BLOG POSTS ARE PRELIMINARY MATERIALS CIRCULATED TO STIMULATE DISCUSSION AND CRITICAL COMMENT. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED ARE THOSE OF THE INDIVIDUAL AUTHORS. WHILE BLOG POSTS BENEFIT FROM ACTIVE UHERO DISCUSSION, THEY HAVE NOT UNDERGONE FORMAL ACADEMIC PEER REVIEW.

By Byron Gangnes

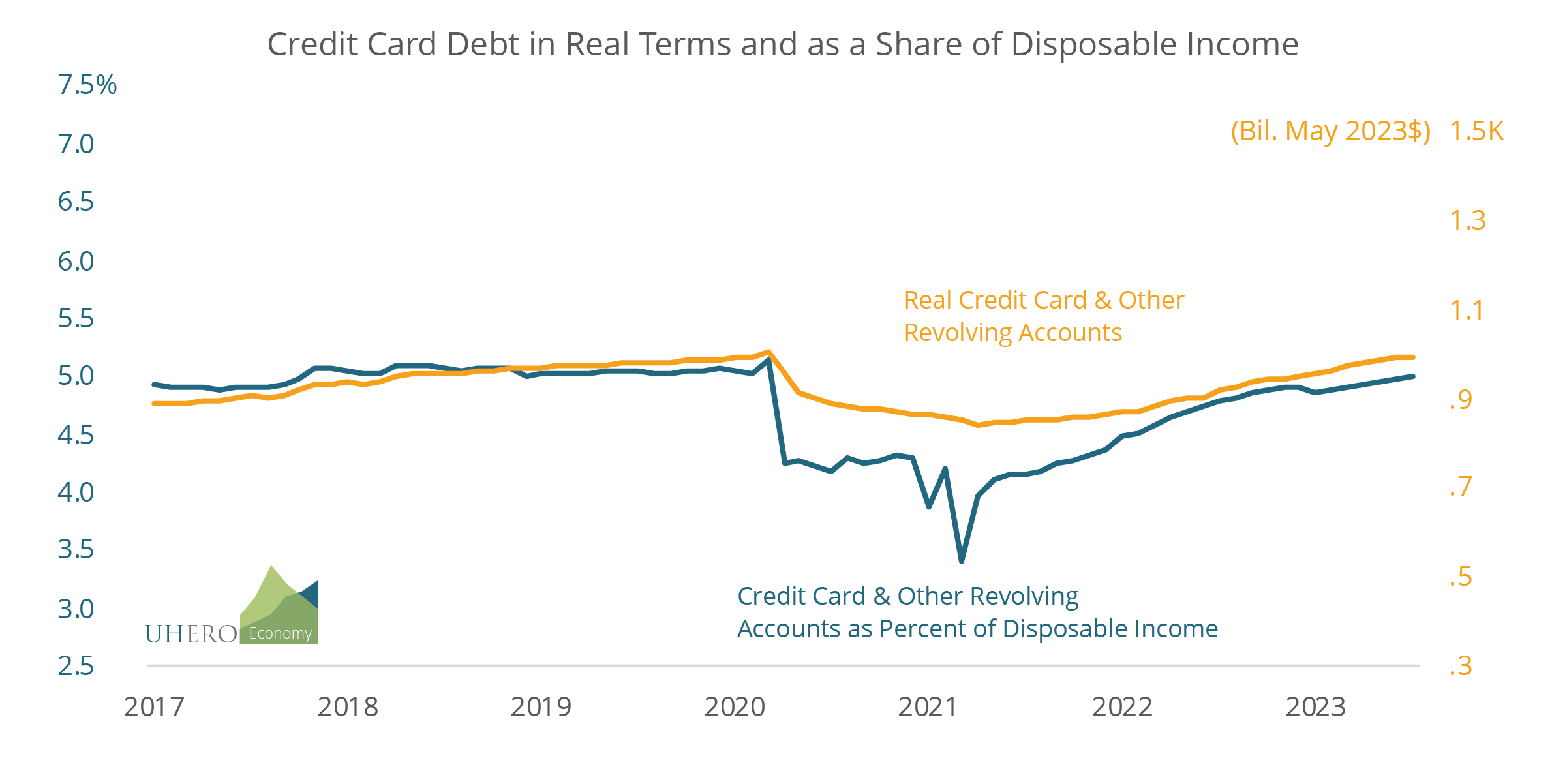

Credit card balances broke the $1 trillion mark recently, but their share of disposable income remains moderate by historical standards. And as the figure below also shows, they have risen only to pre-pandemic levels when expressed in real (inflation-adjusted) terms. There’s no debt binge out there.

But interest rates have risen considerably during the Fed’s current tightening cycle. How much has that changed the cost of financing credit card debt?

Source: Federal Reserve Board Form G-19 data, Fred database, and author’s calculations.

Average interest rates on credit card balances have soared over the past several years, rising from less than 16% in May 2020 to more than 22% in May 2023. And, of course, interest rates on credit card balances are the highest of any type of consumer loan.

There are only a limited number of quality articles on this issue, even if there are lots of short pieces on financial web sites. For this post, I have referred in part to a Brookings Institution article, Revolving debt’s challenge to financial health and one way to help consumers pay it off, by Jennifer Tescher and Corey Stone, and to the most recent Federal Reserve System periodic report, Changes in U.S. Family Finances from 2016 to 2019: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances.

According to the Fed survey, in 2019 a majority of families reported using credit cards “for convenience only.” In other words, they used their cards solely to make transactions and did not carry over any balances from month-to-month. We are interested in the remaining roughly 45-56% (depending on data source): those families who reported a credit card balance after their last payment. Estimates of the typical size of these rollover credit card balances vary surprisingly widely. In the Fed survey mentioned above, the median family reported owing $2,700 in 2019 and the average family $6,270, although Tescher and Stone note that these self-reported figures are likely understated. Information from banking and financial sources indicate much higher balances. As examples, the WalletHub Credit Card Debt Study found an average household credit card debt balances of $10,170 for the second quarter of 2023. The Ascent from Motley fool reports $5,910 of credit card debt for the “Average American” in 2022. It is unclear whether this refers to an individual or household. Forbes cites Transunion data that show an average credit card balance per consumer, of $5,733 in Q1 2023. Numbers for household rollover balances in the range of $10,000 per household are close to what available macro data suggest.

Unsurprisingly, credit card balances are higher for upper-income families but are much larger relative to income for families at the lower end of the income distribution. And according to a report from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), a much smaller percentage of households with low credit scores pay off their balances in a given month.

The CFPB estimates that this cost American families $120 billion annually between 2018 and 2020, easing to $117 billion by 2020 as households cut back on spending and used some federal pandemic assistance to pay down credit card debt.

What does this mean for the average family? To assess this, I accessed historical data from the Federal Reserve Board’s report, Consumer Credit – G.19 (ya gotta love those catchy Fed report names) on monthly balances for “credit cards and other revolving plans at all commercial banks”, as well as monthly interest rates charged to those borrowers who carry over balances. Now there are two difficult things to estimate:

(1) What proportion of households roll over balances, and

(2) What proportion of total credit card balances are rolled over.

Estimates of both are all over the place. To come up with a conservative estimate of credit card financing costs, I pick the largest credible share of rollover households that I found, 56%, and the smallest proportion of total credit card balances that are rolled over, 77%.

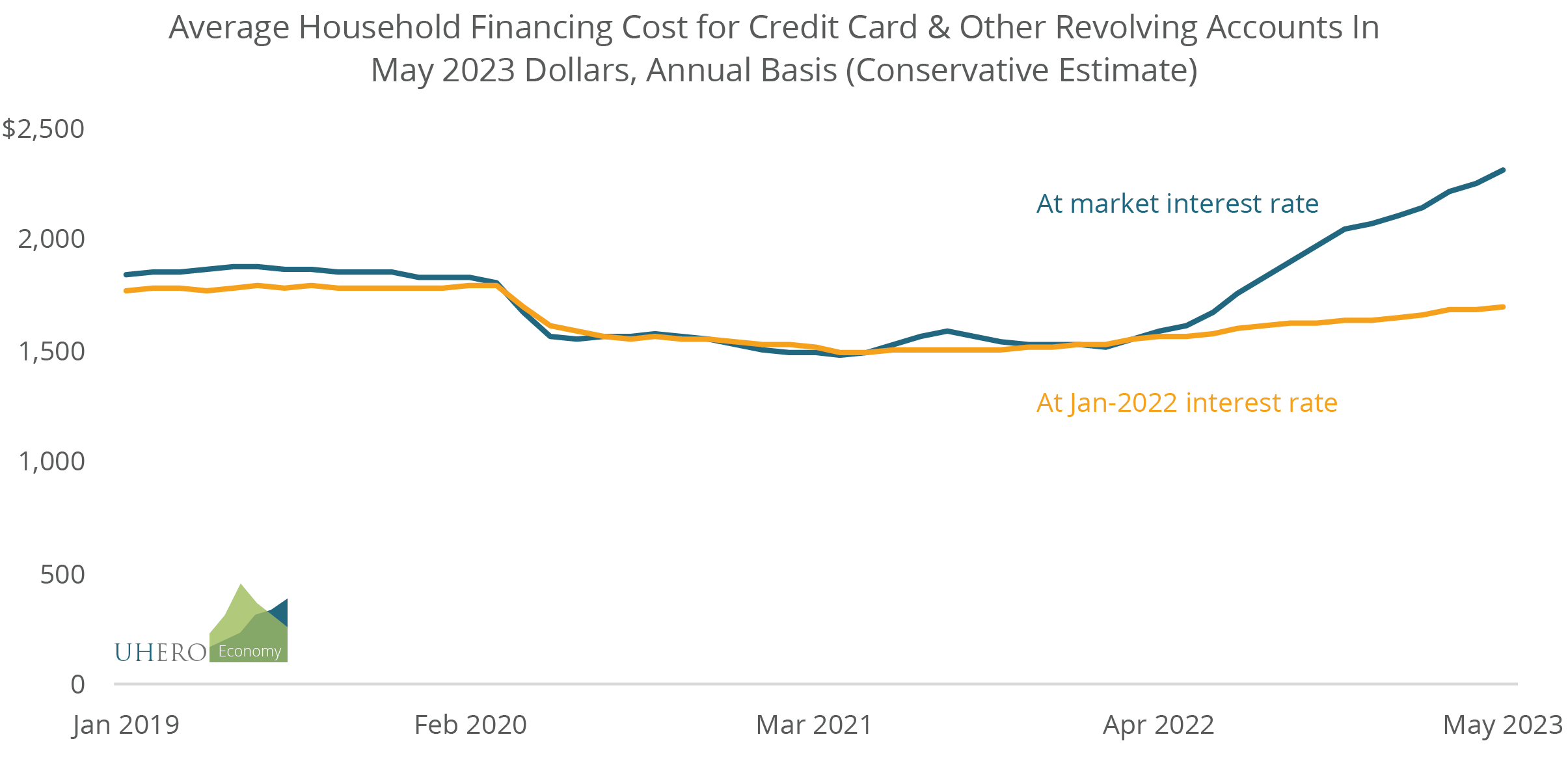

Based on these figures, I find that as of May 2023, households who rolled over balances were paying an average of more than $2,300 annually on an average credit card balance of about $10,400. This is up from annual credit card financing costs of about $1,525 at the beginning of last year. (All figures are in inflation-adjusted May 2023 dollars.)

Source: Federal Reserve Board Form G-19 data, Fred database, and author’s calculations.

If these numbers sound high, remember that these are averages across households of all income levels. Above, we observed that median household balances tend to be less than half that of the average household balance. So a “typical” family’s financing costs would likely be lower. And families of modest means would have even lower balances and financing costs, although they probably represent a larger share of income for those families.

In part, the higher credit card financing costs are the result of increased credit card borrowing over the past several years, even if overall balances are just now getting back to pre-pandemic levels in real terms.

But the second figure shows that an overwhelming share of the increased cost of carrying credit card balances is due to rising interest rates. The figure compares the evolution of actual financing costs at market interest rates with what those costs would be if interest rates were constant over time at their January 2022 level (16.26%).

The chart shows that if credit card interest rates were unchanged at their January 2022 level, the cost of carrying credit card balances would actually be lower today than before the pandemic, after adjusting for inflation. Looking just at the period since the beginning of last year, rising rates have raised the average annual interest cost for those households who carry balances by $615, more than three-quarters of the approximately $784 additional interest cost over that time period.

Again, keep in mind that this is an average rise in interest costs across all balance holders, and that a “typical” family’s financing costs may have risen by much less than $784. At the same time, recall that I chose conservative assumptions to come up with this $784 average increase in interest cost. If I were to take the less conservative estimates that 93% of balances are rolled over and held by only 45% of households, interest financing cost for an average household would have soared by $1,180 since the beginning of last year. They would be paying a total of $3,470 in annual interest.

If there is a credit card problem, then, it has much more to do with surging interest rates than it does with increased household credit card borrowing. Of course, from the standpoint of credit card debt burdens on households, that makes little difference.

Banking regulations allow issuers to set various rules for how they set the monthly minimum payment, but a household will generally have to pay either a fixed percent of their current balance (often 2%), or the previous month’s accrued interest plus a fraction of their outstanding balance. For example, one Capital One credit card charges 1% of the balance plus new interest on that balance and any late payment fees or past due amounts. The basic point here, is that higher interest rates and rising balances can both increase the out-of-pocket financing costs that credit card borrowers face.

In part, this may explain the recent rise in credit card delinquency rates, which have risen from 1.6% in the fourth quarter of 2021 to 2.8% in the second quarter of this year.

Oh, in case you’re wondering, the recommendation of Tescher and Stone for how to address the problem of high credit card financing costs is to require much larger minimum monthly payments than are currently implemented. That would substantially lower the total interest paid on credit card balances over time.

Thanks to Peter Fuleky for some helpful comments and error-catching.