BLOG POSTS ARE PRELIMINARY MATERIALS CIRCULATED TO STIMULATE DISCUSSION AND CRITICAL COMMENT. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED ARE THOSE OF THE INDIVIDUAL AUTHORS. WHILE BLOG POSTS BENEFIT FROM ACTIVE UHERO DISCUSSION, THEY HAVE NOT UNDERGONE FORMAL ACADEMIC PEER REVIEW.

By Leah Bremer, Zoe Hastings, Maile Wong, and Tamara Ticktin

Puʻulani (heavenly ridge) sits above the loʻi kalo (taro patches) that Kākoʻo ʻŌiwi, a community-based organization in Heʻeia, Oʻahu, has been actively restoring since 2010. Just five years ago, in 2018, 100% of the trees at Puʻulani were non-native species. Since then, a partnership between Kākoʻo ʻŌiwi and our interdisciplinary research team1 has worked with thousands of community members to transition Puʻulani to a biodiverse and culturally valuable agroforest that provides materials for lei, food, and, most importantly, provides opportunities for the community to access and connect with the forest.

University of Hawaiʻi Puʻulani research team in front of a native Loulu (Prichardia spp.). From left to right: Angel Melone (Masters of Environmental Management, NREM/UHERO/Heʻeia NERR 2020); Maile Wong (Undergraduate researcher and Field Manager, School of Life Sciences/ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi/WRRC/Sea Grant); Leah Bremer (UHERO/WRRC); Zoe Hastings (PhD Botany, School of Life Sciences, 2021); Matthew Kahoʻohanohano (PhD student, School of Life Sciences/Heʻeia NERR); Tressa Hoppe (PhD student, School of Life Sciences/Sea Grant/WRRC). Missing: Tamara Ticktin (School of Life Sciences). Photo: Leah Bremer.

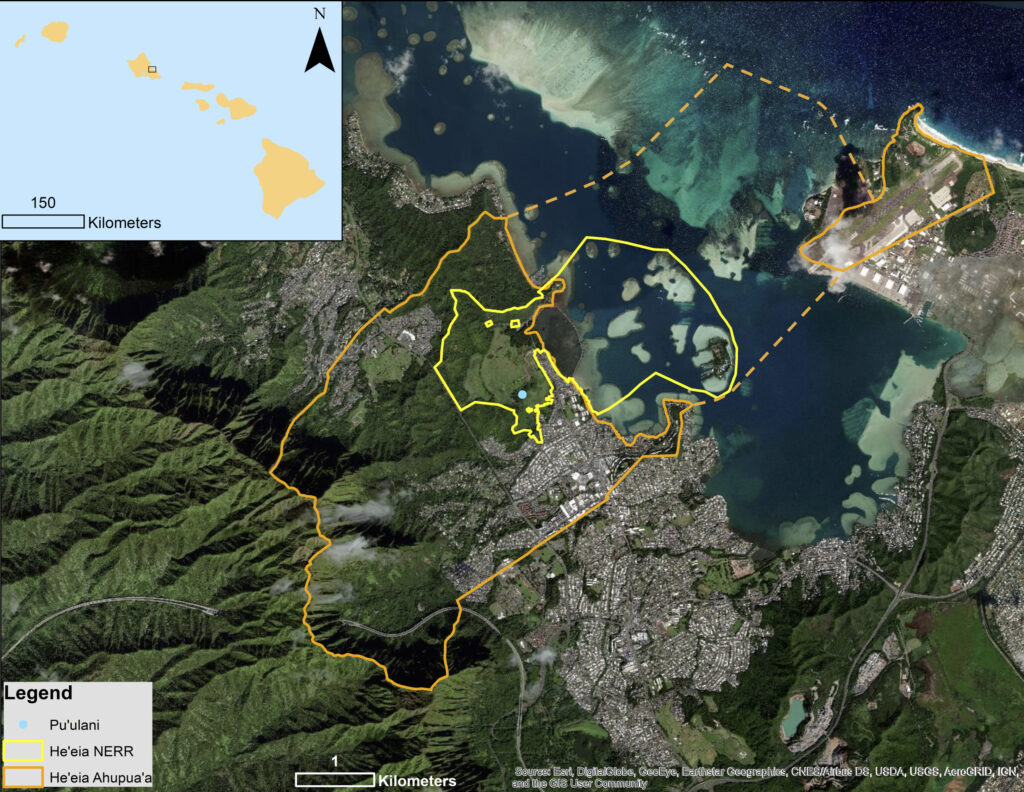

Location of the Puʻulani restoration site within Kākoʻo ʻŌiwi, Heʻeia, Oʻahu. Source: Melone et al. 2021.

Left: Tamara Ticktin and Tressa Hoppe help to net Loulu to protect them from the Coconut Rhinosorus Beetle. Photo: Leah Bremer. Right: Native wilwili (Erythrina sandwicensis) flowering for the first time in August 2022. Wiliwili were planted in front of all research plots, as moʻolelo tell that wiliwili capture unwanted energy and provide protection. Wiliwili wood was also used to make surfboards and ʻama for canoes. Photo: Maile Wong.

Agroforestry systems integrate trees and shrubs with other tended and harvested plant and animal species, and are known to provide a suite of benefits, including food production, erosion control, carbon storage, and biodiversity. They also provide important climate resilience benefits, including the ability to survive periods of drought and flood events. Importantly, Indigenous agroforestry was widespread in Hawai‘i prior to European colonization. While many of these systems went into decline with colonization, there is great interest in their restoration today.

Kākoʻo ʻŌiwi’s mission is to perpetuate the spiritual and cultural practices of Native Hawaiians, and agroforestry is an important part of their strategic plan for restoration of the nearly 200 acres of upland area now dominated by non-native forest. Puʻulani is the highest point that is easily accessible to the staff and community at Kākoʻo ʻŌiwi, and so it was selected as an ideal place to carry out the first agroforestry restoration effort. The participatory biocultural restoration is set up as an opportunity to learn and use lessons learned to inform future restoration across the other upland areas that Kākoʻo ʻŌiwi stewards.

Mahealani Botelho (Conservation Specialist with Kākoʻo ʻŌiwi) and Maile Wong talk story about Puʻulani at a community work day. Photo: Leah Bremer.

When we began the restoration, Puʻulani was covered with non-native trees, mostly Java plum, Fiddlewood, and Octopus tree, which are typical of non-native forests across low elevation lands in Hawaiʻi. It is estimated that approximately 40% of agricultural lands in Hawaiʻi are un-managed, and a similar percentage of conservation lands are considered low-priority and non-native dominant. Accordingly, the project at Puʻulani has important potential to inform restoration beyond Kākoʻo ʻŌiwi and Heʻeia.

Of course, Puʻulani has a long history far beyond this project. Prior to 1778, Puʻulani was covered in Indigenous agroforest and native forests. It was then was used for cattle grazing, and since then non-native trees and other plants have moved in. In Fall 2018, we selectively cleared the non-native forest on the eastern face of Puʻulani. In a huge community effort in 2019, we planted over 2,000 culturally valuable and useful plants of 25 species. We selected plants for the first round of planting that feed people spiritually and intellectually: lei plants, plants used in lāʻau lapaʻau (traditional Hawaiian medicine), and ceremonial plants. All but three of the original plants are native; the others are non-native and non-invasive plants with important uses to the community. Here is a full list of species and their uses.

Top: Puʻulani team members share some of the first harvests of ʻulu (breadfruit), limes, and banana. Photo: Josh Silva. Left: Maile Wong helps keiki harvest ʻolena at a Puʻulani workday with Kaiser Permanente. Photo: Zoe Hastings. Right: Zoe Hastings wearing a koa lei made by Maile Wong from Puʻulani.

Research carried out at Puʻulani broadly aims to understand how different metrics of restoration success change over the transition from non-native forest to culturally important agroforest. We are currently tracking changes in 1) soil health and microbes, 2) the capacity of agroforests to sequester carbon above-ground and in the soil, 3) growth, survival, and understory cover of the plants, and 4) community members’ connection to the site. Research is evolving and new projects will continue to help us understand best practices and benefits for implementing restoration through agroforestry. Additional information can be found on the participatory design, carbon storage, and current ecological results.

Top: Maile Wong measures a newly planted maiʻa iholena lele (Hawaiian variety of banana) in March 2019. Photo: Leah Bremer. Left: Tressa Hoppe harvests ʻiholena lele in 2023. Photo: Zoe Hastings. Right: Angel Melone assessed the amount of carbon stored in Puʻulani soils to 1-meter. This pre-restoration baseline will be compared to 5-years post restoration in 2023. Photo: Leah Bremer.

Prior to 2018, our interdisciplinary research team collaborated with Kākoʻo ʻŌiwi to understand the suite of cultural, ecological, and economic benefits provided by their current and future loʻi restoration efforts. See our findings in a publication that is part of a special issue on biocultural restoration in Hawaiʻi. Our research was also featured in two award winning episodes of Sea Grant’s Voice of the Sea: “The hidden benefits of farming kalo” and on the “Water Resources Research.”

For more information or to visit and/or volunteer at Puʻulani, contact Leah Bremer (UHERO/WRRC, lbremer@hawaii.edu), Zoe Hastings (School of Life Sciences, zchastin@hawaii.edu), Tamara Ticktin (School of Life Sciences, ticktin@hawaii.edu), or Maile Wong (School of Life Sciences, mailekw@hawaii.edu). Check Kākoʻo ʻŌiwi volunteer opportunities for work days.

Mahalo to our funders, including the Natural Resources Conservation Service, the Social Science Research Institute, the University of Hawaiʻi Sea Grant College Program, the National Science Foundation, the Heʻeia NERR, and the Kaʻulunani program (DOFAW).

Mahalo nui to our partners Kākoʻo ʻŌiwi and the Heʻeia NERR and to the many volunteers who make Puʻulani thrive.

Puʻulani community work days. Photos: Leah Bremer.

Regular Puʻulani volunteers Maya Walton and Katy Hinzen transplant bananas while social distancing. Photo: Leah Bremer.

Footnotes

1 Our research team includes the University of Hawaiʻi Economic Research Organization, the Water Resources Research Center, the School of Life Sciences, the Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Management, the Pacific Biosciences Research Center, the University of Hawaiʻi Sea Grant College Program.