, what mix of products they consume, their geographical location, whether they own or rent, and other personal factors, some people are worse off and some better off than suggested by these macro data.

Is this an important distinction? Whether the economy is growing slowly or contracting? In part, it is academic, in the sense that economists who study the causes and consequences of recessions need historical data about when and for how long they occurred, how deep they were, and so forth. But a recession also tends to spin off a host of unique problems, including a sharp falloff in demand for many companies’ products, widespread resulting layoffs, and falling consumer income.

We can say that the economy is underperforming, but that is not the same as saying it is contracting. So don’t call it a recession—at least not yet.