BLOG POSTS ARE PRELIMINARY MATERIALS CIRCULATED TO STIMULATE DISCUSSION AND CRITICAL COMMENT. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED ARE THOSE OF THE INDIVIDUAL AUTHORS. WHILE BLOG POSTS BENEFIT FROM ACTIVE UHERO DISCUSSION, THEY HAVE NOT UNDERGONE FORMAL ACADEMIC PEER REVIEW.

By Rachel Inafuku and Justin Tyndall

Of the state’s 565,000 total housing units, 30,000 are listed as Short-term Vacation Rentals (STRs), meaning roughly 5% of local housing units operate as tourist accommodations. In a tight housing market with high prices and barriers to creating new supply, removing supply from the long-term housing market could harm residents by raising housing costs. However, we don’t know exactly how much STRs impact rents and home prices.

The founding of Airbnb in 2008 made it possible to convert housing stock into visitor accommodations with minimal effort and cost. In subsequent years, many other online platforms began offering similar services to facilitate STRs. The impact of these services on the housing market has been a topic of concern for many cities, particularly tourist destinations with high housing costs. With the highest housing costs in the nation, Hawaii fits that description.

To track the use of STRs in Hawaii, the Hawaii Tourism Authority (HTA) commissioned the collection of data on all major STR providers in the state. As shown in the maps below, STRs have a significant presence in almost every neighborhood in the state, despite being prohibited in several jurisdictions. The maps display STRs available for at least one night during February of 2023, as a share of the area’s total housing stock. While STRs are present almost everywhere, STRs have a much higher concentration in tourist centers, such as Waikiki and West Maui.

The maps display data by census tract. The color of each tract shows the number of STR platform listings in February of 2023 divided by the number of local housing units according to the 2021 American Community Survey.

The current prevalence of STRs has been fairly constant since 2019, as shown in the graph below. In the summer of 2019, Oahu increased penalties for operating an STR outside of designated resort zones, which resulted in a notable dip in listings. Despite evolving STR policies across counties, the stock of operating STRs in the state remains high.

The total number of STR listings over time are shown.

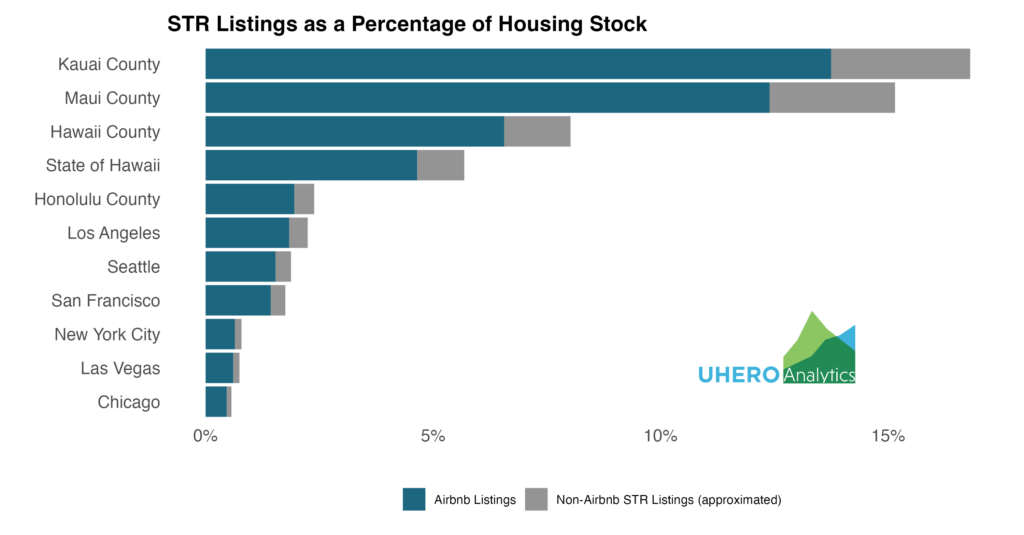

Comparing STR prevalence in Hawaii to other jurisdictions can give an idea of the scope of the issue. While we do not have national data across all STR platforms, we do have national data on Airbnb listings specifically. In Hawaii, 82% of STRs are posted on Airbnb (although many are cross-posted on other platforms, which we control for to avoid double counting).

Comparing Airbnb listings specifically can therefore provide a useful point of comparison. US cities that have been particularly concerned with the rise of STRs include San Francisco, where 1.4% of housing units are Airbnbs, New York City (0.6%), and Las Vegas (0.6%). In Hawaii, the situation is relatively extreme. The share of the state’s housing stock posted on Airbnb is 4.7%, more than three times higher than San Francisco and more than seven times higher than New York City. On the Neighbor Islands, the rates are higher still. Maui County has 12% of all housing units listed on Airbnb and on Kauai the figure is 14%. In the graph below, we provide an estimate of the full STR counts across jurisdictions by assuming that Airbnb’s market share in other cities is the same as it is within Hawaii.

Because STRs in Hawaii comprise a large share of total housing, especially in certain areas, STRs have the potential to wield significant influence on local rents and home prices. Each STR represents a housing unit that could otherwise be part of the local supply of permanent housing, exacerbating the state’s current housing shortage. While many factors contribute to high housing costs, the economic logic linking STRs to increases in the cost of housing is fairly unequivocal: diverting units from the pool of long-term housing reduces long-term housing supply and pushes up rents and home prices. The direction of the price effect is clear, it is the size of the impact that is difficult to estimate.

Supply and Demand Graph of Housing

Using findings from peer-reviewed studies that estimated the effects of STRs on home prices in other cities, we can estimate the likely housing cost impact of STRs in Hawaii. A Barcelona study comparing STR activity near and far from tourist attractions found that adding 50 STRs to a neighborhood increased rents by 2% and home prices by 5%, with larger effects in the most touristy areas. A study from Los Angeles looking at an STR policy change showed that reducing Airbnbs by 50% led to a 2% reduction in home prices and rents. A study of London found that a doubling of the Airbnb stock led to an 8% increase in rents.

By borrowing findings from the Los Angeles, Barcelona, and London studies, we provide estimates of the effect STRs have had on local rents and home prices on Oahu. The prevalence of STRs on Oahu (2.4% of housing units) is not dramatically different from that of LA (0.9%), Barcelona (2.6%), and London (3.0%), when those cities were studied. However, the share of STRs on the Neighbor Islands is significantly larger than in any of the study areas, making them much less comparable. Therefore, we only apply the estimates from prior studies to Honolulu County.

To estimate the effect of STRs on home prices and rents, we apply findings from the previous studies, but linearly scale their results to match the STR prevalence on Oahu. In the figures below, we estimate the level that median home prices and rents would be on Oahu if STRs were completely eliminated. This is a somewhat more extreme policy than has been considered. However, as of February, 73% of STR units on Oahu were operating outside of designated resort zones.

Looking at median home prices, estimates from the LA and Barcelona studies imply that, in the absence of all STRs, prices on Oahu would be 4-6% lower than they are currently. The median sale price across all housing units on Oahu (house or condominium) in 2022 was $860,000. Based on the estimated price effects from these studies, removing all STRs would push the median price down to the $810-$820,000 range. As for rents, there is a slightly wider range of estimates. The LA study implies that eliminating all STRs would decrease Oahu’s rents by 2%. Estimates from Barcelona suggest a 6% drop and estimates from London suggest an 8% drop. The median rent paid on Oahu is currently $1,880. According to prior studies, removing all STRs could lower the median monthly rent by anywhere from $35 to $160.

While Honolulu County’s STR prevalence is not dramatically different from the other study areas, other characteristics of Hawaii’s housing market are significantly different. Using the findings provided by prior research can provide only rough estimates of the possible magnitude of STRs’ impact on home prices and rents. The accuracy of estimates relies on the assumptions underlying the prior studies, as well as our assumption that the housing market on Oahu would behave comparably to changes in STRs.

The first bar shows the actual median home price on Oahu, the subsequent bars show an estimate of what home prices would be if all STRs were eliminated. The London study focussed only on rents rather than home prices and is therefore not shown.

The first bar shows the actual median monthly rent on Oahu, the subsequent bars show an estimate of what rents would be if all STRs were eliminated.

Whether the estimated price effects should be considered small or large is a matter of interpretation. If these price reductions were realized, Oahu would still suffer from extremely high home prices. Oahu’s median home price would still exceed the median price of any state in the US. However, the roughly 5% reduction in housing costs would represent a sizable improvement in the standard of living for renters and first-time home buyers, particularly lower-income residents for whom housing costs represent a large share of overall expenses.

There is evidence from other markets that STRs increase both home prices and rents. In Hawaii, STRs play a truly outsized role in the housing market compared to other locations. While far from a silver bullet to address the state’s housing shortage, the scale of the market suggests that changes to the regulatory environment around STRs would have significant consequences for the housing market.

The authors would like to thank India Alford for her valuable research assistance on this project.

Funded by the Coronavirus State Fiscal Recovery Fund: Data Infrastructure and Analysis for Health and Housing Program and Policy Design – Response to Systemic Economic and Health Challenges Exacerbated by COVID-19 (State of Hawai‘i award number 41895)

References

Koster, H. R., Van Ommeren, J., & Volkhausen, N. (2021). Short-term rentals and the housing market: Quasi-experimental evidence from Airbnb in Los Angeles. Journal of Urban Economics, 124, 103356.

Garcia-López, M. À., Jofre-Monseny, J., Martínez-Mazza, R., & Segú, M. (2020). Do short-term rental platforms affect housing markets? Evidence from Airbnb in Barcelona. Journal of Urban Economics, 119, 103278.

Shabrina, Z., Arcaute, E., & Batty, M. (2022). Airbnb and its potential impact on the London housing market. Urban Studies, 59(1), 197-221.

14 thoughts on “Short-term Vacation Rentals and Housing Costs in Hawaiʻi”

Please consider comparing Hawaii’s home prices and rental costs to other cities that allow prefab and mobile homes. Without mainland manufactured homes in our inventory, our state has almost no Cheap Homes. This affects Starter Homes for young people and the overall costs of housing and rentals. We have the shipping for mainland manufactured homes. We have the land for these homes. We need the county permits to allow quality mainland companies to manufacture homes for each island.

Informative post! I have bookmarked this link for future blogs.

Nice work again, Justin and Rachel. Three critiques worth a follow-up in further research. 1 Fixed flow-supply of new housing units must be assumed for the stock of housing to “shift to the left” as your animation depicts. But there is no economic reason why enlightened housing regulators, recognizing that financial innovation (hosting apps) reduce entry barriers (lodging supply) and reduce search-and/matching costs (lodging demand) and make habitation more substitutable across duration. Habitation length is a continuum, not binary [0, 1] visitor v resident. Hawaii could have built 5 percent of its housing stock–indeed for half a century before the mid-1970s Oahu’s incremental capital ratio (dK/K) was 4 percent. (Flow housing demand also is dynamic, not static, but in light of decades of growing resident net-outmigration is this cause or effect?) 2. AirDNA data for Kailua CDP on Oahu from May 2029 (pre-C&C crackdown) show distinctly makai spatial orientation of STRs. But makai-oriented houses are more expensive than mauka. The putative causality presumed by Pop Econ purveyors of NIMBY–“STRs increase housing cost”–suffers a ceteris paribus fail, and may be reversed. STRs may emerge in makai orientation BECAUSE they are the more expensive homes than mauka. Only investors who MAY securitize habitation into shorter-term intervals can afford them: the apps enable securitization. 3. Remote work (WFH, digital nomads, etc.) has changed the post-pandemic labor marketscape–an hysteresis. Census data show that at least 10 percent of Hawaii workers work from home full-time, twice pre-pandemic proportions–18 percent nationwide–while at least 10 percent in Hawaii do so part-time (hybrid) (both ACS data), and 20-25 percent of Hawaii respondents report working from home in the last 7 days (June 2022 through March 2023, with a RISING trend, in Census Household Pulse Surveys). Enlightened housing regulators might recognize that stifling latent productivity unleashed by severing work from location is not just socially inefficient (Oahu commute times decreased 10 percent and departure times from home for commutes shifted one-half to one hour later in the morning, on average, from remote work), but also would seem to violate the spirit of U.S. constitutional interstate commerce protections. Is Hawaii an outlier in STR shares or simply at the forefront of distributed work and the evolution of travel and tourism? Great blogpost, you two, and an inspiration for further investigation.

STR’s should be permitted and taxed same as hotels. Often STR’s disrupt owner occupied neighborhoods or HOA’s and cause increased maintenance, security monitoring, and disrupt the hospitality business.

The issue here is that the study begins with the premise that STR’s are causing higher rent prices, and then the study sets out to prove the hypothesis. And while , yes, decreased supply causes higher prices, this study does not look at the impact of decreased STR’s on the overall economy for Hawaii (such as fewer jobs in the tourism service sector, which may disproportionally impact the portion of the population who are renters), nor does it examine other alternative strategies which may lower rental prices, such as changes to the Landlord Tenant code which could make long term rentals more attractive to investors, and more efficient governmental systems for the approval of building market priced housing for the people who live and work in Hawaii. Most disturbing of all however, is how the goal of the study is to lower rent for people who live and work in Hawaii, instead of addressing how we can create a Hawaii where the people who live and work here can actually afford to own here.

Dead On!!!

If we only had one vacation rental unit on the whole island chain and it employed 10,000 people would shutting that unit down and returning it to local use ( thereby creating another local housing unit ) really improve housing affordability? Or would the effects of destroying 10,000 jobs outweigh the benefits of returning a single unit to local use? I think that question is pretty easy to answer.

What if those 10,000 jobs were spread over 10 units? Spread over 500 units? 1,000? Where is the balancing point between the number of units ( inventory ) and the number of jobs ( revenue )?

This article doesn’t even ask that question and certainly doesn’t answer it.

What it does do is prove that the affordability crisis is not being driven by vacation rentals. According to the study the elimination of homestay operations would only reduce prices by 2%. Median home prices have increased by 26% in the last 24 months ( during which time absentee vacation rentals were heavily regulated on all of the Islands ). Prices have more than doubled in the last ten years.

Vacation rentals are not the cause of the housing crisis. And eliminating them entirely would impact the livelihood of thousands of Hawaii families that service, manage and own vacation rentals – all for a measly 2% drop in prices ( roughly equivalent to the change in prices in a over a two month period ).

Eliminating an entire industry to offset two months of price gains will not solve the housing affordability problem and will, in fact, make it worse. It will destroy much needed income currently going to families who count on vacation rental dollars to pay their own mortgages. This makes their homes unaffordable to them.

I know it is easy to look at the housing market as a zero sum game, but it is only a zero sum game if local government makes it difficult or impossible to build new housing stock ( as it has done in every single county in Hawaii. )

The reality is that income from vacation rentals goes to local families who use those funds to pay for their own housing. The market is complicated. And studies like this one only cloud our discussions of the topic by creating the illusion of simplicity. Like most things in life, the real story is far more complicated.

In order to really understand the impact of vacation rentals it is important to examine a couple of other factors:

The impact to employees in the vacation rental industry. Cleaning crews in the vacation rental business are paid better than workers in colonial hotels – in some cases MUCH better. How would shutting down vacation rentals affect housing affordability and availability for these employees?

The impact to property owners who live in our local communities and count on vacation rental income to make ends meet.

The broader economic impact of taking vacation dollars that are currently going to local vacation rental owners ( who spend their money locally ) and redirecting it to colonial hotels who then export it to financial hubs like New York and Tokyo. Does sending visitor dollars to the mainland really improve housing affordability?

Until we understand the impact of the revenue on the economy it is simply impossible to really understand the impact of the inventory currently in use as homestays.

I look forward to seeing a real analysis of the impact of vacation rental units on housing affordability – this time taking into account how revenue from these operations benefits local families and the broader local economy.

Thank you Joshua. I totally agree. Another thing that wasn’t looked at is the increase in housing in places where people want to live. Many people have moved south and to more desirable places after the pandemic. People are working more from home and realizing life is short. Hawaii is finite (or it should be), let’s NOT overbuild and ruin it for everyone! STR’s bring in a lot of money to the community and to the homeowner who hosts. Some people couldn’t afford to live here without this extra income. Nobody wants people buying houses to rent out to short termers, but what’s the difference when the long term renters are coming from the mainland as well. WHO is actually a qualified Hawaiian citizen? We are encouraging more wealthy people to live here, while driving those who grew up here out. It’s kind of happening everywhere. Shutting down STR’s is not the answer. It’s a bigger issue. If you want to fix it, think outside the box. Don’t just blame the STR owners.

Another factor that was not addressed are the number of STR’s that are hosted rentals. Meaning the owner lives in part of the property and rents out the other part as an STR. For a number of our elderly this in the only way they make ends meet. As a Board Member of the Real Property Assessment Division, I hear cases of our elderly being affected this way constantly.

Please remember that STRs in Hawaii include rentals that are less than 180 days. This includes the entire temporary housing market. Eliminating STRs would greatly impact the following transient renters: traveling medical personnel, displaced residents (thousands per year based on various minor and major events), emergency workers, contractors and marginal renters who can only rent week-to-week or month-to-month. In areas like Waikiki, these renters make up 50% of some of the STR buildings. Regulation has stopped new STRs on most islands. This is not the case for hotel development which also takes up land and permitting time that could be used to expand our affordable housing stock. I believe it is time to stop blaming the housing crisis on STRs that are primarily owned and operated by residents who are also trying to afford to live in Hawaii.

I would like to second that this study is making several glaring mistakes especially as it applies to the Oahu market.

The term STR does not mean anything on Oahu — you will not find that term in the language of Oahu’s Land User Ordinance that became law in 1980s, you wont find it in Bill 89 that became law in 2019 nor in Bill 41 that was enacted last year

Oahu uses the term of TVUs — Transient Vacation Units which prior to Bill 41 meant properties that are legally allowed to be rented for less than 30 days and majority of them are in resort areas(With exception of few hundred Non-conformant Use Certificate that grandfathered few hundred properties in residential areas).

When this study states that Oahu currently has more than 8000 STRs, do they actually mean a very limited supply of TVUs or do they include properties that do 30+ days rentals which used to be allowed everywhere on the island until Bill 41 changed the definition of what is currently legal and was quickly challenged in Federal Court?

The study states that it got its data from insideairbnb.com which is not an organization I heard about before, but most importantly they do not state how they collect their data and their methodologies. Regardless, i went to their site at http://insideairbnb.com/hawaii and used their tools to only show:

* The county of Honolulu

* only “short term rentals” — with minimum stay of less than 30 days

* Recent ones(with review in the last 6 months) — removing stale or orphaned listings

* Frequently Booked(properties that are booked for more than 60 days out of a year)

Low and behold — Their tool only showed 2863 Short term rentals in the county of Honolulu, where according to Censuses American Community Survey there were 336,412 housing units.

In other words, rentals of less than 30 days constitute 0.85% of total housing units on the island.

Yes you read this, right — its less than 1% of total housing stock and about 1/3rd of the number that this study has stated.

It does not look like this study is fully baked and need someone to fact-check their numbers

Two thoughts on additional information missed in this report

1-If you look at the Hawaii Tourism Authority reports on ivnventory of STR’s from 2010, you will see that the inventory has barely moved as compared to the growth of population, that indicates no building which is the real issue.

2-If you dig into the economics of the STR’s stock of units, most are studio, 1 and 2 bedroom units, 400-900 sq feet, located on small parcels of land with no area for kids to play and on busy roads, have HOA dues of $15K to $30K a year, one parking spot, endless special assessments due to shoreline erosion and building maintenance requirements.

How is that affordable to the local community to live and pay? This inventory is NOT family friendly or affordable, dig into the real numbers (living expenses to rent or own) that will have impact on what is affordable housing.

I suggest adding in a look at the proportion of STVRs that are owned and operated by persons who live outside Hawaii, rather than being owned and operated by Hawaii residents. Looking around me in a Hawaii County community not far from large hotels and resorts, this proportion of “away” owner/operators seems large and getting larger. The “away” owners contract a realty company to manage on-island (if they follow Hawaii County STVR law). A realty company has a person or few persons to manage a caseload of many STVR units. The other direct personnel are cleaners who come in between occupancies. It takes few of those to serve a caseload of many units. I imagine STVRs are not adding a lot of direct employment in our community. Perhaps researchers could look at these questions as well.

This is a skewed report, absolutely! No hotels will invest in Lava Zone 1 & 2 on Big Island. The only option tourist have to experience East Hawaii is an STVR. There is NO LONGER a path towards an ‘unhosted’ STVR permit in Hawaii County. They are using this report to license and effectively eliminate hosted vacation rentals as the council IS AWARE that there is NO HOME INSURANCE for ‘mixed use’ properties. When directly asked at a community meeting, Heather Kimball basically answered, We dont care by giving a flippant response of, “well, we dont require owners are insured”

If we were to comply with her new rules, we would be cancelled by HPIA, our only home owners insurance option.

This will effectively drive more of Puna’s population into poverty and into social programs.

Eliminating one of the few paths to employment in East Hawaii is counter productive. Lets think, REALLY THINK