BLOG POSTS ARE PRELIMINARY MATERIALS CIRCULATED TO STIMULATE DISCUSSION AND CRITICAL COMMENT. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED ARE THOSE OF THE INDIVIDUAL AUTHORS. WHILE BLOG POSTS BENEFIT FROM ACTIVE UHERO DISCUSSION, THEY HAVE NOT UNDERGONE FORMAL ACADEMIC PEER REVIEW.

By Maja Schjervheim, Paul Bernstein, Sumner La Croix, Makena Coffman, and Sherilyn Hayashida

For the third year in a row, a carbon tax bill fizzled out at the Hawaiʻi State Legislature. Perhaps it was the difficult timing of introducing a new tax in the wake of a pandemic. Perhaps it was due to qualms regarding the effectiveness, equity, or overall economic impact of such a tax. Economists have long praised carbon pricing as an effective and potentially equitable way to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions at the federal level. But is a carbon tax a viable option for a small island economy like Hawaiʻi?

There is widespread support for GHG mitigation in Hawaiʻi, evidenced by multiple state goals to reduce emissions and, most recently, legislation to become carbon “net negative” before 2045 (HRS §225P-5). These are critically important, science-based goals. But let’s be real. Ambition itself will not solve the climate crisis. Though the cost of renewable energy has fallen dramatically over the last decade, adoption of low carbon technologies and behaviors remains limited because the market prices for fossil fuels do not reflect their true societal cost. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) projects that the mean net present value of the costs of global damages from warming of 2°C is up to $70 trillion in 2100 (IPCC, 2018). Damage costs include, for example, impacts due to sea level rise, major shifts in agricultural productivity and crop loss, as well as losses related to non-market impacts. If fossil fuel prices reflected the true cost of the fuel’s carbon emissions, renewable energy resources and low carbon transportation options would become much more viable and attractive.

Levying a carbon tax set at the “social cost of carbon” (SCC) aims to do just that by adding the cost of damages associated with releasing one additional metric ton of CO2 into the atmosphere. The Obama Administration convened a multi-agency working group to determine the SCC using global economic and climate models. The group adopted a SCC of $56/MTCO2 Eq. in 2025 and $79/MTCO2 Eq. in 2045 ($2020), with a 3% discount rate. The Biden administration has adopted these estimates as a starting point and also announced it will update them to better incorporate the range of climate damages and uncertainty factors, both of which are expected to significantly raise the SCC (Interagency Working Group on Social Cost of Greenhouse Gases, 2021).

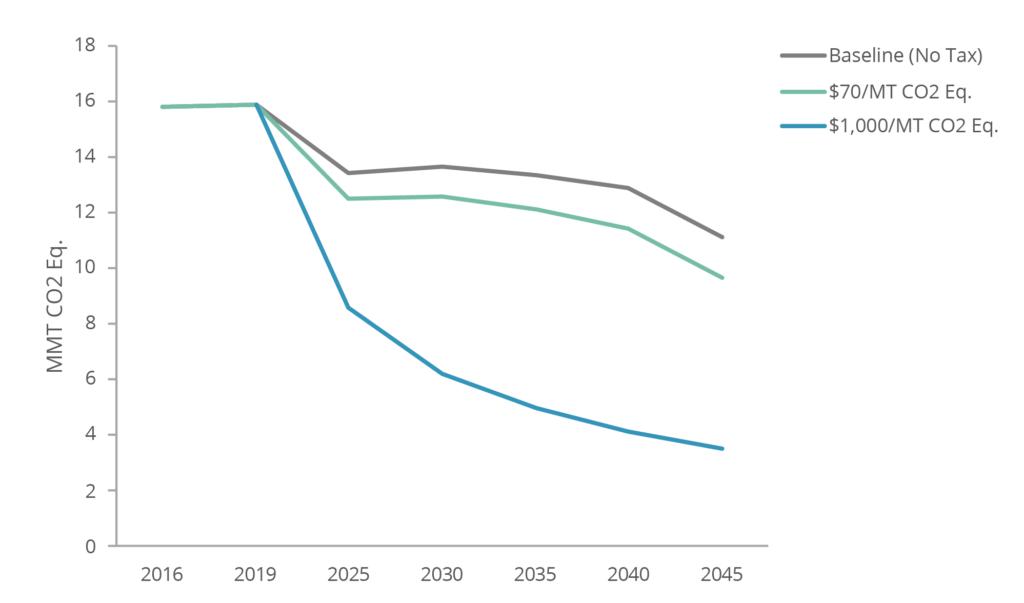

In 2019 the Hawaiʻi State Legislature requested a study to evaluate the economic and environmental implications of a state-level carbon tax in Hawaiʻi and its potential to contribute to the State’s goal of net negative carbon emissions by 2045 (Act 122, 2019). Our team’s report comes to findings that are both encouraging and sobering. As shown in figure 1, a carbon tax set at the level of the federal SCC (“$70/MT CO2 Eq.”) has the potential to reduce statewide emissions by an additional 13% compared to the baseline in 2045. It would take a much higher carbon tax to get near the goal of net negative emissions. A tax that reaches $1,000/MTCO2 Eq. in 2045 reduces emissions by 70% in comparison to the baseline. Emissions reductions come mainly from electricity and transportation sectors.

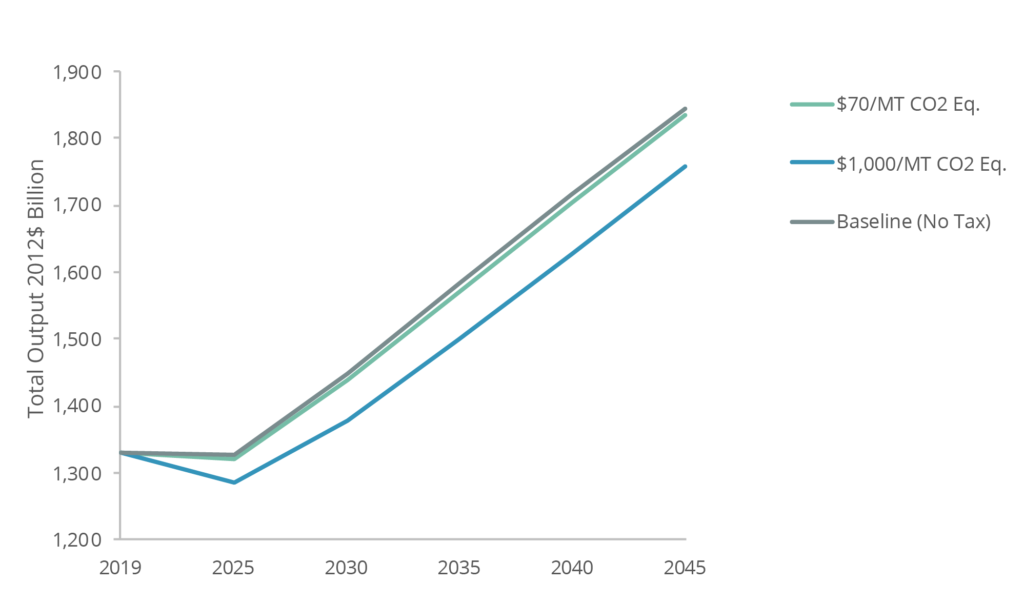

In general, taxes tend to be a drag on economic activity and the carbon tax is no exception. A carbon tax set at the SCC has a relatively small impact to Hawai‘i’s overall economy while the much higher price pathway comes at much higher cost, as shown in Figure 2. Whereas there is a 0.5% reduction in economic output in 2045 under the SCC-level carbon tax, the higher price would reduce economic output by about 5%. To put that in context, this means that by 2045 the output of the Hawai‘i economy will have grown by 32% from 2025 rather than 39%.

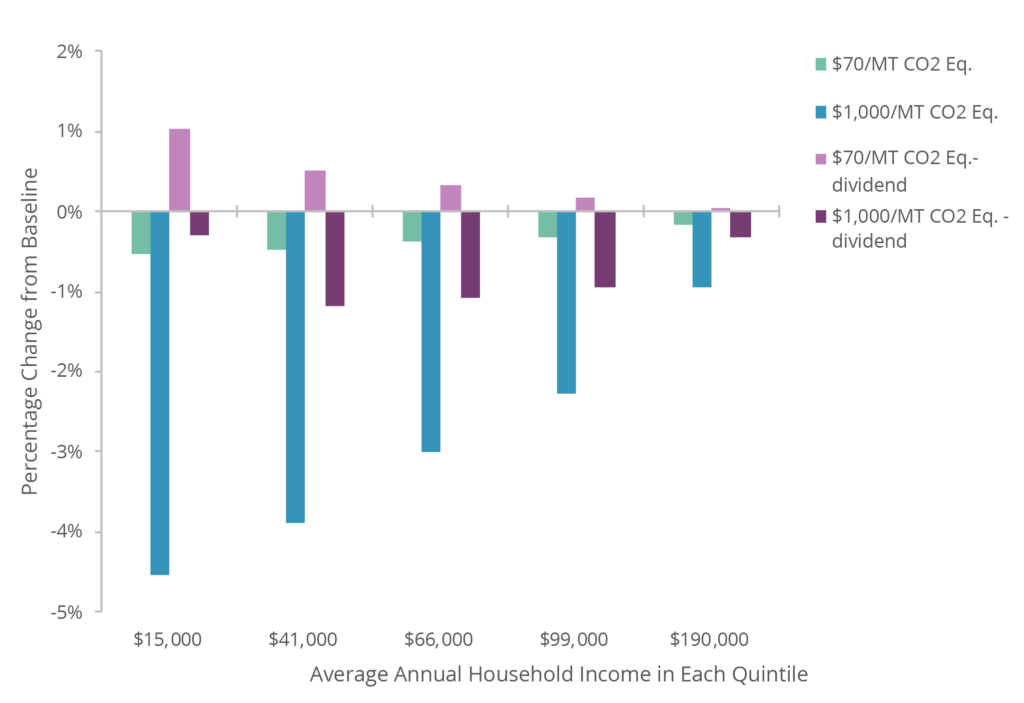

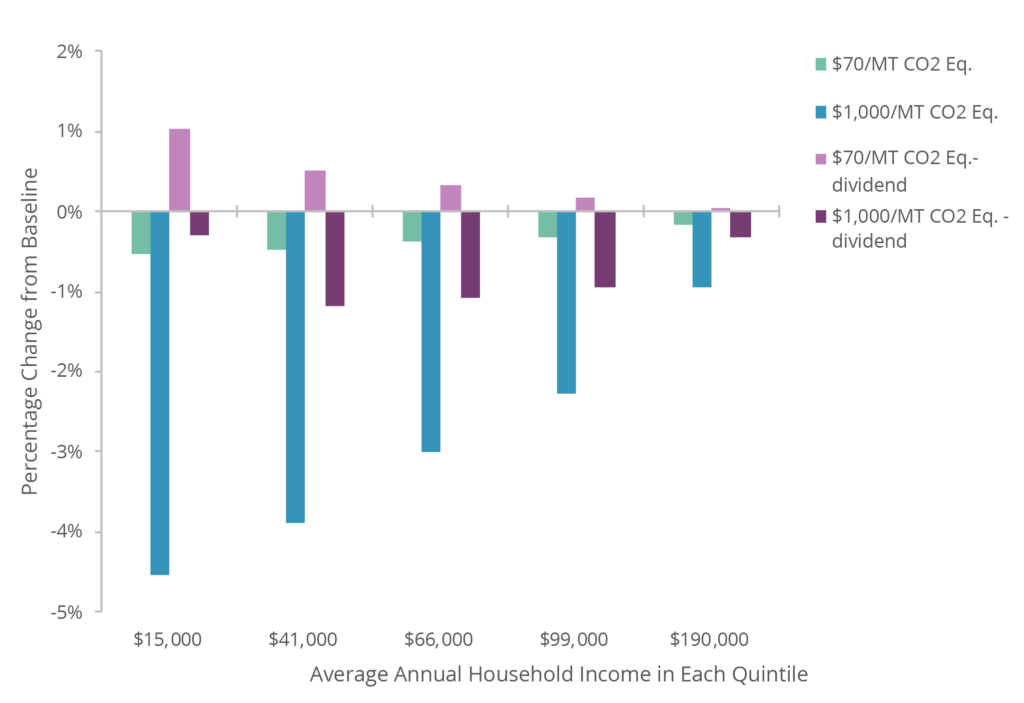

To understand the impact of the tax on a range of households earning different incomes, we divide households into five income groupings. More specifically, by average income quintiles ranging from the lowest 20% of household income groups to the highest 20%. A major finding of our report is that if revenues from a carbon tax set at the SCC are returned to Hawai‘i’s households in equal shares, lower-income households would be proportionately better off and households in every income quintile would experience a welfare improvement. There are two reasons supporting this finding. The first is that higher-income households demand far more GHG-intensive goods and services than lower-income households and therefore generate a larger share of the carbon tax revenue. This means that equal redistribution of revenues across households will disproportionately benefit lower-income households that produce fewer GHGs. The second reason is that visitors would pay the carbon tax while on a Hawai‘i vacation and all of the visitor-generated tax revenues are transferred to Hawai‘i households. [Our study assumes that carbon tax revenues generated from domestic jet fuel are kept for government spending, per the current use of the stateʻs jet fuel tax. Whether a carbon tax of this magnitude on jet fuel would be allowable under the constitution’s commerce clause or federal anti-head tax act is a legal question that merits further inquiry.]

On the other hand, at the higher carbon tax, the decline in Hawai‘i output and income outweighs the positive effects of redistribution of carbon tax revenue and eventually leads to declines in overall welfare across all income groups. Figure 3 shows relative changes in household welfare by income quintile for both the SCC and high carbon tax prices as well as when revenues are redistributed to households (“dividend”) or added to government spending.

Making lower-income households economically better-off in the transition to a low carbon economy is certainly a good outcome and helps to overcome concerns by policy-makers and the general public that a carbon tax would hurt this group. But a carbon tax set at the federal SCC leaves Hawai‘i miles away from achieving the state’s net negative emissions goal, with almost 10 MMTCO2 Eq. left to abate in 2045. left to abate in 2045. Yet the high carbon tax scenario poses serious tradeoffs for resident welfare, which becomes particularly tricky to contextualize because GHGs are a global pollutant – meaning that benefits in GHG mitigation will only be realized if global GHG reduction is achieved. So what do these results mean for Hawai‘i regarding the use of carbon taxation as a GHG reduction tool?

By estimating the cost of GHG abatement for a range of carbon tax rates, there may be a sweet spot for a carbon price in Hawaiʻi. Certainly the SCC estimate falls into that category, but past $300-$400/MTCO2 Eq. there are rapidly increasing costs to GHG abatement. Bottom line, at the right price and if revenues are returned to households, a carbon tax is an effective and equitable way to reduce GHG emissions in Hawaiʻi. Sub-national climate action should be complementary to, rather than a substitute for, national approaches to addressing the climate crisis. However, action by Hawai‘i and other U.S. states can continue to pave the way to a more coherent federal approach.

Interagency Working Group on Social Cost of Greenhouse Gases. (2021). Technical Support Document: Social Cost of Carbon, Methane, (p. 48). United States Government.

IPCC. (2018). Global Warming of 1.5°C. [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, H.-O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J.B.R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M.I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, and T. Waterfield (eds.)]. (p. 264).