BLOG POSTS ARE PRELIMINARY MATERIALS CIRCULATED TO STIMULATE DISCUSSION AND CRITICAL COMMENT. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED ARE THOSE OF THE INDIVIDUAL AUTHORS. WHILE BLOG POSTS BENEFIT FROM ACTIVE UHERO DISCUSSION, THEY HAVE NOT UNDERGONE FORMAL ACADEMIC PEER REVIEW.

By Byron Gangnes

Like all countries, Japan was hit hard by COVID-19, and the economy has struggled to get back on track since. Some headwinds are familiar to Japan: the softness in foreign markets has hurt an economy for which exports remain an important source of growth. But the pandemic’s aftermath also brought very unfamiliar conditions, in particular renewed inflation in a country that averaged less than 0.2% inflation between 1995 and 2019.

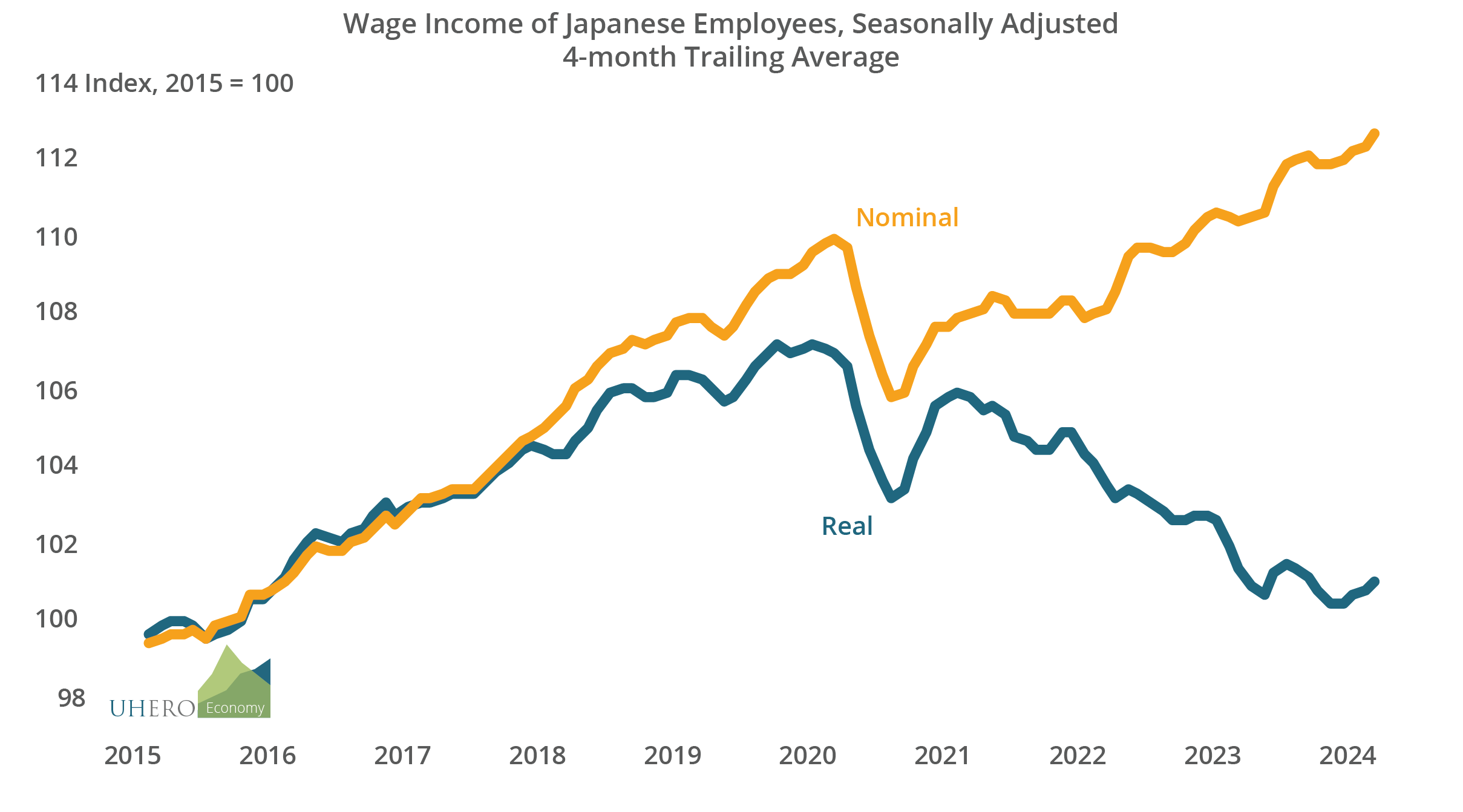

As consumer prices surged from zero to more than 4% during 2021-2023, real wages declined sharply, falling by more than 6% before stabilizing recently. As a result, consumer spending has contracted for the past four quarters, pulling down overall GDP. Following a flat fourth quarter, output fell at a 2% annual rate in the first quarter of this year, according to the first preliminary estimate.

Trade has also weighed on Japanese growth. Through much of 2022 and 2023, exports to China and the rest of Asia were particularly weak, reflecting China’s economic struggles and their regional impacts, even as exports to the rich developed regions were expanding at a healthy pace. But exports to all markets were soft during the past fall. A pick-up of exports since the end of last year looked to be a promising sign for manufacturers, but real exports fell for the first quarter as a whole, in part because of a safety-related shutdown at the small automaker Daihatsu.

Despite macroeconomic weakness, concerns about renewed inflation led the Bank of Japan (BOJ) to begin to move away from the extraordinary period of zero interest rates and longer-term rate (yield curve) control. But its moves are expected to be limited and will have to take into account any further weakness in the economy.

While a higher-rate policy might be expected to support a stronger yen, the BOJ’s announced policy change has not halted a decline in the currency, which in nominal terms is now lower against a trade-weighted basket of currencies than at the start of the floating rate period in 1973. This is a bit misleading, since adjusted for differences in inflation rates over time, the real effective exchange rate has not fallen quite as far. Still, as the yen has approached the 160 yen/US dollar level there are indications that the government has intervened to support the currency. A weak yen will continue to weigh on Japanese travel and domestic purchasing power, even if it supports the demand for Japanese goods and services.

It appears that consumer spending has not yet turned the corner. The three-month trailing average of inflation-adjusted retail sales was slightly positive in March. But, as we noted above, real consumer spending continued to decline in the first quarter. Forward-looking indicators are more encouraging. Consumer confidence has been generally on the rise for about a year now, and optimism about employment, household assets, and income growth are back to roughly their levels in 2018.

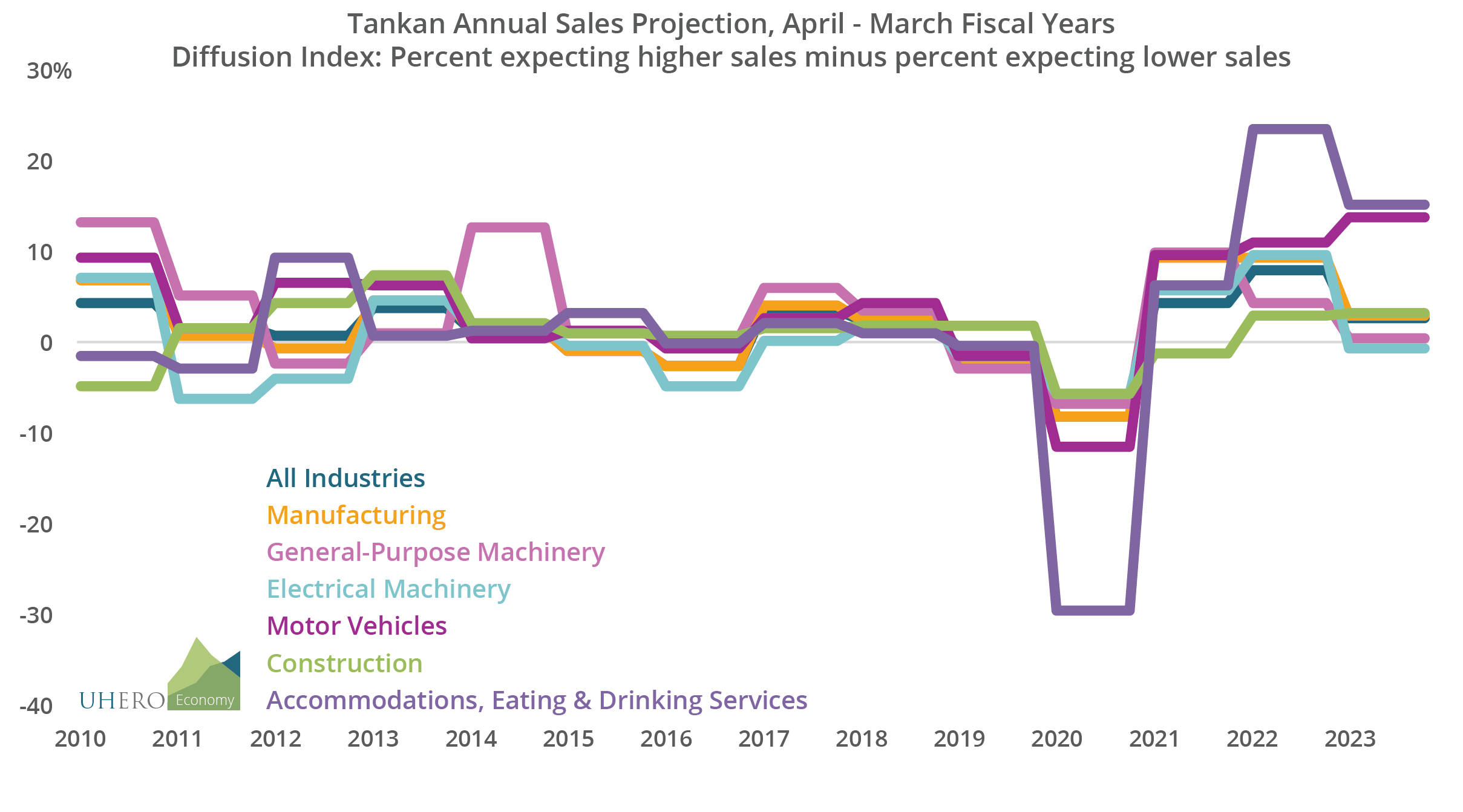

Businesses are somewhat less optimistic. From the Bank of Japan’s Tankan Survey, firms’ overall assessment of business conditions has improved. But, after a better year for sales in 2023, fewer firms are expecting net sales growth in 2024. A notable exception is the motor vehicle sector, where more companies expect stronger sales this year than last.

Fundamentals should also begin to turn positive. This year will see a substantial increase in worker compensation. In March, the country’s largest union won a 5.3% wage increase from Japan’s biggest companies. Pay gains will likely be smaller at the more numerous non-union enterprises. Overall, this year’s pay hikes should result in a return to modestly positive real wage growth for Japanese workers. That will help to fuel an uptick in consumer spending and economic activity as the year proceeds.

At UHERO, our outlook is for annualized quarterly Japanese growth to pick up to the roughly 1-1.5% range this year. Partly because of weakness in the second half of last year, annual growth for 2024 as a whole will come in at 0.8%, firming only slightly to 0.9% in 2025.

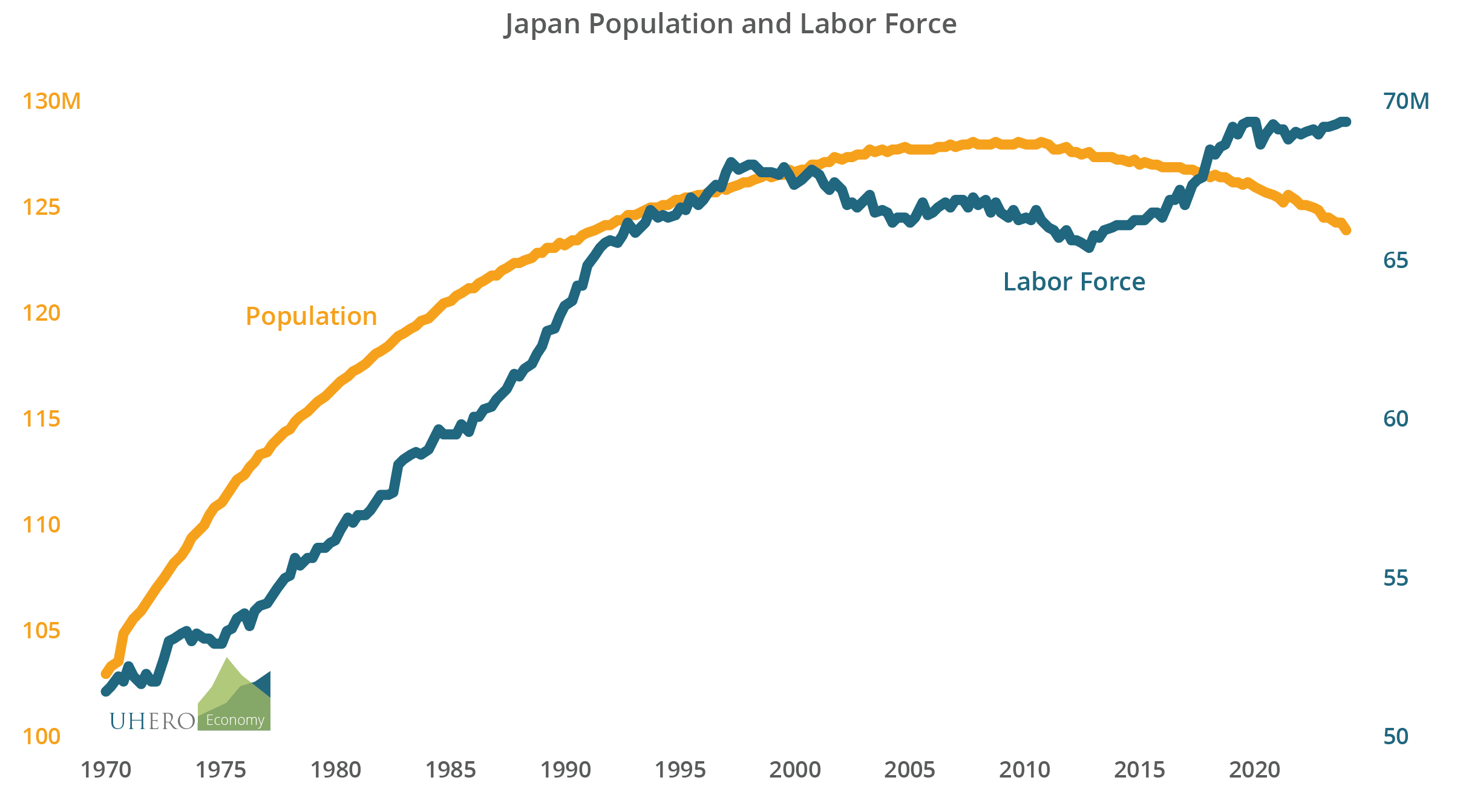

Growth in the 1% range is about the best we can expect for Japan in the near term, and the economy will decelerate further as we move into the second half of the decade. The slower growth trend reflects an anticipated decline in the country’s labor force, which has been delayed so far by an impressive and unexpected surge in the labor force participation of women, which has risen from 49% in 2013 to 55% last year. This has allowed the country’s labor force to grow even as the overall population shrinks.

With Japan’s labor force composition now approaching that of other rich countries and the old getting older, a falloff in available labor appears inevitable. This will hold down growth well into the future.